Hesperian Health Guides

Grief and loss

HealthWiki > Promoting Community Mental Health > Chapter 2: Stresses affect mental health > Grief and loss

- the death or approaching death of someone close.

- the death of someone in the community or a respected person, whether or not there was a personal relationship.

- the end of a relationship, a divorce, loss of a job, being forced to move or losing a home, having a serious or ongoing illness, or adjusting to a disability.

- tragedies that affect many people at once, including violence, displacement, and disasters.

Although all of us will experience grief, different people will show and experience grief in many different ways. Grief has no single pattern or timeline. People in your family or community who have experienced the same loss may go through it very differently. Even after time has passed and it seems the hardest part is over, intense feelings may return. Ups and downs can continue for a long time. As feelings gradually ease, it becomes more possible to live with the loss as life moves on.

Contents

Support for grieving

After a loss, paying attention to your eating, exercise, and rest, and accepting support from others can help you get through the first weeks and months.

Spend time with others who are grieving the same loss or who can relate to yours. Planning or attending religious or other rituals for burial or remembering can bring people together as well as give them something specific to do when they may feel helpless in other ways. Support groups with participants who have had a similar kind of loss can provide a place to work through feelings. As with other situations involving strong feelings, many people find writing, music, art, or other forms of expression to be powerful ways to process grief and loss.

Facing too many losses at once or losing someone when you are experiencing other stresses or hardships needs even more attention. If you had a difficult relationship with the person you lost, you may be working through a bigger mix of emotions which may take more time.

When supporting another person, you can accompany them as they go through pain, but your job is not to take away the pain or tell them when it will go away. Accept their feelings and their timeline. You can be a comforting presence; listen if they want that, and find out if there are tasks or responsibilities you can take off their plate.

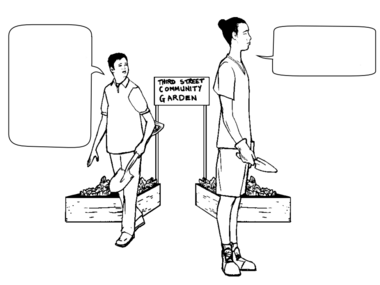

Hey, you came early today! Oh—are you all right?

Yeah, well,

not really… | |

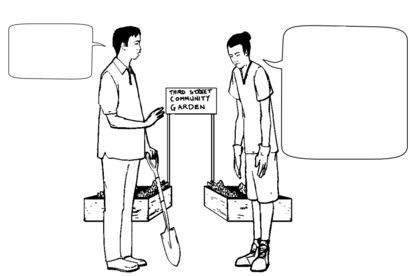

Is it OK to ask?

Remember I told you my grandma was sick, the one who taught me to garden? She passed 3 days ago. | |

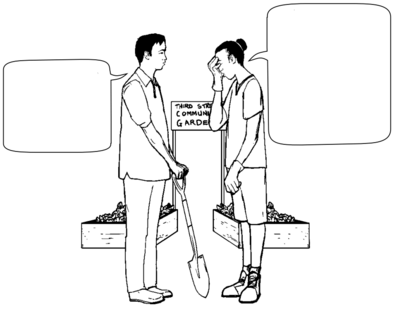

I am so sorry. Do you want to sit? Take your time…

I thought being in the garden would help, but… it’s so hard. She really is the person who raised me. | |

| Showing kindness or taking a moment to be with someone in grief or after a loss, even if you don’t know them, can make a difference. Just being present with someone and listening, if they feel like speaking, is a good way to provide support. |  It feels like honoring her to be here. I feel her with me.

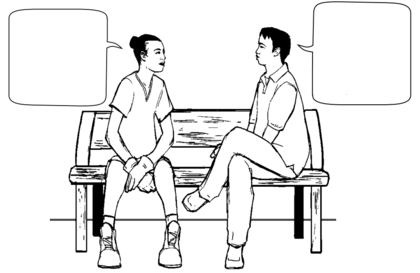

That makes sense. If you want, tell me a little about her… |

When loss can lead to mental health problems

A blocked grieving process can lead to mental health challenges, especially depression. Emotional difficulties can be created or made worse by ideas about when and how much grief is OK to feel.

