Hesperian Health Guides

Trauma

- a single incident, like a dog bite

- a horrific event affecting many people, like a mass shooting

- ongoing or past events, like growing up in a violent home

Trauma can make a person feel unsafe, insecure, helpless, and unable to trust the world or the people around them, either sometimes or all the time. Trauma recovery can take a long time. An old traumatic experience can still be a problem for someone, especially if they never had help healing. Trauma that happened to one’s parents or ancestors can also have lasting impact.

We may know survivors of trauma, even if it is not something they talk about or we are aware of. This includes adults affected by abuse or other childhood injuries, sometimes before they were old enough to understand (see “Violence in families”). A person may remember feeling terror without recalling details of what happened. Or people will remember the events but not remember the feeling of terror, which can make it harder for them to understand their continuing problems. Sometimes traumatic situations are still occurring, and people fear that talking about it could cause them or others further harm. Some people who experienced violence or abuse also were abusive toward others. This can lead to confusion, guilt, shame, anger, fear, and other painful feelings.

Contents

Common signs of trauma

Immediately after a traumatic event, people often experience shock and denial. Longer-term reactions include unpredictable emotions, flashbacks, strained relationships, avoiding people, and avoiding anything that reminds them of what happened. They may have depression and physical problems such as head or stomach aches, nausea, difficulty concentrating, nightmares or insomnia, hopelessness, and feeling like nothing matters. These reactions can be part of more lasting effects from trauma known as post-traumatic stress disorder (post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

People who have experienced trauma may be jumpy or constantly alert to danger, may feel irritated or angry, and may always have the trauma on their mind.

Reacting to trauma, the mind may try to protect itself by separating body, mind, and emotions, usually experienced all together. The person may remember feeling nothing during the traumatic event, or feel “like I was outside of myself watching it happen from a mile away.” The separation between feelings and body can become a habit. It can cause numbness as another reaction to trauma.

Support people who have experienced trauma

Ways to support people following trauma include:

Provide a sense of safety. People can have a hard time recovering their sense of safety even if the trauma is over. The body stays in the state of responding to danger, so the person doesn’t feel safe. Help them feel more comfortable. For instance, if they don’t feel safe talking with you in a room with the door closed, ask what would feel OK, like a bench in a quiet corner of a park where others are around.

Show you are trustworthy. When people have experienced trauma, they may be cautious with others, always on edge, and fearful of attack or betrayal. You can show you can be trusted by being predictable and by not hiding anything. For example, be on time, avoid promising something unrealistic, do exactly what you say you will do, and clearly explain why you are doing things and why you are asking certain questions.

Give a sense of control. In a traumatic situation, people experience a loss of control. Help people regain control by giving them choices, big and small. Have them decide if, when, and where they talk with you, participate in decision-making, and know what will happen next.

Take it seriously. People who have experienced trauma may feel isolated or out of sync with the rest of the world. Be aware of the conditions that continue to create danger and cause trauma in people’s lives, and show you take them seriously. By openly recognizing that racism, for example, targets people for violence or unequal treatment, you can demonstrate that your support is not dependent on them accepting the conditions that caused their trauma.

Group activities to help people living with trauma

For some people, connecting with others who have faced similar types of trauma can be helpful in feeling less alone with their experiences. (Chapter 8, "Support groups", includes ideas about how to set up and run support groups.) Here are some ideas for group activities.

When a trauma occurs, people often feel that it shouldn’t be talked about. They may feel shame, as if there was something wrong with them that brought it on, or that they are damaged or tainted by what happened. Sometimes they feel no one wants to hear about such a horrible thing, which increases their isolation.

Activity

Speak the unspeakable

Facilitating a support group for people who have experienced trauma can bring up a lot for the group and the facilitators. Talk with others who facilitate such groups to decide whether you have the resources and experience to take this on. When setting up a support group, provide clear information ahead of time about what to expect. That way, people can decide if they are ready to share some parts of what they are dealing with and to hear about other people’s traumatic experiences. Follow suggestions later in the book for starting support groups, including establishing group agreements of how information will be kept private and other ways to help people feel comfortable. If you know everyone feels ready to connect with others with similar experiences, introduce the idea of “the unspeakable.” Part of what makes a trauma a trauma is how alone people often feel, as though what happened makes them not belong, that no one could understand or wants to hear about it. For some people, writing, drawing, working with clay, or other forms of expression can work better than talking, so make art materials available during the group. Let people know they can share a drawing or something they’ve written instead of talking. Or they can pass if they aren’t ready.

- Start by inviting people to mention what can make it hard to talk about their experience. Examples include: “I don’t want to think about it,” “People don’t want to hear about this kind of thing,” “People look at you differently when they know this happened to you,” “It was worse than words can say.” Remind the group that it is OK to choose not to speak.

