Hesperian Health Guides

Testing Range of Motion of Joints and Strength of Muscles

HealthWiki > Disabled Village Children > Chapter 4: Examining and Evaluating Children with Disabilities > Testing Range of Motion of Joints and Strength of Muscles

Loss of strength and active movement may in time lead to a stiffening of joints or shortening of muscles (contractures). As a result, the affected part can no longer be moved through its complete range of motion.

Contents

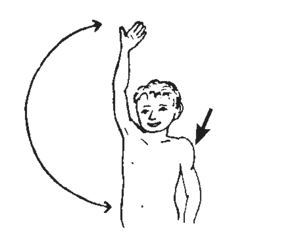

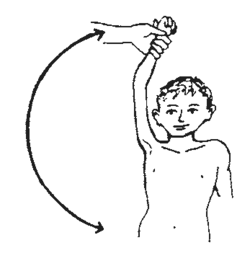

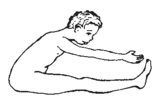

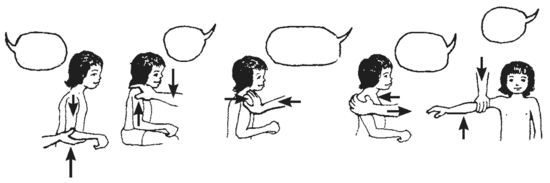

Active movement

| The shoulder muscles can usually raise the arm until it is straight up. | When the shoulder muscles are paralyzed, the child can no longer actively lift his arm. |

Range of active motion

shoulder muscles used to raise arm |

shoulder muscles small and weak

Reduced range of active motion |

| Lifting the arm like this with the arm’s own muscles is called ACTIVE MOTION. | |

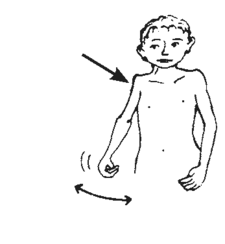

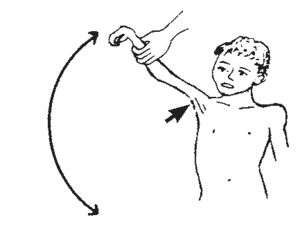

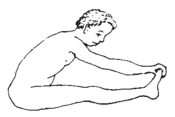

Passive movement

| At first the paralyzed arm can be lifted straight up with help. This is called PASSIVE MOTION. | Unless the full range of motion is kept through daily exercises, the passive range of motion will steadily become less and less. |

Range of passive motion

|

tight cords and skin

Reduced range of passive motion |

| Now the arm cannot be raised straight up, even with help. | |

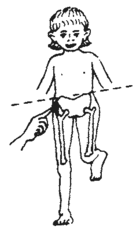

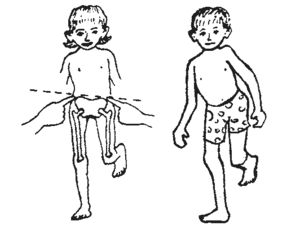

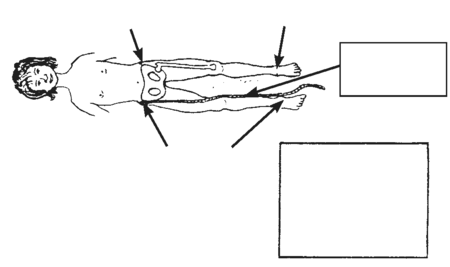

In the physical examination of a child with any weakness or paralysis of muscles, or joint pain, or scarring from injuries or burns, it is a good idea to test and record both range of motion and muscle strength of all parts of the body that might have contractures or be affected. There are 2 reasons for this:

- Knowing which parts of the body have contractures or are weak, and how much, can help us to understand why a child moves or limps as she does. This helps us to decide what activities, exercises, braces, or other measures may be useful.

- Keeping accurate records of changes in muscle strength and range of motion can help tell us if certain problems are getting better or worse. Regular testing therefore helps us evaluate how well exercises, braces, casts, or other measures are working, and whether the child’s condition is improving, and how quickly.

