Hesperian Health Guides

Developing your strategy for change

HealthWiki > Health Actions for Women > Chapter 10: Building a Women's Health Movement > Developing your strategy for change

Know your opponents, look for your allies

In Kamla, Ayesha, and Leela’s story, the 3 women hoped the health workers would be their allies, but were disappointed when the health workers ignored their problems.

Even if your goals are not controversial, people may oppose your ideas. For example, if you are part of a group that is working to open a youth clinic in a school, people might not support you because they:

- feel left out of the process. In this example, some parents and teachers may want to be involved but feel their opinions are not being heard.

- doubt the change that you propose is needed. For example, some doctors may not believe that youth need special health services, either because they don’t have the facts or because they don’t pay attention to anyone else’s point of view.

- feel that your goals conflict with local traditions and beliefs, or religious and moral values. For example, some parents and teachers may feel that making contraceptives available to young women will encourage them to be sexually active.

- feel that your goals threaten their livelihood, property, or social standing. For example, the owners of a pharmacy may oppose new health services if they believe they will lose business if young people can get free or low-cost medicines.

On the other hand, many people will support you because they feel strengthened and energized by your efforts. Your organizing could bring together many new allies who agree with your goals, as well as others who go along with it for practical reasons. People may support you because they:

- directly benefit from your goals. For example, students will be excited by the idea of a youth clinic with services they need and confidential care. They will support organizing efforts and will be happy that someone is stepping forward with confidence to make change.

- want to be a part of making change that matters. Health activists already involved in efforts to improve access to health care will support a youth clinic, as will others in the community who care about youth. They want to make the community and world a better place, and you are creating an opportunity for them to help.

- see the relationship between your goal and their own goals — even if the goals are different. For example, overworked nurses at the health center might see a school clinic as a way to ease their workload as well as improve everyone’s health. Supporting your organizing can help increase community awareness of the problems they face.

- see it could work in their favor. Sometimes a supporter may not even believe in your goal but sees how fighting on your behalf will bring other benefits. For example, the ministry of education staff may not agree with the need for a school-based clinic, but after seeing that health professionals, teachers, and parents support the proposal, they will support it to avoid controversy and gain a positive, problem-solving reputation.

A power map can help you make a strategy by identifying your allies and your opponents, as well as people who are neutral or undecided.

Activity

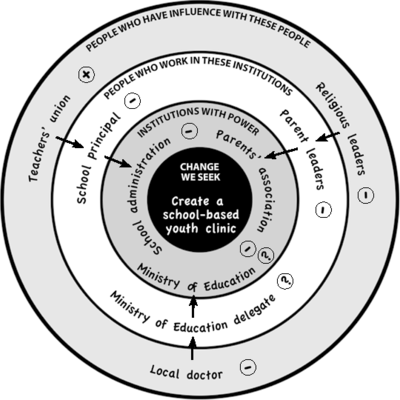

Make a power map

A power map can be used to strategize, to identify important allies, and to make a plan to work towards a specific goal. This example shows how a youth group working to improve health services for young people could use a power map.

This activity can be done over the course of several meetings so the group can collect information to bring back and add to the map.

- Write the change you seek in the middle of a large piece of paper, for example, "Create school-based youth clinic." Draw a circle around it.

- Identify the institutions with power to influence this change and write these around the circle. For example "School administration," "Parents’ Association," or "Ministry of Education." Draw a second ring around them.

- Think of a few people who are associated with these institutions and write down their names or titles — such as "School principal," "Parent leader," or "Ministry of Education delegate" — outside the circle. These are primary targets for your organizing work.

- Discuss whether these people support (+), oppose (-), or are undecided (?) about the change you seek. Put a +, -, or ? symbol next to their names or titles. Draw a third circle around these.

- Think about all the people who can influence the individuals who are opposed or are undecided, and write their names or positions in a new circle. For example, the youth group might write "Local physician," "Religious leaders," or "Ministry of Health delegate." These are secondary targets for your organizing work. Draw lines connecting these people to others they can influence.

