Hesperian Health Guides

Questions About Cerebral Palsy

Contents

1. What causes it?

Cerebral palsy affects different parts of the brain in every child with this disability. The causes are often difficult to find.

Causes before birth:

- Infections of the mother while she is pregnant. These include German measles (rubella), chicken pox, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and some bacterial infections.

- Differences between the blood of mother and child (Rh incompatibility).

- Conditions in the mother, such as gestational diabetes or toxemia of pregnancy.

- Inherited. This is rare, but there is familial spastic paraplegia.

- No cause can be found in about 30% of the children.

Causes around the time of birth:

- Prematurity. Babies born before 32 to 37 weeks and who weigh under 2.5 kilos (5.5 pounds) are more likely to have cerebral palsy. In rich countries, over half the cases of cerebral palsy happen in babies that are born early.

- Birth injuries from difficult births. These are mostly large babies of mothers who are small or very young. The baby’s head may be pushed out of shape, blood vessels torn, and the brain injured.

- Lack of oxygen (air) at birth, although this does not often cause CP. The baby does not breathe soon enough and becomes blue and limp. In some areas, misuse of medicines (oxytocics) to speed up birth harms the flow of blood to the baby in the womb so she does not get enough oxygen. In other cases, the baby may have the cord wrapped around her neck. The baby is born blue and limp, with brain injury.

Causes after birth:

- Very high fever due to infection or dehydration (water loss from diarrhea). It is more common in bottle-fed babies.

- Brain infections (meningitis, encephalitis). There are many causes, including cerebral malaria and tuberculosis.

- Head injuries.

- Lack of oxygen from drowning, gas poisoning, or other causes.

- Poisoning from lead glazes on pottery, pesticides sprayed on crops, and other poisons.

- Bleeding or blood clots in the brain, often from unknown cause.

- Brain tumors. These cause progressive brain injury in which the signs are similar to cerebral palsy but steadily get worse.

The injured parts of the brain cannot be repaired, but often the child can learn to use the uninjured parts to do what she wants to do. It is important for parents to know more or less what to expect:

Families can do a lot to help these children learn to function better. Most children will learn to adapt successfully to their condition. When they become frustrated or discouraged, families can find new and interesting ways to keep them progressing. Even children with severe cognitive delay can often learn important basic skills. Only when injury is so great that the child does not respond at all to people and things is there little hope for much progress. However, before judging the child who does not respond, be sure to check for loss of hearing or eyesight.

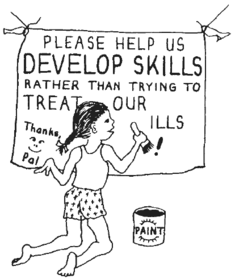

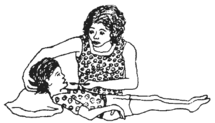

Family members can learn to play and do daily activities with the child in ways that help her both to function better and to prevent secondary disabilities such as contractures.

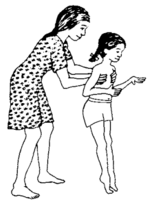

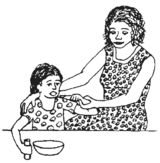

Most important is that the family learn not to do everything for the child. Help her just enough that she can learn to do more for herself.

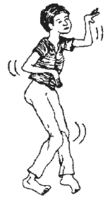

For example, if your child is beginning to hold up her head, and to take things to her mouth,

|

|

| instead of always feeding her yourself | look for ways to help her begin to feed herself. |

6. Will my child ever be able to walk?

- Having confidence in yourself and liking yourself

- Communication and relationship with others

- Self-care activities such as eating, dressing, toileting

- Getting from place to place

- (And if possible) walking

We all need to realize that walking is not the most important skill a child needs,and it is certainly not the first. Before a child can walk he needs reasonable head control, needs to be able to sit without help, and to be able to keep his balance while standing.

Most children with cerebral palsy do learn to walk, although often much later than is typical. In general, the less severely affected the child is and the earlier she is able to sit without help, the more likely she is to walk. If she can sit without assistance by age 2, her chances for walking may be good—although many other factors are involved. Some children begin to walk at age 7, 10, or even older.

Hemiplegic and diplegic children usually do learn to walk, although some may need crutches, braces, or other aids.

Many severely affected children may never walk. We need to accept this, and aim for other important goals. Whether or not the child may someday walk, he needs some way to get from place to place. Here is a true situation that helped us to realize that other things are more important than walking.

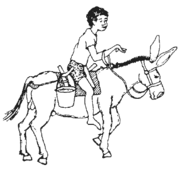

In a Mexican village, we know 2 brothers, both with cerebral palsy.

| Petronio walks but with great difficulty. Walking tires him and makes him feel so awkward that he stays at home and does not play or work. He is unhappy. |  |

| His brother, Luis, cannot walk. But since he was small, he has loved to ride a donkey. He uses a wall to get off and on by himself. He goes long distances and earns money carrying water. He is happy. |  |

(Not only does the donkey take Luis where he wants to go, but by keeping his legs apart, it helps prevent knock-knee contractures. This way ‘therapy’ is built into daily activity.) |