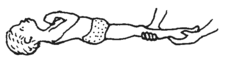

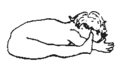

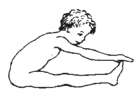

Before testing range of motion and muscle strength in children with disabilities, it helps to first test children without disabilities of similar ages, to know what their usual ranges of motion and muscle strengths are. Age matters because babies are usually weaker and have much more flexible joints than older children. For example:

|

|

|

|

| A baby’s back and hips bend so much he can lie across his straight legs. | A young child bends less but can usually touch his toes with his legs straight. | Around 11 to 14 it is harder to touch toes. His legs grow faster and become longer than his upper body. | Later, upper body growth catches up with legs. He can again touch toes more easily. |

In different children (and sometimes in the same child) you may need to check range of motion and strength in the hips, knees, ankles, feet, toes, shoulders, elbows, wrists, hands, fingers, back, shoulder blades, neck, and jaw. Some joints have 6 or more movements to test: bending, straightening, opening, closing, twisting in, and twisting out. See, for example, the different hip movements (range-of-motion exercises) in Chapter 42.

To test both range of motion and strength, first check range of motion. Then you will know that when a child cannot straighten a joint, it is not just because of weakness.

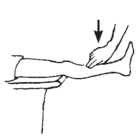

Range-of-motion testing:

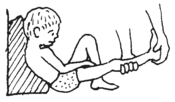

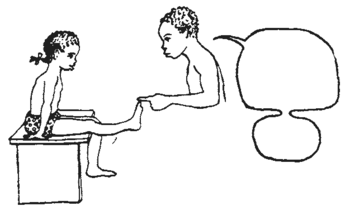

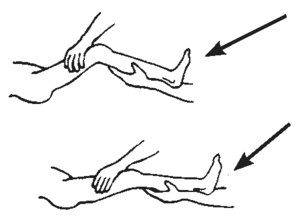

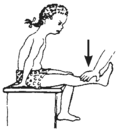

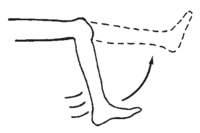

Knee

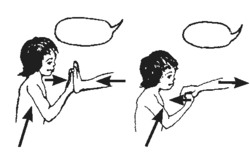

| 1. Ask the child to straighten it as much as she can. |

Raise your foot and touch my finger.

Good girl!

|

2. If she cannot straighten it all the way, gently see how far you can straighten it without forcing.

3. If at first the joint will not straighten, keep trying with gentle continuous pressure for 2 or 3 minutes.

4. If a joint will not straighten completely, try with the child in different positions.

|

For example, a knee often does not straighten as much with the hips bent as with the hips straight. |  Now it straightens more. |

For this reason, each time you test range of motion to measure changes, be sure the child is in the same position. |

Position affects how much certain joints straighten or bend. This is true in any child, but especially in a child with spasticity.

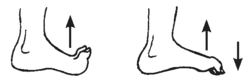

5. In addition to checking how much a joint straightens, check how much it bends.

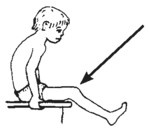

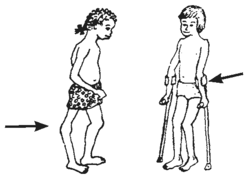

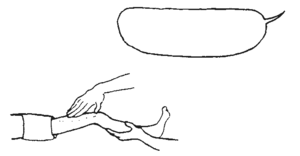

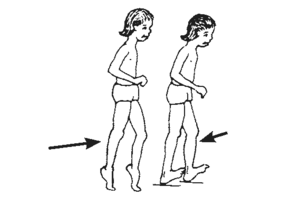

| 6. Also check for too much range of motion. |

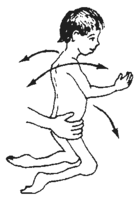

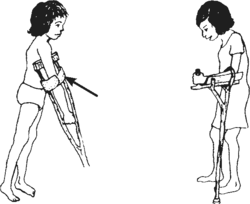

A child who walks on a weak leg often ‘locks’ her knee backward to keep from falling. In time, the knee stretches back more and more, like this.

