Hesperian Health Guides

About This Book

Contents

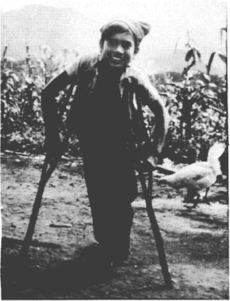

A TRUE STORY: CRUTCHES FOR PEPE

A teacher of village health workers was helping as a volunteer in the mountains of western Mexico. One day he arrived on muleback at a small village. A father came up to him and asked if he could cure his son. The health worker went with the father to his hut.

The boy, whose name was Pepe, was sitting on the floor. His legs had been paralyzed by polio, from when he was a baby. Now he was 13 years old. Pepe smiled and reached up a friendly hand.

The health worker, who also had a physical disability, examined Pepe. “Have you ever tried to walk with crutches?” he asked. Pepe shook his head.

“We live so far away from the city,” his father explained.

“Let’s try to make some crutches,” said the health worker.

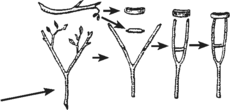

The next morning the health worker got up at dawn. He borrowed a long curved knife and went into the forest. He looked and looked until he found 2 forked branches the right size.

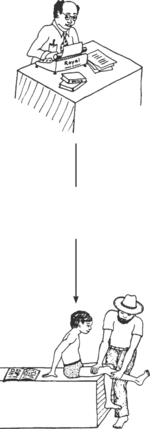

He took the branches back to Pepe’s home and began to make them into crutches, like this.

The father came and seeing the crutches, he said, “They won’t work!”

The health worker frowned. “Wait and see!” he said.

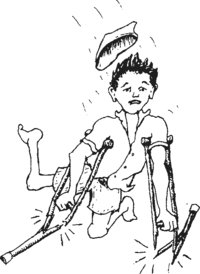

When both crutches were finished, they showed them to Pepe, who was eager to try them. His father lifted Pepe to a standing position and the health worker placed the crutches under the boy’s arms.

But as soon as Pepe put his weight on the crutches, they bent and broke.

“I tried to tell you they wouldn’t work,” said the father. “It’s the wrong kind of tree. Wood’s weak as water! But now I see your idea. I’ll go cut some branches of ‘jutamo’. Wood’s tough as iron, but light! Don’t want the crutches too heavy.”

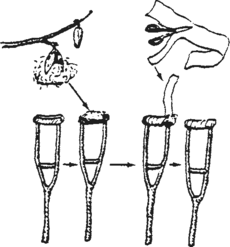

He took the knife and went into the forest. Fifteen minutes later he was back with 2 forked branches of ‘jutamo’. He began making the crutches, his strong hands working rapidly. The health worker and Pepe helped him. “I tried to tell you they wouldn’t work,” said the father. “It’s the wrong kind of tree. Wood’s weak as water! But now I see your idea. I’ll go cut some branches of ‘jutamo’. Wood’s tough as iron, but light! Don’t want the crutches too heavy.” He took the knife and went into the forest. Fifteen minutes later he was back with 2 forked branches of ‘jutamo’. He began making the crutches, his strong hands working rapidly. The health worker and Pepe helped him.

When these crutches were finished, Pepe’s father tested them by putting his own weight on them. They supported him easily, yet were lightweight. Then Pepe tried them. At first, he had trouble balancing, but soon he could hold himself up. By afternoon, he was walking with the crutches! But they rubbed under his arms.

“I have an idea,” said Pepe’s father. He ran to a wild kapok tree, and picked several of the large ripe fruits. He gathered the soft cotton from the pods and put a cushion of kapok on the top crosspiece of each crutch. He wrapped the kapok in place with strips of cloth. Pepe tried the crutches again. They were comfortable.

“Thanks. Papa, you fixed them great!” he said, smiling at his father with pride. “Look how well I can walk now!” He moved about quickly in front of them.

