Hesperian Health Guides

Training

Contents

The integrated approach

When possible, it is usually best that skills training for people with disabilities take place together with skills training for people without disabilities. For example:

- A child with disabilities can go to the river to learn to wash clothes with other children and adults.

- A child with disabilities can go to the fields to help plant, weed, and harvest alongside his family.

- A child with disabilities can go to the same school as other children, and then go on to some specialized training course.

- A young person with disabilities may enter a shop or production team as an apprentice just as young people without disabilities often do.

|

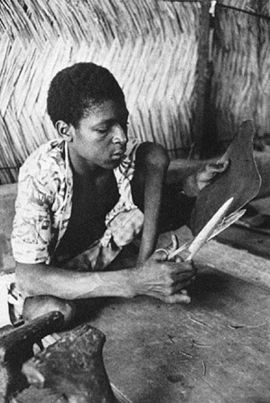

| This young man in Niger, Africa, learned to make leather goods together with other young people with disabilities. Later he can work out of his own home and sell his goods in the marketplace. (Photo: Carolyn Watson) |

For a child with mild to moderate disabilities, there are many possibilities to prepare for life’s work together with other children—especially if parents encourage the child and explore opportunities. A community rehabilitation program can help by encouraging schoolteachers, schoolchildren, training program instructors, craftspersons, and possible employers to be more open to giving young people with disabilities an equal chance.

For young people with more severe disabilities, opportunities for integrated education or skills training will be much more limited. Alternatives need to be looked for, or arranged, especially in communities that are still not open to giving them an equal chance.

Special training possibilities

Different approaches have been tried to help people with disabilities learn specific skills. In cities, training centers are sometimes set up for children with similar disabilities. These include programs for children with hearing or vision loss and centers for young people with cognitive delay. Each program chooses skills and activities suited to the particular limitations and abilities of the group. For example, a skills training and production program for people with vision loss may focus on skills that depend largely on touch, such as weaving or chalk making.

In smaller villages, it is often not possible to bring together enough persons with the same kind of disability to create a specialized training program just for them. However, a community rehabilitation program can, in its workshop, include a variety of skills training opportunities which can be adapted to persons with a wide range of disabilities.

Sheltered workshops —yes or no?

Sheltered workshops are training and production centers specifically for people with disabilities. The idea is to provide a work opportunity and a little pay to those who would find it difficult to get training and employment in other places.

At best, these workshops can be a very valuable experience for participants, and may serve as a step toward greater independence. They help participants gain the technical and social skills, work habits, responsibility, and self-confidence needed for outside employment or self-employment.

At worst, sheltered workshops can (and often do) actually hold back the development and crush the spirit of participants. Too often they are run by persons who treat the workers like babies or slaves, giving them simple, repetitive tasks. The workers are not involved in the planning, organization, or running of the program. They are simply told what to do. They become increasingly dependent on the center and fearful of their inability to make it on their own in the outside world.

Perhaps the key difference between these two kinds of sheltered workshops is the question of control and equality. If the participants are involved in the direction and decision making of their own program, then they will grow and mature along with the program. Perhaps they will make more “mistakes” than a program that is controlled and run by “superiors.” But they will learn from those mistakes. At the same time they learn crafts, they learn skills in decision-making, problem-solving and small-group democracy—essential skills for improving life in the “real world.”

A community-based rehabilitation program run by people with disabilities may have some features of a sheltered workshop. It may provide special training and work opportunities adjusted to the pace, abilities, and limitations of each participant. It may provide such an enjoyable home and family setting that some persons may choose to keep working rather than to move on into the “outside world.” But because it is a program run by people with disabilities, and major decisions are made at all-group meetings, it tends to be a dignifying and liberating experience.

A program where people with and without disabilities work side by side, sharing equally in decisions and responsibility, may be even more liberating.

Children with paralysis in their bodies often develop strong arms and hands—and can do many kinds of work.

|

|

| Here 2 boys who had polio build cane blinds for the model home at PROJIMO. | This boy with paraplegia from tuberculosis spokes a wheel for a wheelchair. He rides a wheeled lying board because of pressure sores on his butt. |

Combining work with therapy

Whenever possible, look for work that will help a person with disabilities fit into the life of their community, and that will also provide needed exercise or therapy. Here is one example from the Sarvodaya community-based rehabilitation program in Beruwala, Sri Lanka.

| With the help of her family and a village rehabilitation volunteer, this girl with cerebral palsy learned to make rope from coconut fiber (jute). This is a common village craft, so she can work with other villagers. | |

|

|

| Separating and preparing the fibers is good therapy for the spasticity in her hands. | Twisting the fiber with this wheel to make rope helps her move her stiff arms in a smooth circle—providing excellent, active therapy while she works. |