The same thing can happen to the child with weak arms who uses crutches (or crawls).

|

Usually the best positions for checking range of motion are the same as those for doing range-of-motion and stretching exercises. These are shown in Chapter 42.

For methods of measuring and recording range of motion, see Chapter 5.

Precautions when testing for contractures

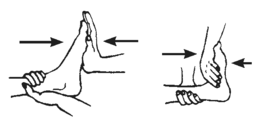

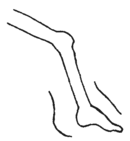

Testing range of motion of the ankles, knees, and hips is important for evaluating many children with disabilities. We have already discussed knees. Here are a few precautions when testing for contractures of ankles and hips

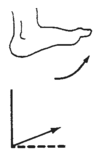

Ankle

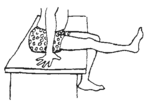

Hip

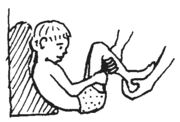

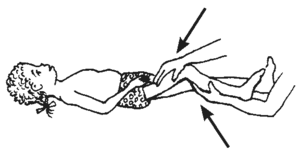

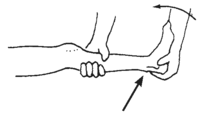

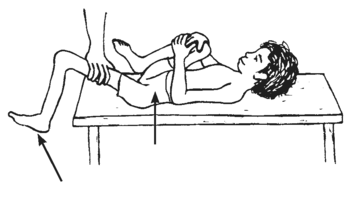

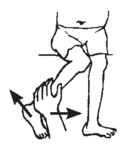

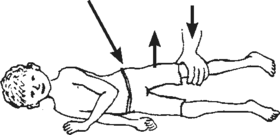

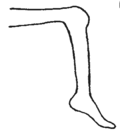

To check how far the hip joint straightens, have the child hold his other knee to his chest, like this, so that his lower back is flat against the table. If his thigh will not lower to the table without the back lifting, he has a bent-hip contracture.

|

RIGHT |

|

WRONG |

Muscle testing

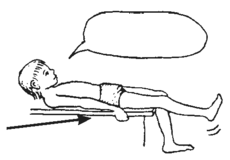

Muscle strength can be anywhere between typical and zero. Test it like this:

| If the child can lift the weight of leg all the way, press down on it, to check if she can hold up as much weight as is typical for a girl her age. If she can, her strength is TYPICAL. |  TYPICAL strength |

| If she can hold some extra weight, but not as much as is typical, she rates GOOD. |

Press down lightly

GOOD strength |

| If she can just hold up the weight of her leg, but no added weight, she rates FAIR. | If she cannot hold up the weight of her leg, have her lie on her side and try to straighten it. If she can, she rates POOR. |

FAIR strength |

POOR strength |

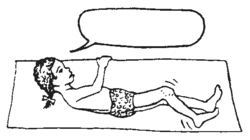

| If she cannot straighten her knee at all, put your hand over the muscles as she tries to straighten it. If you can feel her muscles tighten, rate her TRACE. | |

Muscles move, but not leg:

TRACE strength

No muscle movement:

ZERO strength

Try as hard as you can to straighten your leg. | |

Test the strength of all muscles that might be affected. Here are some of the muscle tests that are most useful for figuring out the difficulties and needs of different children.

Note: These tests are simple and mostly test the strength of groups of muscles. Rehabilitation therapists know ways to test for strength of individual muscles.

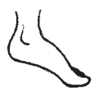

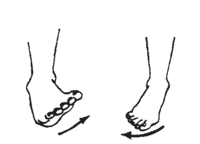

Ankle and Foot

| If the child can walk, see if she can stand and walk on her heels and her toes. |

TYPICAL calf muscle

TYPICAL foot-lift muscle |

Note: Sometimes when the muscles that usually lift the feet are weak, the child uses his toe-lifting muscles to lift his foot. |

| If he lifts his foot with his toes bent up, like this, | see if he can lift it with his toes bent down, like this. |

|

|

Also notice if the foot tips or pulls more to one side. This may show muscle imbalance.

