Hesperian Health Guides

Building a movement for the right to health

HealthWiki > Health Actions for Women > Chapter 10: Building a Women's Health Movement > Building a movement for the right to health

The next section shares some examples of strategies people from around the world have used to defend the right to health for all.

Contents

Hold governments accountable

Governments are responsible for ensuring that the rights of their citizens are respected. In many places, governments are also legally responsible for providing health care and other basic services, such as water and sanitation. Holding governments accountable for defending people’s rights and providing health care and other basic services can be a main focus of organizing.

Community health committees

In many countries, organizers have fought for and won the right to create community health committees. These committees often work with governments and health centers to decide what health projects should be funded. They may also help raise money for specific projects, such as training in health promotion. A health committee can evaluate the services a health center provides and offer feedback from the community. For example, a health committee might evaluate whether a death might have been prevented, respond to community complaints against a health center, and when needed hold the health center accountable.

A health committee should include community members who represent different experiences and opinions, especially those whose voices are not usually included in formal discussions about the way things that affect everyone in the community are done. It is important to set up a process for shared decision making among community members, health center staff, and other stakeholders to avoid struggles over who has the power to address complaints about the health services and to make decisions. One way to make sure everyone participates is to create ways for more experienced members of the committee to mentor those with less experience. Community members, including youth, need to learn how health systems and budgets work, so they can fully participate in decision making.

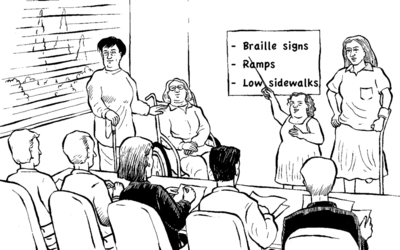

Disability activists design a more accessible city

In Ekaterinburg, Russia, city officials developed a disability program to make buildings more accessible. But a group of people with disabilities realized that even though the government had been trying to help, many of the places they had changed were still hard for disabled people to use. So they formed the Freedom of Movement Society and met with city officials to give them a list of ways to make the city more accessible. The city officials allowed members of the group to join the city planning committee and had them design guidelines that architects could use to make buildings accessible.

Social audits

A social audit is a public evaluation of how well services, such as health care or education, are meeting the needs of the people they serve. A social audit can be a good way to make problems visible, generate media coverage, and develop demands for improvements. A social audit usually involves collecting information through interviews or surveys, and sharing the results publicly. Questions might include: Does everyone receive the same quality of care? Do the services offered meet all people’s needs? How are funds being used? Are essential medicines and supplies available?

If they are willing to participate, representatives from health center staff and local authorities can join community organizations to conduct a social audit.

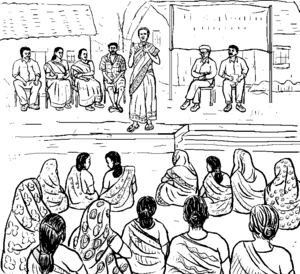

Here is an example of a campaign using one type of social audit in India.

People’s Health Tribunals improve health services in India

A group of “lower-caste” women in Bangalore, India, were angry when they

learned that their local health center received government money for basic health

services that were not being provided. They joined with other activists and used a

checklist to document the services and medicines offered, the hours the center was

open, and what equipment was in use.

The campaign the women had joined, Jan Swasthya Abhiyan (JSA), then organized a People’s Health Tribunal. Sympathetic experts and allies acted as a panel of "judges" and listened to testimony about how people’s right to health had been violated. The women were proud and excited to be called as witnesses at the Tribunal and speak in front of nearly 1,000 people about what they found in the audit of their health center and their experiences of being denied care. Sharing their experiences and hearing the testimonies of other activists made them feel stronger and able to continue to demand improvements from the local health center.

During the next two years, People’s Health Tribunals were held in many parts of India. Then the JSA activists shared all the documentation they had collected with the Indian National Human Rights Commission. The Commission was convinced that the denial of health care was a critical human rights issue. With the Commission’s help, more than 100 JSA delegates and other experts testified in a public hearing with the national health minister and senior government officials. The hearing concluded with a declaration recognizing the right to health of all Indian citizens and a recommendation to increase the government health budget to ensure quality health care for all Indians.

While many changes have yet to be put into practice, the work of the women from Bangalore has already improved health care in India and has also inspired others. Health activists around the world have convened People’s Health Tribunals to examine violations of people’s rights from lack of health services, the devastating health effects of the mining and oil industries, and poverty wages paid to women workers in garment factories.

Budget accountability

Monitoring how public funds for health care are actually spent in your local clinic is another part of a social audit. Public discussion of how funding priorities are decided, and then whether the government allocates enough money for them, also holds governments accountable for supporting everyone’s right to health.

