Hesperian Health Guides

Gender-based violence

HealthWiki > Promoting Community Mental Health > Chapter 5: Violence and anger > Gender-based violence

Being aware of this reality and the different forms it takes is part of being prepared to deal with it. For example, a person being hurt by a partner might tell you directly or you might actually see physical marks. Or you might notice signs of fear or that something seems wrong. When a woman says she can’t attend evening meetings, is it because her partner controls what she does? Or maybe it is unsafe for her to walk at night? Talking with her may reveal what is going on and what might be done about it: have another group member accompany her to and from meetings; connect her to domestic violence services and a place where she will be safe (both she and her partner will need help); or plan a neighborhood-based violence intervention such as a Take Back The Night march, where large numbers of people noisily walk the streets together to show how everyone should feel safe.

Contents

Sexual violence

Forced sex or any sex that is not wanted or agreed to is rape. Sexual violence also includes unwanted sexual touching, sexual harassment, and stalking. Sexual violence may come from strangers, but most often it is from someone a person knows: a family member, romantic partner, date, classmate, neighbor, or friend. Knowing and having trusted the person who assaulted you can make sexual violence even more difficult to talk about and recover from.

Many college students have never discussed sexual violence or do not know what to do if they witness or experience it. Non-profit It’s On Us is building a student-led movement against sexual assault through chapters that carry out awareness and prevention trainings for peer-education. They provide students, especially young men, with tools to address the cultural norms at the root of sexual harm and instead foster a culture of violence prevention.

Support for sexual violence survivors

A person who has been raped or sexually assaulted needs first aid for any physical injuries. They may need medicine to prevent pregnancy or sexually transmitted infections. Most hospital emergency rooms have staff trained to support sexual violence victims and can document the injuries. This record will be necessary if the case is reported to the police, even if that decision is not made until much later.

The person needs emotional first aid at the same time. You can help them connect with organizations that provide counseling, find other survivors to talk with, and anything else they need.

Supporting survivors’ healing process

The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) is the nation’s largest anti-sexual-violence organization. RAINN created the National Sexual Assault Hotline (1-800-656-HOPE) in partnership with more than 1,000 local sexual assault service providers across the US and runs programs to prevent sexual violence, help survivors, and ensure that perpetrators are brought to justice. Hotline staff recommend using specific phrases when talking to survivors.

“I believe you. It took a lot of courage to tell me about this.” It can be very difficult for survivors to share their story. They may feel ashamed or worry they won’t be believed. Leave “why” questions for later—your priority is to offer support. Do not assume that calmness means the event did not occur or harm them—everyone responds to trauma differently.

“It’s not your fault. You didn’t do anything to deserve this.” Survivors may blame themselves, especially if they know the perpetrator. Remind them, more than once, that they are not to blame.

“You are not alone. I care about you and am here to help.” Let the survivor know you are there for them and willing to listen. Make sure they know there are other survivors and counselors who can help them heal.

“I’m sorry this happened, it should not have happened to you.” Acknowledge the experience has affected their life and the healing process will take time.

Intimate partner violence

The domestic violence prevention movement has raised awareness that violence takes many forms. In addition to hitting and other physical violence, advocates and activists also focus attention on harms from actions taken to intimidate and control others. Also, while most intimate partner violence is carried out by men harming women, abusive behavior can come from and be directed toward persons of any gender and sexuality, and happen in gay, straight, or other kinds of relationships.

Warning signs: Abusive behaviors are violence. Control over another person can take many forms. Pay attention to signs of physical as well as emotional violence. You might notice someone mentions that their spouse doesn’t like them to go out, or they worry about how their ex-partner treats their children. Other warning signs include a partner who is jealous, controls access to money and resources (like a car), pressures for sex or drug use, or threatens with words, actions, or both.

Understanding power and control

Activity

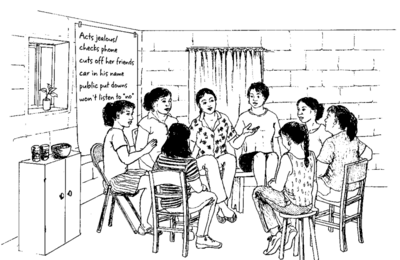

Look at power and control in relationships

- At the top of a large sheet of paper or whiteboard, write: “Signs of control and abuse.”