“I’m proud of you, son!” said his father, smiling too.

As the health worker prepared to leave, the whole family came to say good-bye.

“I can’t thank you enough,” said Pepe’s father. “It’s so wonderful to see my son walking. I don’t know why I never thought of making crutches before...”

“I should be thanking you,” said the health worker. “You have taught me a lot.”

After leaving, the health worker smiled to himself. He thought, “How foolish of me not to have asked the father’s advice in the beginning. He knows the trees better than I do. And he is a better craftsperson.

“But it was good that the crutches I made broke. Making them was my idea, and the father felt bad for not thinking of it himself. But when my crutches broke, he made much better ones. That made us equal again!

So the health worker learned many things from Pepe’s father—things that he had never learned in school. He learned what kind of wood is best for making crutches. He also learned how important it is to use the skills and knowledge of the local people—because a better job can be done, and because it helps maintain people’s dignity. People feel equal when they learn from each other.

HOW THIS BOOK WAS WRITTEN

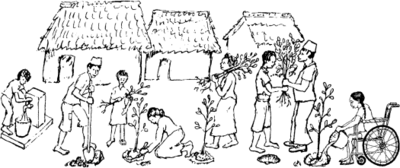

The story of Pepe’s crutches is an example of the lessons we have learned that helped to create this book. We are a group of village health and rehabilitation workers who have worked with people in farming communities of western Mexico to form a villager-run rehabilitation program. Most of us on the rehabilitation team have disabilities ourselves.

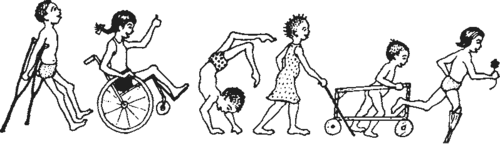

From our experience of trying to help children with disabilities and their families to meet their needs, we have developed many of the methods, aids, and ideas in this book. We have also gathered ideas from books, persons, and other programs, and have adapted them to fit the limitations and possibilities of our village area. We hope this book will be useful to village people in many parts of the world. So we have asked for cooperation and included suggestions from community program leaders in more than 20 countries.

HOW THIS BOOK DIFFERS FROM OTHER REHABILITATION MANUALS

This book was written from within the communities it serves, working closely with people with disabilities and their families. We believe that those with the most personal experience of disability can and should become leaders in resolving the needs of the disabled community. In fact, the main author of this book (David Werner) and many of its contributors happen to have disabilities. We are neither proud nor ashamed of this. But we do realize that in some ways our disabilities contribute to our abilities and strengths.

| Instead, it was written by and with community workers, | and then reviewed by rehabilitation professionals. |

| |

In many rehabilitation manuals, people with disabilities are treated as objects to be worked upon, to be made as “normal” as possible. As people with disabilities, we object to attempts by the experts to fit us into the mold of “normal”. Too often “normal” behavior in our society is selfish, greedy, narrow-minded, prejudiced, and cruel to those who are weaker or different from others. We live in a world where too often it is acceptable for the rich to live at the expense of the poor, and for health professionals to earn many times the wages of those who produce their food but cannot afford their services. We live on a planet which produces enough food for everyone but where many people go hungry. Where half of all people are denied access to the health care they need. Where the world's leaders spend trillions of dollars every year on instruments of war instead of meeting people's needs.

Instead of being “normalized” into such an unkind, unfair, and unreasonable social structure, we people with disabilities would do better to join together with all who are treated unfairly, in order to work for a new social order that is kinder, more just, and more sane.

This large book, then, is a small tool in the struggle not only for the liberation of people with disabilities, but for their solidarity in the larger effort to create a world where more value is placed on being human than on being “normal”, a world where war and poverty and despair no longer disable the children of today, who are the leaders of tomorrow.