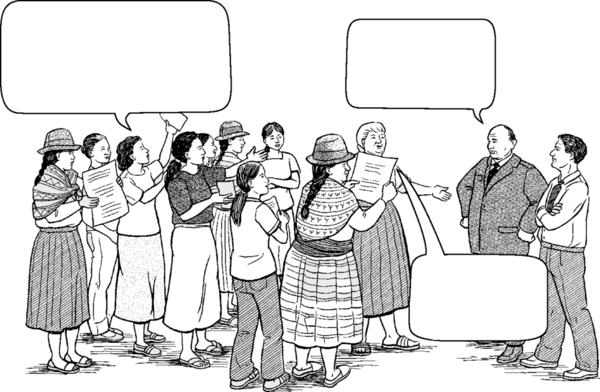

The organizing work of the community members in Vilcashuamán, Peru, in Chapter 2 is an example of successful organizing to have government funds permanently allocated for women’s health. Their organizing efforts helped others learn about the Peruvian health budget.

Learning about health budget leads to change in Peru

Women in another isolated community in Peru, hundreds of miles away, learned about the work of Vilcas Women’s Voices through radio shows and other networks. They learned they could get information on the Internet about how government funds should be spent. They discovered that even though their community was supposed to receive funds for women’s health services, the local health center did not provide those services. These women organized a march to the mayor’s office to demand more support for women’s health.

Since then, this group has been able to hold local leaders accountable, and the health center has provided more health services for women.

Protect public health services

Organizing to improve health for women involves fighting discrimination, poverty, and government policies that do not prioritize the needs of women and girls. Often, it also involves fighting government policies that allow private companies to take over and profit from the basic services everyone needs to live and be healthy. In many countries — both rich and poor — governments have stopped providing health care, water, electricity, and other services. Instead, private companies have taken over these services even though they were built with public funds. This is called privatization.

Unlike governments, private companies are not accountable to the people they are supposed to serve and they do not allow women and men in the community to have a say in the way services are provided. Instead, companies charge as much as they can for services and they stop providing services that are not "profitable," no matter how important or needed they may be.

Privatization allows the already rich to make even more profit while the health of poor women and their children suffers most of all.

Doctors advocate for people’s health:

The marchas blancas ("white marches") in El Salvador

In El Salvador, health workers have struggled to improve health services for everyone. Since the end of the civil war in 1992, health worker unions and their allies have resisted health care privatization, while fighting for health reforms and improved access to medicines.

In late 2002, public health system doctors and nurses went on strike to resist privatization of the public health system. Privatization occurs when governments pay private companies to provide services the government previously provided, or when the government sells off state property, such as schools or hospitals, to private companies. Some hospitals had already been partly privatized, and political pressure from the wealthy tried to force the government to contract private companies to run most of the health system. Although health care privatization was new in El Salvador, health care workers and patients knew what to expect. During the previous decade, the government-run energy and communications sectors were privatized, making services more expensive. Because of this experience, activists expected that private health care would cost more and reach fewer poor people compared to government-run services.

In response, the health care workers organized huge "white marches" where health care workers — many of them women — protested in their white coats and uniforms. Allies from peasant, student, labor, and women’s organizations at the marches also wore white in solidarity. Women’s groups were particularly active because they knew how important quality health care was for women and that the health workers supported women’s rights. The protest continued for 9 months with marches, vigils, roadblocks, and sit-ins all around the country. After that, the health care unions and the government signed an agreement that ended the privatization process.

Five years later, a major breakthrough occurred when a new political party came into power. The Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN in Spanish) won the presidency, partly because of their popularity with groups fighting against privatization. With this support, the FMLN government reformed health care to increase access and quality for most of the population. They also passed a law that made medicines less expensive by breaking private corporations’ control of distribution and sales. This was all possible because of the years of educating, organizing, and protesting by health workers and their allies to defend the right to health care.

Support the struggle for health for all

Access to food, water, housing, education, safe and fairly paid work, and freedom from discrimination are conditions we all need in order to be healthy. They are also human rights and the foundations of a just society. International declarations and laws have recognized these as rights for all people. Regardless of the color of their skin, of whether they are from a poor or wealthy family, or live in a poor or wealthy country, all women and girls have the right to live healthy and productive lives.

Access to health care that meets all people’s needs is recognized as a human right. All women and girls have the right to health care that is available and affordable, that honors their traditions, and that meets their needs.

There are many ways to organize to improve women’s health and access to health care. The women of Vilcashuamán, Peru (Chapter 2) wanted to reduce the number of indigenous women who die in childbirth. They achieved this by setting goals and strategy, patiently developing allies, and constantly evaluating and learning from their work. The three women from Ahmedabad, India (Chapter 10) wanted to receive care for their workrelated health problems. They achieved this by joining with a grassroots organization, SEWA, and working with them to build alliances with government labor officials, occupational health experts, health workers, and other working women.

Many efforts are described in this book, including communities re-examining gender roles, young people raising awareness about sexual health, artists using puppets to educate and mobilize people around HIV prevention, and neighbors figuring out how to make their communities safer from gender-based violence. These represent only a small fraction of the organizing efforts going on around the world!

In each of these efforts, people joined together to make change, built new leadership from the ground up, and developed connections and knowledge that will make them stronger in future struggles. They faced challenges and even threats, but by staying committed to their goals they saved lives, improved the health of many, and made their communities more just and equitable.

By sharing ideas and experiences, and failures and successes, the work of these organizers also has had a ripple effect — informing, inspiring, and supporting others. They may live close by in the same community, or far apart on the same planet. Women and men of all ages have become part of a diverse and widespread movement for the Right to Health for all. They — and we — invite you to join us.