Hesperian Health Guides

Unsafe Disposal of Toxic Waste

HealthWiki > A Community Guide to Environmental Health > Chapter 20: Preventing and Reducing Harm from Toxics > Unsafe Disposal of Toxic Waste

Because toxic wastes can be extremely costly and difficult to dispose of safely, dangerous dumping of wastes is common. And not surprisingly, the dumping usually adds yet another source of illness to the burden of health problems faced by people in poor communities.

More and more businesses are being organized to keep toxic products out of the waste by recycling some or all of their parts. But even environmentally friendly activities such as recycling must be done carefully to prevent toxic materials from harming workers and the environment.

Making sure industries dispose of wastes responsibly is only one part of the solution. To truly end the problem of toxic waste, we must change the way industry works. The only safe way to dispose of toxic waste is to stop creating it in the first place.

Contents

The Africa Stockpiles Programme

Corporations and development agencies have promoted pesticides to farmers for decades as part of a solution to hunger. But many scientists and farmers now recognize that pesticides create more problems than they solve. Who will dispose of these deadly chemicals? How can it be done safely?

In countries across Africa, more than 50,000 tons of unused and unwanted pesticides and other toxic wastes are stored in leaking containers. To clean up these toxics and to prevent the dumping of more poisons, a group of government agencies and international organizations formed the Africa Stockpiles Programme (ASP).

The groups in the ASP have different ideas about how to clean up the waste. Some say the easiest and cheapest way is to burn it. The World Bank and several governments are building incinerators to do this. Other groups in the ASP say burning these wastes would release more poisons into the air and water, and suggest safer disposal methods. As of now, there are no truly safe ways to destroy these chemicals. Developing safer methods will be costlier than burning and will take time.

As the ASP works to solve this problem, toxic wastes blow in the wind and leak into groundwater. These poisons and the sicknesses they cause are part of the deadly legacy of the chemical companies and development agencies that made them and promoted their use.

Battery recycling

Lead acid batteries from cars are commonly recycled for the metals they contain. In most places, this is not an organized industrial process, but is done in homes and backyards. Battery recycling creates serious lead pollution, damaging health and the environment. Short-term exposure to high levels of lead can cause vomiting, diarrhea, convulsions (seizures, “fits”), coma, or even death.

In some places, small household batteries are taken apart and the black powder inside is used to make dyes, inks, and cosmetics. This powder is very poisonous and should never be used for these purposes. It is made of cadmium, lead, zinc, mercury, and other toxic heavy metals. If the powder is used, it should be handled with gloves and face masks, and the waste disposed of safely.

Reducing harm

The best way to reduce exposure to toxins in batteries is for battery producers to collect used batteries and make sure they are recycled under safe conditions. Some countries have laws regulating safe battery recycling.

Electronics recycling

|

| Wearing masks, gloves, and other protective equipment will help protect people who recycle computer parts. |

Producing electronic equipment, such as computers, televisions, cell phones, and radios, requires a large amount of resources. Electronic equipment also contains many toxics such as lead, cadmium, barium, mercury, flame retardants, PCBs, and PVC plastic.

Electronics often end up in landfills where the toxics they contain leach into groundwater. Or they are taken apart and the materials they contain are recycled, often by hand, using dangerous solvents. This causes serious health problems for the people doing the recycling, and moves the toxic materials into other products that will cause more health problems later.

The safest solution is to require companies that produce electronics to take responsibility for safe recycling and to redesign their products to use less harmful materials and to last longer. And the people who buy and use electronic products can reduce harmful waste by having them fixed when they break rather than throwing them out.

Toxic trade

Toxic trade is the export from one country to another of toxic wastes and harmful materials. Because rich countries often try to dump their waste far away, and because governments of poor countries are often powerless to stop them, toxic trade most often means rich countries and rich communities dumping their waste on poorer countries and poorer communities.

Despite international agreements to protect health and the environment, toxic trade is part of global business. Even though they are harmful, products such as tobacco, pesticides, GE foods, asbestos, leaded gas, broken electronics, and others are commonly sent from rich countries to poorer ones.

Some toxic trade is banned by international law. But as many health and human rights activists know, laws only protect people when people organize to enforce them.

Take your toxic waste and go home

The Khian Sea was a ship loaded with 14,000 tons of toxic incinerator ash from the city of Philadelphia in the United States, to be dumped anywhere outside the United States. But wherever it went, people rejected it.

First the ship went to the Bahamas, then the Dominican Republic, but these countries did not accept the waste. It sailed on to Honduras, Bermuda, Guinea-Bissau, and the Netherlands Antilles. But no country wanted the toxic ash.

Desperate to unload, the ship’s crew lied about their cargo. Sometimes they said the ash was construction material or roadfill. But environmental activists kept one step ahead of the ship, letting the countries know what was really in the ash. No one would take it until it got to Haiti. There, the US-backed government allowed the ash, now called “fertilizer,” into the country. 4000 tons of the ash were dumped onto the beach in the town of Gonaives, Haiti.

Before long, public outcry forced Haitian officials to admit they were not getting fertilizer. They ordered the waste returned to the ship. But the Khian Sea had already slipped away in the night.

For 2 years, the Khian Sea went from country to country trying to dispose of the remaining 10,000 tons of ash. The crew was even ordered to paint over the ship’s name. Still, no country was fooled into taking the toxic cargo. A crew member later testified in court that much of the waste was dumped into the Indian Ocean. In the end, 2000 tons of the ash was put in a landfill back in Philadelphia, thanks to years of effort by activists.