Rehabilitation manuals too often only give orders telling the local trainer, family member, and person with disabilities exactly what they must do. We feel that this is a limiting rather than liberating approach. It encourages people to obediently fit the child into a standard rehabilitation plan, instead of creating a plan that fits and frees the child. Again and again we see exercises, lessons, braces, and aids incorrectly, painfully, and often harmfully applied. This is done both by community rehabilitation workers and by professionals, because they have been taught to follow standard instructions or prepackaged solutions rather than to respond in a flexible and creative way to the needs of the whole child.

In this book we try not to tell anyone what they must do. Instead we provide information, explanations, suggestions, examples, and ideas. We encourage an imaginative, adventurous, thoughtful, and even playful approach. After all, each child is different and will be helped most by approaches and activities that are lovingly adapted to her specific abilities and needs.

As much as we can, we try to explain basic principles and give reasons for doing things. After village rehabilitation workers and parents understand the basic principles behind different rehabilitation activities, exercises, or aids, they can begin to make adaptations. They can make better use of local resources and of the unique opportunities that exist in their own rural area. In this way many rehabilitation aids, exercises, and activities can be made or done in ways that integrate rather than separate the child from the day-to-day life in the community.

This is not the first handbook of “simplified rehabilitation”. We have drawn on ideas from many other sources. We would like to give special credit to the World Health Organization’s manual, Training the Disabled in the Community, and to UNICEF and Rehabilitation International’s Childhood Disability: Prevention and Rehabilitation at the Community Level, a shortened and improved version of the WHO manual. The WHO manual has recently been rewritten in a friendlier style that invites users to take more of a problem-solving approach instead of simply following instructions.

This handbook is not intended to replace these earlier manuals. It provides additional information. It is for families, community members, village health workers, and community rehabilitation workers who want to do a more complete job of meeting the needs of children with disabilities.

WHICH DISABILITIES WE INCLUDED IN THIS BOOK

It is difficult to estimate how many of the world’s children have disabilities. Disability is defined and measured differently among countries. And how much a condition impacts a child’s ability to lead a full, active life can depend on where that child lives. The World Health Organization estimated in 2004 that 1 in 20 children 14 years old or younger live with a moderate to severe disability.

Local beliefs also affect how people see disabilities. In an area where people believe that seizures are the work of the devil, a child with seizures may be feared, teased, or kept hidden. But in places where everyone accepts seizures as “just something that happens to certain persons,” a child who sometimes has seizures may participate fully in the day-to-day life of the community, without being viewed as having a disability. It is important to consider how local people see a child who is in some way “different.” How do they accept or treat the child who takes longer to learn, limps a little, or occasionally has seizures? If the community does not consider a child “disabled,” and the child is able to live a happy and fulfilling life there, it may be better not to bring attention to her condition. To do so may actually make life harder for her.

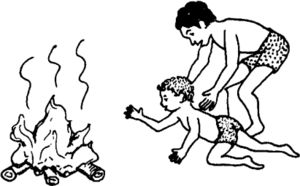

This book is written for use in many countries, and people in different parts of the world give importance to different disabilities. This is partly because some disabilities are much more common in some places. Hearing loss and cognitive delay are more common in areas where the local diet is low in iodine. Problems seeing due to lack of vitamin A is common in communities with limited access to animal sources of food, and where children are frequently sick during childhood. Rickets is still common in regions where foods rich or fortified in vitamin D are not available, and there is limited skin exposure to sunlight due to geography, climate, and/or cultural practices. Burn injuries are frequent where people cook and sleep on the ground near open fires.