- Ask the group to list examples of how one person can abuse or control the other person in a relationship. These could be examples that are commonly understood to be abuse, such as hitting or always yelling at them. Add other ways a person is limited by a partner such as: controlling access to money, stopping someone from getting a job, not allowing visits with family or friends, constant insults, telling the person she imagines things, or limiting access to children. You could also group examples under categories like: economic, intimidation, isolation, technology, using the children, or others.

- Talk about how warning signs often occur before there is physical violence and that some may be daily events. Discuss how it may be harder for someone to recognize these signs compared to signs of abuse that are more commonly thought of as violence. You may also want to discuss examples that reflect how family histories or cultural traditions consider or ignore abuse in how men treat women or how parents treat children.

Support for someone experiencing intimate partner violence

Be prepared to lend support by keeping a list of local hotlines, counseling programs, or shelters as well as state or national resources (like the National Domestic Violence hotline: 1-800-799-7233). People who are experiencing or have experienced intimate partner violence need emotional and practical support.

Emotional support, as they process complex feelings and decide next steps, can include:

- acknowledging their situation is difficult and they are brave to take control of it.

- not judging their decisions, including if they leave and then return to an abusive partner.

- helping them create a safety plan.

- offering to go with them for moral support when they visit a service provider or legal setting.

Practical support, especially if the person depends financially on an abusive partner or otherwise lacks resources, can include:

- suggesting where they can get help with housing, food, health care, and other needs.

- advising where they can learn about their legal rights and get legal aid.

- storing copies of their important documents or a backpack with items they’ll need in case of an emergency.

- encouraging them to talk to hotlines, people, or programs that can provide guidance.

- helping them document specific instances of violence, threats, or harassment by writing down what happened and when. Also help them take pictures of injuries and screenshot text messages.

- not posting information on social media that could be used to identify them or where they spend time.

- notifying (with their permission) specific neighbors or co-workers about the situation and what to do (and what not to do) if the abuser appears at their home or work.

Help for the person causing abuse

In some cases, abusers may not appear to others as a threat, especially if they seem likeable or calm. The abuser may be good at presenting their violence as justified (“I was provoked”) or apologizing and promising it won’t happen again. People who abuse their partners usually need help to stop. Become familiar with local resources that help abusers to change. If it is safe, you can express concern and point out the harmful consequences of their abuse. Point out what is at stake based on what is important to them: they could be arrested, destroy their relationship, harm their children who witness violence, lose access to their children, incur legal or other expenses, or ruin their reputation. Assure them that with the right help and longterm support, a person who abuses can change.

Create accountability for those who hurt others. Emerge Counseling and Education to Stop Domestic Violence in Massachusetts has been working with perpetrators of violence for years. Their long-term, profound approach goes beyond anger management to help perpetrators address the root causes of abuse. Their Intimate Partner Abuse Education Programs center on how the person who commits abuse is entirely responsible for their abusive behavior and ways they can become accountable for their actions. They work directly with victim advocacy programs.

Healthy relationships help prevent violence

Most young people learn about sex and relationships from a mix of family and friends, school, music and movies, pornography, and social media. Modeling healthy relationships and opening discussions about communication in relationships, consent around sexual activity, and handling feelings are important ways to prevent sexual and intimate partner violence.

Healthy relationships and becoming an adult.

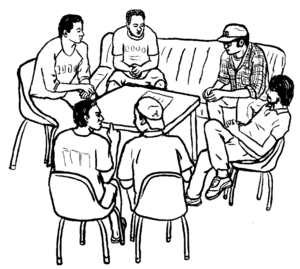

Coaching Boys Into Men (CBIM) is a violence prevention program that uses the attraction of sports and the relationships between coaches and young male athletes to teach healthy relationship skills, especially that violence is not the same as strength. The program offers a set of activities built around brief weekly team discussions led by the coach. A single coach can do the program with a single sports team, or entire schools or school districts can get involved in promoting the development of a common language and understanding among young people. Discussion topics include identifying insulting language, disrespectful behavior (in person and online), consent with romantic partners, and talking through how the aggression promoted in sports should not carry over into relationships. In 2022, the program broadened its focus on young people’s mental health needs.

The CBIM program has changed group culture to where young men now call out the offensive behavior of others, even when adults are not present. The CBIM curriculum is free online and is used across the US and, increasingly, in other countries.