Urban construction can unearth toxic waste

Unfortunately, ignoring toxic waste doesn’t make it go away. When new development projects are begun in cities, usually people are excited about the new markets, housing, recreation, and jobs that will be created. But especially when these projects are built where a factory or military base had been, people must be careful to make sure that the very ground itself has not become a toxic waste dump. And if it has, the toxic wastes must be disposed of safely.

A home run for health

When the city of San Diego, USA, began to build a new stadium, fans of the San Diego Padres baseball team were excited. The new stadium would be better for watching games, and building it would bring jobs to the community. But an environmental impact assessment (EIA) showed the project would also have bad affects on the environment and people’s health.

The proposed site was contaminated with toxic chemicals. The plan called for the toxic soil to be dug up and burned right in the middle of the city. Members of a local group, the Environmental Health Coalition (EHC), knew this would cause serious health problems. So they organized the community to demand an alternative.

EHC and community members asked city officials to reject the plan, but the city denied their request. The community then organized more than 100 residents to protest at the building site. When the local media reported it, the San Diego Padres looked like they did not care about their fans. Soon the owners of the team agreed to find another way to get rid of the toxic soil.

The EHC also showed how the new stadium would cause an increase in traffic, air pollution, and asthma among neighborhood children. After many meetings, the Environmental Health Coalition helped develop new, healthier building plans.

Even when public meetings are scheduled and environmental impact assessments are produced, this does not mean that a project will be free from harm. In the case of the San Diego stadium, the developers wanted to go ahead with the project even though they knew about the harm from burning toxic soil and the problems with the stadium plans. It took an organized and dedicated group to study the reports, attend the meetings, and protest in the streets to get the government to reduce harm.

Many people in San Diego pay attention to every game the Padres play. Now they can support their team and know it has not made them sick.

International agreements on toxic waste disposal

For years, rich countries of North America and Europe used Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe as toxic dumping grounds without any legal pressure to stop. Finally, community action in the poorer countries, together with pressure from environmentalists around the world, won international agreements outlawing toxic trade.

The first agreement was the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal (1992). This was won mostly because of the activists who followed the Khian Sea, the ship that traveled around the world trying to dump its cargo of toxic ash. Countries that sign the Basel Convention agree to treat, reuse, and dispose of toxic wastes as close as possible to where they are made, rather than shipping them to other countries.

In 2001, 92 nations signed the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). It bans production and use of the 12 most harmful POPs (called “the Dirty Dozen”) and makes trading them illegal, unless the use of a certain chemical will prevent more harm than it causes (such as targeted use of DDT to control malaria).

A third agreement passed in 2004, the Rotterdam Convention on Prior Informed Consent. This requires a country to notify and get permission from another country when it wants to export harmful chemicals.

When people know about and use these agreements, they can be an important tool to make our world healthier and more just. But there are many ways for countries and corporations to get around the law. For more information on ways to use these and other national and international laws in your struggles for environmental health, see Appendix B.

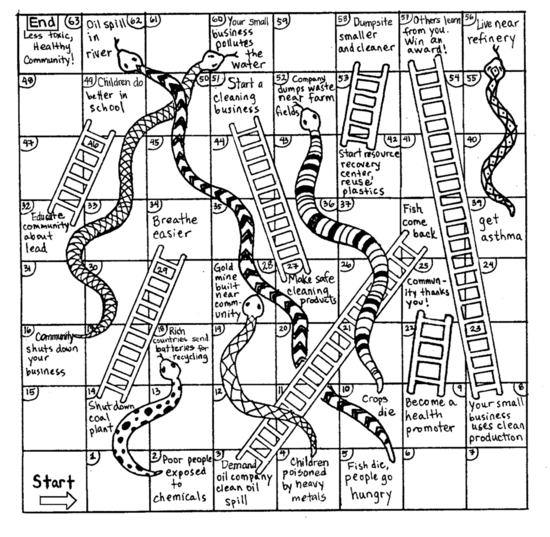

Snakes and ladders game

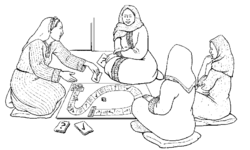

Snakes and ladders is a popular board game used in health education. This version can be played to show the ways that toxics harm us, and how to prevent and reduce harm. You can make your own game board by copying the game board below onto large paper, cardboard, or wood.

Materials: Dice, and seeds, stones, or shells as game markers, and a game board

Rules: This game can be played by 2 to 4 people, or by teams. Each player uses one marker (a seed, stone, or shell) to show what place he or she has on the board.

The first player throws the dice and moves his or her marker according to the number shown, beginning from square 1, marked START.

If a player rolls a 6, the player move 6 spaces and then rolls the dice for a second turn. Otherwise, the dice moves to the next player.

If a marker lands on the head of a snake, the player reads the message on the square out loud, then moves the marker to the snake tail, and reads the message on that square. The player’s next turn starts from there.

If a marker lands at the bottom of a ladder, the player reads the message on the square out loud, then moves the marker to the top of the ladder, and reads the message on that square. The player’s next turn starts from there.

The first player to reach the last square wins. A player must throw the exact number needed to land on the final square.

This game works best when you adapt the messages on the “snake squares” so they refer to health problems and toxics in your community. Also adapt the messages on the “ladders squares” to possible actions to reduce exposure and other solutions relevant to your community.

Encourage the players to discuss the problems (snakes) and solutions (ladders) they land on during the game. When the game is over, ask if there are other problems with toxics that were not mentioned, and what actions people can take to protect their health.

For more information on creating and using board games, see Chapter 11 of Hesperian’s Helping Health Workers Learn.