In communities affected by HIV, many children are born to HIV-infected mothers. When parents and babies are treated for HIV, children can survive and live with HIV (and many avoid getting HIV at all). This book does not separately address illness and disability related to HIV, but many of the sections will be useful for children with HIV (assistive walking devices, child development, care for pressure sores, etc.). For more information, see Helping Children Live with HIV or a general health book like Where There Is No Doctor.

|

|

|

| A child with cognitive delay and typical physical development, | may not be as affected by their disability in a village, | but may be very affected in a city or a school. |

|

|

|

| A child with physical disabilities who has typical cognitive development, | may be very affected by their disability in a village, | but may not be as affected in a city or in school. |

This is understandable. In poor farming communities, where many day-to-day activities depend on physical strength, and where schooling for most children is brief, the child with physical disabilities can have an especially difficult time fitting in. By contrast, in a middle-class city neighborhood, where children are judged mainly by their ability in school, it is the child with cognitive delay who often has the hardest time.

The team of village workers with disabilities in Mexico was at first concerned mostly with physical disabilities. But they soon realized that they also had to learn about other disabilities. Even children whose main disability was physical, like paralysis, were often held back by other (secondary) emotional, social or behavioral disabilities. And many children with brain injury not only had difficulties with movement, but also took longer to learn, had seizures, or could not see or hear.

As the PROJIMO team’s need for information on different disabilities has grown, so has this book. The main focus is still on physical disabilities, which are covered in more detail. However, the book now includes a fairly complete (but less detailed) coverage of cognitive and developmental delay. Seizures (epilepsy) are also covered. Loss of vision and loss of hearing are included, but only in a very brief, beginner’s way. This is partly because we at PROJIMO still do not have much experience in these areas. And partly it is because seeing and hearing disabilities require so much specific information that they need to be covered in separate books. Hesperian has since produced good instructional material on these disabilities. We list some of the best materials that we know in Other Resources.

Note: This book does not include disabilities which are mainly in the area of internal medicine, such as asthma, chronic lung or heart problems, severe allergies, diabetes, bleeding problems, cancers or HIV. And except for brief mention, it does not include very local disabilities such as lathyrism (parts of India). In local areas where such disabilities are common, rehabilitation workers should obtain information separately.

To decide which disabilities to put in this book and how much importance to give to each, we used information from several sources, including the records of Project PROJIMO in Mexico. We found that the numbers of children with different disabilities who came to PROJIMO were fairly similar to those in studies done by WHO, UNICEF, and others in different areas of the world.

HOW THE COMMUNITY VIEWS PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

A disability is a condition that causes a person to move, see, hear, learn, or understand differently from people without disabilities. A person’s disability, in combination with their environment, may make it more challenging for them to live their daily life. In many places, people with disabilities are ill-treated, bullied and discriminated against because of their disability. They are thought of as “different” or “other.” Sometimes, they are considered “not quite human.” This discrimination may come from negative feelings and beliefs about disability expressed by people from within their community or their family. Often, people with disabilities have their own attitudes and beliefs about their disability which can cause them to think of themselves in the same way that their community views them. In some cultures, people believe that disabilities are caused by curses, are the result of bad behavior by a person or their family, or are contagious. As a result, people with disabilities may be denied opportunities to receive education or training, and to participate socially in their community. Their families may become isolated, limiting their access to community support as well as jobs and income. This can have lasting physical and emotional effects on people with disabilities and their families.

It is essential to work together to understand disabilities, the experiences of people living with disabilities, and to struggle against incorrect views and ideas about them. It is also important to find ways to bring greater understanding and acceptance of people with disabilities within the cultural reality of a community. No doubt this will be done in different ways in different places. For ideas about bringing greater understanding of the needs of people with disabilities to their communities, see Chapter 44.

Language changes a lot as time passes. How we talk about disability changes as we understand more about the causes of disabilities, and how the words we use affect the people who experience them. You might notice that the words we use in this book to talk about specific disabilities, or disability in general, are not words you are familiar with. This may be because different words are used in different places in the world, or it may be because the language around disability has changed.

In this book, we talk about “children with disabilities” rather than “disabled children” (although the title of the book remains the same), because it is important to put the person first, not the disability. We try not to make assumptions about the lives of people with disabilities, so we talk about people “experiencing” disabilities rather than “suffering from” them. We have been mindful of language that would suggest that people with disabilities are less valuable or less important than people without disabilities. If there are places where our language still needs work, please let us know.

