Hesperian Health Guides

Early Questions That a Spinal Cord Injured Child and Family May Ask

HealthWiki > Disabled Village Children > Chapter 23: Spinal Cord Injury > Early Questions That a Spinal Cord Injured Child and Family May Ask

“Will my child always remain paralyzed?”

| It is very unusual that a child who is paralyzed by a broken neck is walking with a neck collar in 6 weeks. |

|

This will depend on how much the spinal cord has been injured. If paralysis below the level of the injury is not complete (for example, if the child has some feeling and control of movement in her feet) there is a better chance of some improvement.

Usually the biggest improvement occurs in the first months. The more time goes by without improvement, the less likely it is that any major improvement in feeling or movement will occur.

Occasionally surgery to release pressure on the spinal cord or nerves, if done in the first hours or days following the injury, will bring back some movement or feeling. But surgery done more than a month after the injury almost never brings back any movement or feeling. Never agree to such surgery unless at least 3 independent and highly respected neurosurgeons recommend it.

After one year, the paralysis that remains is almost certainly there to stay. As gently as you can, help both the child and parents accept this fact. It is important that they learn to live with the paralysis as best they can, and not wait for it to get better or go from clinic to clinic in search of a cure.

It is best to be honest with the child and the family. Explain the facts of the situation as clearly, truthfully, and kindly as possible.

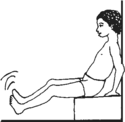

CAUTION! Sudden jumping or stiffening of the legs when moved or touched does not mean feeling or controlled movement is returning. This is a reflex characteristic of spasticity.

“My child’s feet are beginning to move!”

Immediately after a spinal cord injury the paralyzed parts are in “spinal shock,” and are loose or floppy. Later (within a few days or weeks) the legs may begin to stiffen—especially when the hips or back are straightened. Also, when moved or touched, a leg may begin to “jump” (a rapid series of jerks, called “clonus”).

This stiffening and jerking is an automatic reflex called “spasticity.” It is not controlled by the child’s mind, and often happens where spinal cord injury is complete. It is not a sign that the child has begun to feel where he is touched or is recovering control of movement.

| Some children with spinal cord injury develop spasticity; others do not. | Severe spasticity often makes moving and control more difficult. However, the child may learn to use both the reflex jerks and spastic stiffness to help her do things. For example, | |

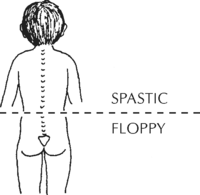

level between 1st and 2nd lumbar vertebrae

If the spinal cord injury is above the level of the top edge of the hipbone (above the 2nd lumbar vertebra) spasticity is very likely.

If the injury is below this level, paralysis is usually floppy (no muscle spasms). |

|

|

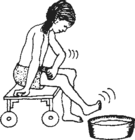

| When the child wants to lift her foot, she hits her thigh, triggering the jerks that lift the leg. | In lower back injuries, the spasticity or stiffness of the legs may actually help the child stand for transfers. | |

“Will my child be able to walk?”

Catch me if you can! |

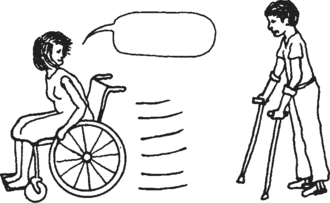

| Many people with spinal cord injuries prefer a wheelchair to walking with braces and crutches. |

This will depend mostly on how high or low in the back the injury is. The lower the injury, the better the chance of walking. A person with complete spinal cord injury in the neck has no chance of walking. She will need a wheelchair.

If the child’s injury is in the lower back and if his arms are strong, there is a chance he may learn to walk with crutches and braces. But he will probably still need a wheelchair to go long distances.

However, it is best not to place too much importance on learning to walk. Many children who do learn to walk find it so slow and tiring that they prefer using a wheelchair.

For most children with paraplegia, it probably makes sense to give them a chance to try walking. However, do not make the child feel guilty if he prefers a wheelchair. Let the child decide what is the easiest way for him to move about.

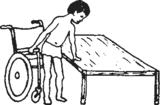

For independent living, other skills are more important than walking, and the family and child should place greater importance on these: skills like dressing, bathing, getting into and out of bed, and toileting. Self-care in toileting is especially important—and is more difficult because of the child’s lack of bladder and bowel control.

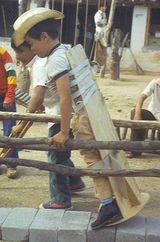

| A child who is paraplegic learns to walk with a plywood parapodium made by village rehabilitation workers. (PROJIMO) |  |

“What are the hopes for my child’s future?” The chances of a person with paraplegia leading a full and happy life are good—provided that you:

-

avoid 3 big medical risks:

- skin problems (pressure sores)

- urinary infections

- contractures (shortening of muscles, causing deformities). (Contractures are not a danger to life but can make moving about and doing things much more difficult.)

-

help the child to become more self-reliant by providing:

- home training and encouragement to master basic self-help skills such as moving about, dressing, and toileting

- education: learning of skills that make keeping a household, helping other people, and earning a living more possible

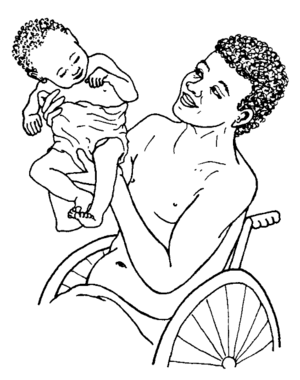

It is more difficult for people with quadriplegia to live independently because they are more dependent on physical assistance. However, in some countries many people with paraplegia and quadriplegia manage to lead full, rich lives, earn their own living, get married, and play an important role in the community. With effort and organization, the same possibilities can exist in all countries.

“Can anything be done about loss of bladder and bowel control?”

Yes. Although this control rarely returns completely, the child with a spinal cord injury often can learn to be independent in his toilet, and to stay clean and dry (except for occasional accidents). Often he will need a urine collecting device, will learn to use a catheter, and will learn to bring down a bowel movement with a finger or suppository. Management of bladder and bowels is discussed in Chapter 25.

VERY IMPORTANT INFORMATION ON URINE AND BOWEL CONTROL IS IN CHAPTER 25. BE SURE TO READ THIS CHAPTER!

“What about marriage, sex, and having children?”

Many people with spinal cord injuries enjoy loving, sexual relationships, and if they want to, marry. Women with spinal cord injuries can become pregnant and have children. Men with paraplegia and quadriplegia whose injuries are incomplete are more likely to be able to get a hard penis or ejaculate (release sperm) and have children than those whose injuries are complete. Some couples decide to adopt children.

Especially for young men, fear of the loss of sexual ability is often one of the most fearful and depressing aspects of spinal cord injury. Honest, open discussion about this, and the possibilities that do exist, with a more experienced person with spinal cord injury may help greatly. There is a good discussion of this in Spinal Cord Injury Home Care Manual.