To learn about which muscles move body parts in different ways, as you test muscle strength, feel which muscles and cords tighten.

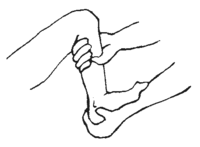

Knee

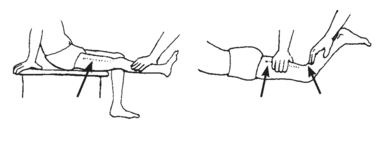

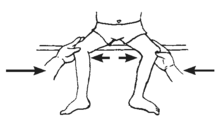

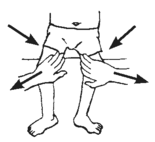

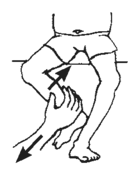

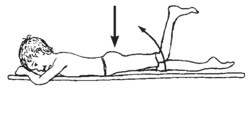

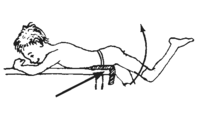

Hips

| OPENING | CLOSING | ROTATING HIP OUT (and leg in) | ROTATING HIP IN (and leg out) |

|

|

|

|

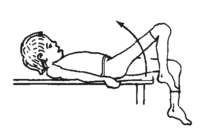

| STRAIGHTENING | |||

| BENDING | Feel the butt muscles tighten. | If the hip has contractures, test with legs off end of table. | |

|

|

padding | |

| SIDEWAYS LEFT Feel the side-of-hip muscles tighten here. |

|

Note: Weak hip muscles sometimes lead to dislocation of the hip. Be sure to check for this, too.

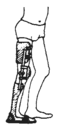

Testing side-of-hip muscles is important for evaluating why a child limps or whether a hip-band may be needed on a long-leg brace.

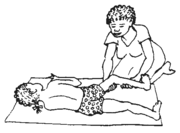

Stomach and Back

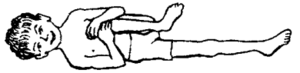

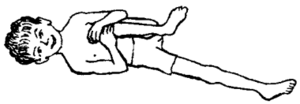

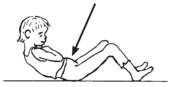

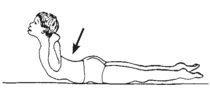

| To find out how strong the stomach muscles are, see if the child can do ‘sit ups’ (or at least raise his head and chest). | To test the back muscles, see if he can bend backward like this. |

|

| Sitting up with knees bent uses (and tests) mainly the stomach muscles. Feel stomach muscles tighten. | Sitting up with knees straight uses the hip-bending muscles and stomach muscles. | Feel the muscles tighten on either side of the backbone. Notice if they look and feel the same or if one side seems stronger. |

|

|

|

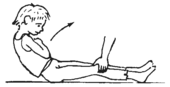

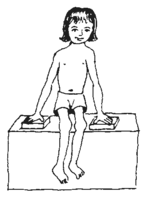

You can check a child’s trunk control and strength of stomach, back, and side muscles like this. Have him hold his body upright over his hips, then lean forward and back, and side to side, and twist his body.

If a child’s stomach and back muscles are weak, he may need braces with a body support—or a wheelchair.

Shoulders, Arms, and Hands

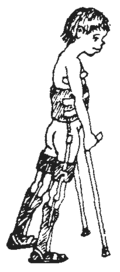

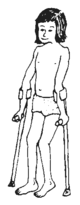

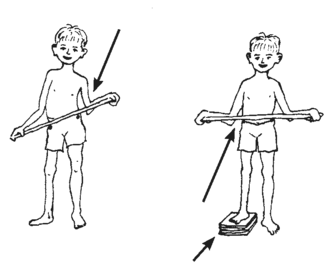

When a child’s legs are severely paralyzed but she has FAIR or better trunk strength, she may be able to walk with crutches if her shoulders, arms, and hands are strong enough.

| Therefore, an important test is this: |  |

| Can she lift her butt off the seat like this? | |

| If she can, she has a good chance for walking with crutches. |

If she cannot lift herself, check the strength in her shoulders and arms:

ARMS

SHOULDERS

If the shoulder pushes down strongly but her elbow-straightening muscles are weak, she may be able to use a crutch with an elbow support.