Literature on children with disabilities often speaks of the disabled child as “he.” This is partly because male dominance is built into our language. It is also because boys with disabilities often receive better attention than do girls with disabilities. This is not surprising since, in many countries, boys without disabilities also get better treatment, more food, and more opportunities than girls without disabilities.

Because this adds to the continued oppression of children who are already disadvantaged, we have taken a different approach in this book.We sometimes refer to the child as “she,” and sometimes as “he,” and sometimes as “they.” We apologize if at times this is confusing. And if we sometimes slip and give more prominence to “he” than “she” or “they,” either in words or pictures, please let us know. We are working to change.

This book is a group effort. Although one person did most of the writing of this book, many shared in its creation and have contributed to its continued existence (see the “Thanks” page at the beginning of this book). Therefore, when speaking from the viewpoint of our authors and advisors, we usually use “we.”

|

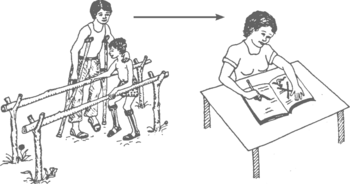

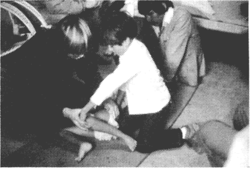

| A visiting therapist at PROJIMO teaches the older brother of a girl with disabilities how to do stretching exercises of her hip to correct a contracture. |

Villagers are often much better than city persons at figuring out how to do things, at using whatever happens to be available, and at making and fixing things with their hands. In short, they are more resourceful. They have to be to survive! This resourcefulness of village people can be one of the most valuable resources for rehabilitation in rural areas.

But for this to happen, we need to help people understand basic principles and concepts, not just tell them what to do. Above all, we need to respect their intelligence, their knowledge of the local situation, and their ability to improve on our suggestions.

Whenever possible, arrange for village workers to learn to use this book with guidance from experienced rehabilitation workers. Those rehabilitation workers should be able to listen to the people, respect their ideas, and relate to them as equals.

For best learning, the teacher or guide should stay as much in the background as possible, offering friendly advice when asked, and always asking the learners what they think before giving instructions and answers.

It is our hope that this book may help people with disabilities, their families, village workers, and rehabilitation professionals to learn more from each other, and to help each other to become more capable, more caring, human beings.

HOW THIS BOOK IS ORGANIZED

This book is divided into 3 parts: 1) “Working with the Child and Family,” 2) “Working with the Community,” and 3) “Working in the Shop.”

The disabilities that villagers usually consider most important are discussed in early chapters, beginning with Chapter 7. In many countries, many children with disabilities have paralysis or cerebral palsy. For this reason, we start with them. Other disabilities are arranged partly in order of their relative importance, and partly to place near to each other those disabilities that are similar, related, or easily confused.

Secondary disabilities are problems that result after the main disability. For example, contractures (joints that no longer straighten) can develop with many disabilities. In many villages, there will be more children who have contractures than who have any single primary disability. For this reason we include some of the important secondary disabilities in separate chapters.

Common disabilities that are often secondary to other disabilities include:

Contractures, Chapter 8

Dislocated Hips (either a primary or secondary disability), Chapter 18

Spinal Curve (either primary or secondary), Chapter 20

Pressure Sores (often occurs with spinal cord injury, spina bifida, or leprosy), Chapter 24

Urine and Bowel Management (with spinal cord injury and spina bifida), Chapter 25

Behavior Disturbances, Chapter 40

Other disabilities that are often the primary disability but commonly occur with other disability—usually with cerebral palsy—include seizures (Chapter 29), vision problems (Chapter 30), and hearing loss and speech problems (Chapter 31).