Mismatched timeline. People often say or act like you should be “over it” or should “move on” when that does not match where you are. Though calming for some, routine caretaking or meeting other family expectations and household tasks can feel overwhelming when trying to grieve. Society, the workplace, or religious rituals may expect you to grieve at a different pace than your feelings are developing. You may have no or too little time off before you are expected to return to work, or be expected to participate in observances that schedule certain feelings to specific time periods.

Conflicted feelings. Having difficult or mixed feelings about the person before they died, such as being angry at them or feeling guilty you didn’t do more for them, can make it harder to feel settled about their death.

Hiding grief. Stigma and shame can block the grieving process. For example, if you lose a loved one to a drug overdose, you may feel shame or anger about their substance use, and this can block your grief.

Avoiding grief. Using alcohol or other substances to manage emotional pain, working too many hours, or relying on television, video games, or online scrolling to avoid thinking about the loss can displace the grieving process. While distraction from grief may be helpful at times, it can also prevent the release that you will feel by going through necessary grieving.

Needing more help. Sometimes, the hard feelings of loss don’t get better even after time passes. Painful emotions remain severe and interfere too much with life. If signs of depression make you think someone is not recovering from loss or is not able to move through a grieving process even with the help of their friends and family, try to connect them with mental health support. Some common experiences with grief—for example, not sleeping or eating well, losing interest in regular activities—do not always mean a person has depression, however, even though the signs may look the same.

Helping children with loss

Children grieve differently than adults, in ways related to their age. Young children can know when they or someone else in their household is very ill, or when someone has died. They may not understand all the actions and feelings of people around them, but they know when something is wrong.

When someone is very ill or, following an accident or after someone has died, everyone in the family feels distress, including the children. A child may respond by misbehaving, wetting the bed, not eating, not speaking, or acting younger than their age. Children do not decide to do these things; they just have no other ways to show their distress. Helping them learn how to process their feelings will help them throughout their entire life.

Ways to prepare a child for loss

Many families avoid talking with children about serious illness, death, divorce, and other serious situations because they think that not hearing about such problems protects them. But not talking with children may leave them afraid of what is happening, alone with their fears, and shocked later if there is a death or someone close to them is no longer there.

Talking with a child about these topics can be difficult, but helping children prepare to face a difficult situation or death in the family, and then talking with them about it afterwards, is very important. How a child reacts to upsetting news often depends on how the adults are handling it. When adults appear strong and calm, children often respond that way too.

Allow children to ask questions. Answer their questions honestly, giving them truthful information they can understand based on their age and ability to understand. Share small amounts of information over time as the child adjusts to what they see happening. Let them know any feeling they have is OK to have and OK to tell you about. For example, a child might reveal their worry that it was their behavior that caused a person’s illness or accident, and they need to be reassured that is not true. Show them understanding and affection, praise them when they do something well, spend time with them, and give them the attention all children need.

Community support for grieving

Helpful traditions. Ask about and offer ways to connect people to others who share their traditions about death and grief. Especially when someone has moved recently, or is from another country, they may want to reconnect with cultural traditions but do not know where to find others who share them.

Create meaning. Many people find comfort in organizing to prevent others from going through what they did. People may share powerful testimonies, work to change policies, or raise money for a larger cause when their loss is related to a specific illness, type of violence, or accident. Joining with others in common cause creates bonds and emotional support. Creating resources and support networks can bring comfort in knowing that the next person needing the same information will benefit from your experience.

Commemoration and memory. Religious and spiritual practices help many people find comfort or meaning after a loss. People can also create their own spaces or moments in which to remember and honor loved ones. This can be as simple as lighting a candle or finding a beautiful spot for quiet reflection. These occasions can be very personal, shared only by family, or more public. The Mexican and Central American tradition of creating altars to express both celebration and sadness on the yearly Day of the Dead has inspired many beautiful and meaningful altars to individuals and groups, for example, people who were victims of gun violence or partner violence or died crossing the southern US border.

Permanent community-designed monuments, plaques, parks, and gardens mark important sites and keep the memory of people or group histories alive as well as creating places to gather. Monuments can be mobile too. The AIDS Memorial Quilt is made of thousands of quilt sections sewn by families and loved ones of people who died from AIDS. As the AIDS Quilt travels, it brings people together to remember loved ones and celebrate life.