Hesperian Health Guides

Chapter 31: Hearing Loss and Communication

More often, children have partial hearing loss. A child may show surprise or turn her head to a loud noise, but not to softer noises. She may respond to a low-pitched sound like thunder, a drum, or a cow’s “moo,” but not to high-pitched sounds like a whistle or a rooster crowing. Or (less commonly) a child may respond to high-pitched sounds but not low ones.

|

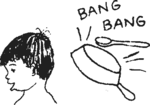

A child with complete hearing loss does not respond even to very loud noises. (But he may notice movements or vibrations caused by sudden loud noises. For example, clapping behind the child’s head may move the air at his neck and cause the child to turn.) |

|

A child with partial hearing loss hears some sounds, but may not hear clearly enough to tell the difference between certain sounds or words. Families may take a long time to recognize that these children have difficulty hearing. |

Some children with partial hearing loss hear a little when people speak to them. They take longer to recognize and respond to some words. But many words they do not hear clearly enough to understand. They are slow to begin to speak. Often they do not speak clearly, mix up certain sounds, or seem to “talk through their nose.” Unfortunately, sometimes parents, other children, and teachers do not realize that the child has difficulty hearing. They may treat her as if she has cognitive delay or low intelligence. This only increases the child’s problems.

For growing children, hearing and language are very important for getting to know, understand, and relate to the people and things around them. The exchange of ideas and information through some form of communication is important for the brain development of all children. And for their mental ability to develop fully, they need to learn to communicate well from an early age.

For a child with a hearing loss, who cannot hear words clearly, it is much more difficult for her to understand what is going on around her and to learn to speak. So she has trouble both understanding what people want, and telling them what she wants. This can lead to frequent disappointments and misunderstandings, both for the child and others. As a result, children with hearing loss may take longer to learn to relate to other people, feel lonely or forgotten, or develop behavior problems.

Because they have difficulty communicating, children with hearing loss are also more likely to suffer sexual abuse (see Helping Children Who Are Deaf).

How hearing loss affects a child depends on:

- When the hearing loss began. For a child who has severe hearing loss before he begins to speak, learning to speak or “read lips” will be far more difficult than for a child who loses his hearing after he has begun to speak.

- How much the child still hears.A child with less severe hearing loss may have less difficulty learning to speak, understand speech, and “read lips.”

- Other disabilities. A child with hearing loss who is also visually impaired, has cognitive delay, or has multiple disabilities will have a harder time learning to communicate than a child with hearing loss only (see “Causes of Hearing Loss,” below).

- How soon hearing loss is recognized.

- How well the child is accepted, and how early he is helped to learn other ways to communicate.

- The system of communication that is taught to the child (“Oral” or “Total,” see "Different Ways to Help a Child Communicate").

Importance of early recognition of hearing loss

During the first years of life, a child’s mind is like a sponge – it learns language very quickly. If a child’s hearing loss is not recognized early and effective help is not provided, the best years for learning communication skills may be lost (age 0 to 7). The earlier language training begins, the more a child can learn to communicate.

Parents should watch carefully for signs that show if a baby hears or not. Does the baby show surprise or blink when you make a sudden loud noise? As the baby grows, does he turn his head or smile when he hears familiar voices? Has he begun to say a few words by 18 months of age? Does he say a lot of words fairly clearly by age 3 or 4? If not, he may have hearing loss. As soon as you suspect a problem, test the child’s hearing.

Do simple tests for hearing. If it seems the child has hearing loss, when possible, take him to a specialist for testing.

The following 2 stories will help show the difference that it can make to recognize hearing loss early and provide the extra help that the child needs.

TONIO

Although Tonio was born with a severe hearing loss, his parents did not realize this until he was 4 years old. For a long time, they thought he was just slow. Or stubborn.

Until he was one year old, Tonio seemed to be doing fairly well. He began to walk and play with things. Then his sister, Lota, was born. Lota smiled and laughed more than Tonio when their mother talked or sang to her. So their mother talked and sang to Lota more.

By the time Lota was 1, she was already beginning to say a few words. Tonio had not yet begun to speak. “Are you sure he can hear?” a neighbor asked one day. “Oh yes,” said his mother. She called his name loudly, and Tonio turned his head.

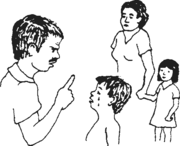

When he was 3, Tonio could only say 2 or 3 words. Lota, at age 2, now spoke more than 200 words. She asked for things, sang simple songs, and played happily with other children. Tonio was more moody. Mostly he played by himself. When he played with other children it often ended in fighting—or crying.

Lota behaved better than Tonio. Usually, when her mother told her not to do something and why, she understood and obeyed. Often, to make Tonio obey, his mother would slap him.

One time in the village market Lota asked for a banana and her mother bought her one. A moment later, Tonio quietly picked up a mango and began to eat it. His mother slapped him. Tonio threw himself on the ground and began to kick and scream.

When Tonio’s father heard what had happened in the market, he looked angrily at Tonio and said, “When will you learn to ask for things? You’re 4 years old and still don’t even try to talk. Are you stupid, or just lazy?”

Tonio just looked at his father. Tears rolled down his cheeks. He could not understand what his father said. But he understood the angry look. His father softened and took him in his arms.

Tonio’s behavior got worse and worse. At age 4 his mother took him to a health worker, who tested Tonio and found that he had complete hearing loss.

Now Tonio’s parents are trying to make up for lost time. They try to speak to him clearly and slowly, in good light, and to use some signs and gestures with their hands to help him understand. Tonio seems a little happier and speaks a few more words. But he still has a lot of trouble saying what he wants.

SANDRA

When Sandra was 10 months old, her 7-year-old brother, Lino, learned about testing for hearing loss as part of the CHILD-to-child program at school. So he tested his baby sister. When he stood behind her and called her name or rang a bell, she did not turn or even blink. Only when he hit a pan hard did she show surprise. He told his parents he thought Sandra did not hear well. They took Sandra to a small rehabilitation center. A worker there tested Sandra and agreed she had a severe hearing loss.

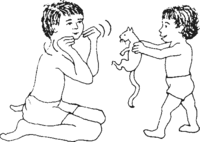

The village worker explained what the family could do to help Sandra develop and learn to communicate. He gave them many drawings of hands held to make ‘signs’ for common words.

“Every time you speak, make ‘signs’ with your hands to show what you mean. Include all the signs and gestures that people already use in your village. Teach all the children to use them too. Make a game out of it. At first Sandra won’t understand. But she’ll watch and learn. In time she’ll begin to use signs herself.”

“If she gets used to signs, won’t that keep her from learning to speak?” asked her father.

“No,” said the worker. “Not if you always speak the words at the same time. The signs will help her understand the words, and she may even learn to speak earlier. But it takes years to learn to speak with ‘lip reading’. First, she needs to learn to use signs to say what she wants and to develop her mind.”

Sandra’s family began using signs as they spoke to each other. Months passed, and still Sandra did not begin to speak or to make signs. But now she was watching more closely.

By age 3, Sandra began to make signs. By age 4 she could say and understand many things with signs—even lip read a few words, like “Yes,” “No,” and “Lino.” By age 5 she had only learned to lip read a few words. But with signs she could say over 1000 words and many simple sentences.

Sandra was happy and active. She liked to color pictures and play guessing games. Lino began to teach her how to draw letters. One day she asked Lino when she could go to school.