Hesperian Health Guides

Running support group meetings

HealthWiki > Promoting Community Mental Health > Chapter 8: Support groups > Running support group meetings

Contents

Beginning the meeting

Beginning each meeting in the same way can help people transition from their previous activities to join in common purpose. Try different ways to start the meeting so the group can decide which they like best. Some groups start with each person saying something they are grateful for. Others start by stretching together, saying a prayer, or taking a few quiet moments to write or draw as a way to gather thoughts and “reset,” perhaps in response to the question: “How do you feel right now?” If people check in to say how they are feeling, it may become clear that someone needs special attention that day.

When a group is beginning, it is important to review and remind everyone of the ground rules and see if there are agreements to add or change. When there are new participants, everyone will feel more comfortable when you take time for introductions and give a basic description of how the meeting will proceed.

Encourage participation

Group discussions work best when everyone participates fully and equally, even if this doesn’t come naturally to everyone. Good facilitators draw people out and make everyone feel that their ideas are valuable and worth sharing. This is especially important when people have been made to feel shame about aspects of their educational, cultural, or economic backgrounds.

Here are some strategies to encourage participation:

Pay attention to seating. Arrange people to sit in a circle or some other way where everyone can see each other.

Use a talking stick to take turns. An American Indian tradition is to use an object like a talking stick that is passed among speakers. Everyone listens to and does not interrupt the person holding the stick. If the stick comes to a person who does not want to speak, they pass it to the next person.

Give people a moment to prepare their thoughts. Allow time to think quietly before starting a discussion on a major issue or decision. This helps people prepare and feel more confident to speak.

Be aware of people who are quiet or shy. It can take time for people to feel comfortable sharing, so while you should not pressure or force people to participate, you can make it easier. One way is to ask everyone to write questions or comments anonymously and then read them out loud without saying who wrote what. Also, try going around the room giving everyone a turn to speak. Invite shy people by name to speak if you sense they are ready.

Create small groups. Discuss issues in groups of two or three people, then have them report back to the larger group. People may feel more comfortable speaking with only one other person or reporting on a group opinion rather than stating their own.

Create a story or drawing. Make up a story about a situation similar to those experienced by members of the group. Hearing about the experiences of others can help a person deal with situations they face. The leader can start the story, then ask another member to continue it, and so on until everyone has contributed something and the story is complete. The group can also act out the story as it is told or make a drawing of it. You can ask each person to write or draw in their own notebooks as a way of gathering thoughts or reactions to the collective story.

Use art, theater, movement, and music. Spark people’s creative energy to encourage participation. Drawings, songs, and skits can encourage collaboration among group members and can also be a way for a group to share their ideas with the broader community.

Build capacity and leadership. Allowing people to explore different roles in meetings can help them discover what they are good at. People can take turns leading the group, sending meeting reminders, planning activities, preparing food, or gathering supplies. Sharing different tasks helps people gain experience and encourages involvement from shy people. Draw upon people’s strengths and acknowledge everyone’s hard work along the way, not just the outcome.

Be a good listener and show interest in what people say. It may help both individuals and the group if you briefly echo the main point of what a person said so they know they have been understood. Then invite the next person to speak.

A balance of voices. Using terms like “step up” to encourage people who usually speak less, and “step back” for those who tend to talk more, can help build awareness of participation styles. Find kind and direct ways to ask people to step up and step back such as: “Thanks for adding that. Would someone we haven’t heard from like to go next?” The group can also talk about how people who know they talk a lot can count to 10 before asking to speak, creating some space for shyer people.

Keep the conversation on topic. If someone strays from the topic, first acknowledge their input: “That’s a good point.” Then invite them to relate what they were saying to the topic at hand: “How does does that affect you feeling anxious at work?”

Know yourself. Chapter 9, “Helping ourselves to do this work”, expands more on how group facilitators and others in a helping role can think through everything they bring to their work. For example, when starting a group or running a meeting, it helps to be aware of your own thoughts and feelings about the topic. Ask yourself: “What about this topic makes me uncomfortable or upset? Do my feelings or experiences affect how well I can listen without judging others? How can I make sure I encourage others to think for themselves without imposing my own opinions?” Also, be aware of how others in the group may see you. Perhaps some women will have a hard time trusting men, or it will feel uncomfortable to have people with one racial, ethnic, or cultural background being directed by someone of another background.

Welcome emotions. Gently encourage people to openly express what they are feeling, recognizing that not all members of the group may feel comfortable opening up until the group has built more trust.

How to help people identify and talk about their feelings

Ask questions to help the group talk about feelings and how they affect us:

- What are the main feelings behind the experience just shared with us— what did we hear? For example, feeling sad, helpless, fearful.

- Are there social causes for those feelings? For example, if we were brought up to be ashamed of ourselves or to believe that asking for help shows weakness.

- How is the person coping with these feelings?

- What can we do to provide support?

When a person in the group shows distress

Support group discussions can stir deep feelings. As a person speaks about their thoughts or experiences, they may get very emotional. The group can help the person acknowledge and accept their feelings. The facilitator can say something like: “It’s OK, take the time you need, we’re here for you.” Or they can call on someone else and come back later to the person who was upset.

If a person expresses a more painful or uncontrollable emotion, it may be good to separate the person from the group and talk privately with them to check on their safety, evaluate if there might be a crisis, help them process their emotions, and ask about any other support they may need. You can also ask them if there is something they might want right now that the group can provide. This could be to hear supportive thoughts from others, receive hugs or prayers, decide to sit quietly for a while, or step out of the room to take care of themselves.

If the facilitator leaves the group to pay attention to the person in distress, ask another person to lead the group and check in on how everyone is feeling. The group could discuss the emotions, thoughts, or concerns the group member’s distress has brought up for them. Another strategy is to ask everyone to move to a new place in the circle. This literally changes people’s point of view and allows a reset.

When the person feels stable enough to participate again or rejoins the group:

- Let the group know what the person said would feel useful to them and limit the group’s response or support to that.

- Lead the group in a breathing, moving, or meditative exercise (see Regain calm and Pause and reset), or a song or prayer that can unify the group. Be sure to choose an activity that is acceptable to the distressed group member.

- Allow the group to move on naturally, discussing the topic at hand or moving on to another. If this member has a pattern of taking a lot of time and attention, it’s OK to openly invite the group to continue: “While David takes his time with this, let’s start again with others who are waiting to speak.”

- If the group becomes frustrated with the distressed member, it’s OK to lead a discussion about those feelings and dynamics. Instead of accusing or blaming them for doing something “wrong,” look for a way to have them reflect on what happened, such as: “Can you say more about how you expected us to react when you said that?” This way of “calling in” the person instead of just criticizing them can demonstrate care and an effort to repair the relationships while also building healthy expectations and boundaries for the group.

Activity

Pause and reset

This can be done individually or as a group. By stopping to relax for 1 to 5 minutes as a group, people can learn how this technique can be used anytime, on their own or when supporting others.

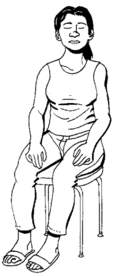

Sit comfortably, feet flat on the floor, hands resting in your lap.

Close your eyes. Ask yourself, “What am I thinking and feeling now?” Notice your thoughts and emotions, and how different parts of your body feel.

Listen to your breath as it goes in and out. Put a hand on your stomach and feel it rise and fall with each breath. Tell yourself, “It’s okay. Whatever it is, I am okay.” Continue to pay attention to your breath for a while and feel yourself become calmer.

Continue to pay attention to how your body feels and reflect on how you feel overall. Open your eyes and return to the situation, better able to cope.