- Discuss whether these people are supportive (+), opposed (-), or undecided (?), and write symbols next to their names.

- Carefully review the map of relationships. Ask the group to consider questions such as: Where are the allies (the people who are supportive)? How close are they to the institutions with power to influence the change we want to make? Where are the best opportunities for influencing key people in those institutions? It is also helpful to consider the benefits and risks of supporting your efforts for the different people and institutions on the power map. Understanding why they might oppose your efforts will help you develop a strategy to address challenges you might face.

- With the information you have collected, make a plan for gaining the support of allies who can help you influence the individuals and institutions you need on your side in order to achieve your goal.

Repeating the power map activity every few months is a good way to continue evaluating whether the strategy is working and to adjust your plans to include new allies.

Different strategies for organizing

When Kamla, Ayesha, and Leela started talking with each other about their health problems, they were taking the most important first step in organizing. They were breaking out of their isolation and also building a shared understanding of a problem they faced. Next, they confronted people at the health center and in the labor office — people who had the power to help them change their working conditions and their access to health services. As they worked with SEWA, they discovered various strategies they could use to achieve their goal.

Build consensus. If politicians and health workers are cooperative and receptive, a group might try to build consensus to make changes that everyone can agree on without conflict. This tends to be easier than other approaches, but it only works if everyone already agrees about what changes are necessary. Kamla, Ayesha, and Leela tried to build consensus with the health workers at the clinic and also with the state labor office, but they found they could not. Instead, they had to pressure them into listening — also known as "taking power."

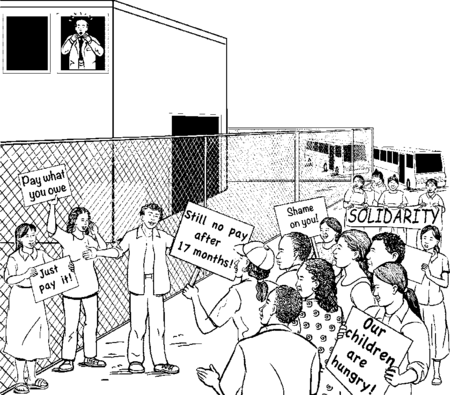

Take power. Sometimes a group may need to take some power away from those who control decisions. They do this by using collective strength and public action to force those in power to give in. How does this work? Why would people in power give up some or all of their control over what happens? Often, those in power will shift their position, not because they have been persuaded by a moral argument, but because public pressure has left them no other choice. They realize that the cost to them of not giving in is greater than the cost of giving in. When Kamla, Ayesha, and Leela went to the state labor office, officials there lost nothing by turning them away. But when a large group of well-organized women showed up and made it clear they would not just go away, the labor secretary gave up some of his power. He accepted their demand, and the women gained power.

Make power. Even when excellent organizing manages to build consensus or take power, there are some situations where groups need to create a whole new structure outside of official channels. Although the SEWA women had forced the labor secretary to support their struggle, and although the health workers were now paying attention to work-related injuries and health issues, poor women in Ahmedabad still could not afford medicine. As organizers, they needed a strategy. They could try to build consensus with pharmaceutical companies by asking them to lower their prices. They could try to take power from those companies by forcing them to lower their prices. Or they could make power by creating an entirely different structure — a cooperative that could buy cheaper medicines in bulk and distribute them fairly.

Organizing to challenge public opinion about health services (or anything else) may cause a backlash — an organized campaign by your opponents to destroy your group and your goals. By building a new consensus, by aiming to take power from individuals and institutions, or by figuring out ways to make new power, you may face resistance, stigma, personal risks, or even physical threats. This can be very stressful and exhausting for the group and for each person involved. Often, however, people become even more committed, more united, and more creative in response.

Even if the struggle is not so difficult, people change as they get involved in organizing. They develop new relationships, new insights into their own power, and new ideas about what is possible. As you win (and sometimes lose) the various battles you choose to engage in, you also help to create the conditions for more and deeper change.