- Share the idea that part of feeling better after experiences like this is finding ways to connect with others—being seen and heard by others—rather than staying all alone with it. Ask the group to name the things that others can do to convey that they are listening/paying attention. Examples include: “Don’t look directly at me, but don’t act like you are ignoring me either,” “Take a moment to think before you respond.”

- Give people a set time (perhaps 5 minutes) to think about the experience that brings them into the group. You might say: “This group is for people who have experienced gun violence in our communities. Take 5 minutes to think, write, or draw on your own about your experience with gun violence.”

- Explain they can choose to talk, read out loud something they wrote, or show a drawing. Suggest they focus on a small piece because it is common when talking about trauma to get caught up and feel like it is happening all over again. Let the group know that there will be a time limit and each person will have the same amount of time to share. As always, people can pass if they don’t want to share.

- Invite people who feel ready to take turns sharing part of their experience, talk, read aloud something they wrote, or show a drawing. After a person has shared, with the group showing they have been listening, ask if they felt heard and how it felt to share before the next person begins. Remind people to avoid commenting on what others share.

- When everyone who wants to has shared, invite the group to reflect on what people are thinking or feeling after the sharing, or something they learned or appreciated about listening to others. Be clear that people are not being asked to talk about anyone’s specific experiences or to give advice.

Activities like these can bring up hard-to-manage feelings. Get group agreement at the beginning to support one another and have a plan to provide additional mental health support if needed. If you are co-facilitating with others, make time to debrief and support each other following a group meeting. If you are facilitating by yourself, plan how you will debrief after the meeting and have support.

Creating the more complete story

Traumatic events harm a person’s way of understanding the world. They might experience this as a spiritual crisis or the end of everything familiar: “Nothing makes sense anymore.” Someone who feels as if senseless, horrible things can happen at any time may question if life is worth living.

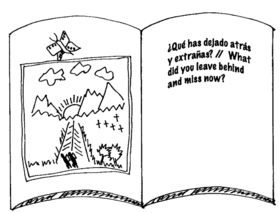

Creating a fuller story of what happened that puts it in the context of a person’s broader, complex life can be part of healing. This may include “speaking the unspeakable” as a first step It may also help to “tell a story” that makes the trauma just one part of a person’s life and remind them that their life includes a past, a present, and a future. A group can come together to create stories that provide connection and empowerment through artistic or documentary expression.

Digital stories. Voices to End FGM/C has connected with groups in the US and other countries to support survivors of female genital mutilation or cutting. They use storytelling and media production so survivors can tell their own stories on their own terms. The stories are made into short videos and used for social justice advocacy to prevent female genital cutting practices.

Creative storytelling. NAKA Dance Theater supports healing circles with immigrant domestic workers through theater, movement, textile art, collage, and other arts. One group produced a theater piece and a color zine to reflect on their experiences of forced migration, violence, and injustice in the workplace. The zine doubled as a journal for future participants by including questions for reflection and blank pages where people could write or draw their own stories.

Help resolve feelings of blame

One consequence of experiencing trauma is that people may feel betrayed by their loved ones (or others on whom they depended) for “letting” this happen to them, even if a part of them knows it is more complicated than that. Adults may feel let down by partners, government officials, or neighbors, and children may feel let down by caretakers who did not protect them. Adults, in turn, may feel shame for not having been able to protect a child or a spouse.

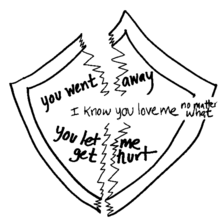

Helping people talk about these feelings or explore them through art can be important to healing, to making space for understanding that what happened was not their fault. It can also help people rebuild and strengthen their “protective shields”—the real abilities that we have to protect ourselves and others under ordinary, non-traumatic circumstances.

Activity

Repair the protective shield

This activity can be used to help someone while they think about the person they feel let them down. Or it can be done with the two people involved, such as a parent and child. Start by talking about how hard this activity can be and why it is important. Both sides are hard: feeling let down by a loved one and feeling that we failed someone we love. If you are doing this with a parent and child, help the parent anticipate that it can be hard to hear what the child expresses but that it is important to hear them out completely. Explain that this is part of an ongoing process, not something that can be healed quickly.

- Invite the person to draw a shield shape.

- Guide the person to talk about specific things that happened that made it feel like the shield was not working, for example, “You didn’t come when I called you,” “You left me alone,” “You didn’t stop the fire from burning down our house.” With each statement, make a rip or use scissors to make a cut in the shield.

- Invite them to look at the broken shield and talk about the thoughts or feelings that come up.

- Then invite them to list things that represent protection and patch the broken shield Use masking tape with words written on it or images cut out of magazines showing healing or protection. For example, write, “You come and hold me when I’m scared at night” or add a picture of a watchdog.

As you look at the broken/repaired shield together, invite them to talk about their thoughts and feelings.