Or, if her elbows have full range of motion, she may learn to “lock” her elbow back like this. However, this can lead to elbow problems.

You may want to make a chart something like this and hang it in your examining area, as a reminder.

Evaluating Strength or Weakness of Muscles | |||

|

CAUTION! To avoid misleading results, check range of motion BEFORE testing muscle strength. | |||

| Strength rating | Test with the child positioned so that he lifts the weight of the limb. | ||

|

TYPICAL (5) |

lifts and holds against strong resistance |  |

| GOOD (4) |

lifts and holds against some resistance |  | |

| FAIR (3) |

lifts own weight but no more |  | |

| Test with the child positioned so that he can move the limb without lifting its weight (by lying on his side). | |||

|

POOR (2) |

cannot lift own weight but moves well without any weight. |  |

| TRACE (1) |

barely moves |  | |

| ZERO (3) |

no sign of movement |  |

|

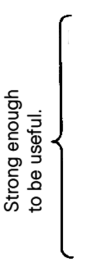

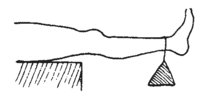

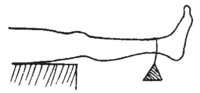

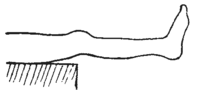

In muscle testing, it is especially important to note the difference between FAIR and POOR.

This is because FAIR is often strong enough to be fairly useful (for standing, walking, or lifting arm to eat). POOR is usually too weak to be of much use.

Sometimes with exercise POOR muscles can be strengthened to FAIR; this can greatly increase their usefulness. It is much less common for a TRACE muscle to increase to a useful strength (FAIR), no matter how much it is exercised. (However, if muscle weakness is due to lack of use, as in severe arthritis, rather than to paralysis, a POOR muscle can sometimes be strengthened with exercise to GOOD or even TYPICAL. Also, in very early stages of recovery from polio or other causes of weakness, POOR or TRACE strength sometimes returns to FAIR or better.)

Other things to check in a physical examination

then raise the foot of the short leg until the hips are level

have her lie as straight as she can. Feel and then mark, on both sides of her body, the bony lumps

June 3, 1986 |---|

Sept. 10, 1986 |-----|

Dec. 2, 1986 |-------|

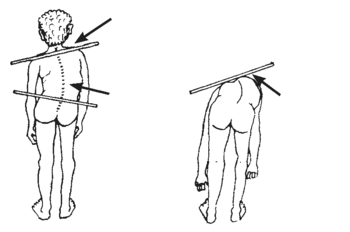

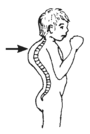

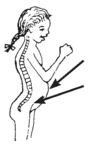

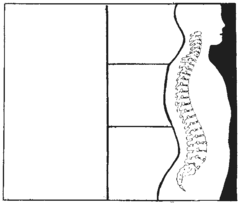

Curve of the spine Especially when one leg is shorter or there are signs of muscle imbalance in the stomach or back, be sure to check for one of the following main types of spinal curve (which may occur separately or in combination):

| Sideways curve (scoliosis) | |

shoulder higher on side of short leg

Check for weaker muscles on this side of spine.

Have the child bend over. Check for a rib hump on outer side of curve. |

| Hunch back, rounded back (kyphosis) | Swayback (lordosis) | ||

| May result from weak back muscles, or poor posture. |  |

|

May result from weak stomach muscles or bent-hip contractures. (Be sure to check for these.) |

Some spinal curves will straighten when a child changes her position, lies down, or bends over. Other spinal curves will not straighten, and these are usually more serious. For more information about examining spinal curve and deformities of the back, see Chapter 20.