Hesperian Health Guides

Ear infection

HealthWiki > Helping Children Who Are Deaf > Chapter 15: Why children lose their hearing and what we can do > Ear infection

Ear infections are one of the most common childhood illnesses and without treatment, they can cause permanent hearing loss. Ear infections often start with an infection of the nose and throat. The infection travels from the throat along the tube into the middle ear.

Children get these infections easily because the tube from the throat to the ear is shorter than in adults. When the ear is infected, the fluid and infection cannot drain out of the middle ear. And if a child has a cold, the tube from the throat that leads to the middle ear often gets blocked. As children grow older and stronger, they develop more resistance and get fewer colds and throat infections.

Contents

Sudden ear infections (acute)

Sudden middle-ear infection can occur at any age, and is common even in babies and infants. The child may cry, be irritable, and have a fever. Often the infection gets better in 1 or 2 days without any treatment. A mild pain reliever such as acetominophen may help the child feel better but will not cure the infection. Sometimes an antibiotic is needed to cure the infection. The ear drum may burst and pus leaks out through a small hole. This hole usually heals quickly.

Long-lasting ear infections (chronic)

When children do not get treatment for repeated sudden ear infections, the infection can become long-lasting. An ear infection is long-lasting if pus drains from the ear and there is discharge for 14 days or more. This can damage the ear drum. The ear drum may become pulled inward or have a hole that does not heal. Both of these problems lead to more infection with discharge.

Without proper and early medical care, children may lose their hearing, or have dizziness, weakness on one side of the face, or an abscess draining behind or below the ear. Rarely, an ear infection may also cause a serious complication like a brain abscess or meningitis.

More poor children lose their hearing because of ear infections than any other cause. Hearing loss due to ear infections can be prevented by improving general health and living conditions, and by access to medical care. Every community needs people trained to identify ear infections early, or clinics or hospitals that are affordable and easy to get to.

Glue ear

Sometimes after sudden ear infections, thick and sticky fluid collects in the middle ear (this is called glue ear). Glue ear does not usually hurt and drains away down the tube to the nose after a few weeks, but sometimes it lasts for years. Glue ear often affects both ears and causes hearing loss as long as it lasts. Most cases of glue ear will heal without treatment. But if there is any pain, give an antibiotic by mouth as for acute infection.

Signs of ear infection:

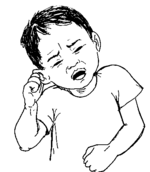

- Pain—a young child may cry, rub the side of his head, or pull on his ear.

- Fever between 37.7°C and 40°C (100°F and 104°F).

- Runny nose, sore throat, cough.

- Fluid may drain from the ear. It may be yellow, white, watery or sticky. The fluid may have some blood in it. A heavy flow of sticky, clear fluid is probably from a hole in the ear drum. This fluid may stop with medicines, but it can happen every time the child has a cold, or puts his ears under water or swims.

A slight fluid discharge that smells and may be yellow or green is probably from damage to the ear drum. An operation may be needed to repair the ear drum.

- Hearing loss—temporary or permanent—in one or both ears.

- Sometimes nausea and vomiting.

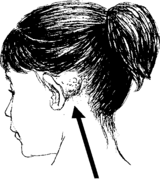

- Sometimes infection spreads to the bone behind the ear (mastoiditis). This is very painful and antibiotics must be given.

Go to a hospital!

Different signs may be present at different times—for example, the pain may stop when fluid starts flowing out of the ear.

Check the ear in 3 to 4 months after any ear infection, even if there is no pain and also check the child's hearing.

Treating ear infections

Note: When children need antibiotics, it is best to calculate the dose based on weight. See Where There Is No Doctor, page 340, for how to do this. If you cannot weigh the child, calculate the dose based on their age.

| To treat sudden (acute) ear infections | ||

|---|---|---|

| For pain and fever: | ||

| ||

| less than one year | 62 mg (⅛ of a 500 mg tablet), every 4 to 6 hours |  |

| 1 to 2 years | 125 mg (¼ of a 500 mg tablet), every 4 to 6 hours | |

| 3 to 7 years | 250 mg (½ of a 500 mg tablet), every 4 to 6 hours | |

| 8 to 12 years | 375 mg (¾ of a 500 mg tablet), every 4 to 6 hours | |

| or | ||

| ||

| 6 months to 2 years | 50 to 100 mg, every 6 to 8 hours | |

| 2 to 6 years | 100 to 150 mg, every 6 to 8 hours | |

| 6 to 12 years | 200 to 300 mg, every 6 to 8 hours | |

| Note: Do not give ibuprofen to children less than 6 months old or who weigh less than 6 kg. Give with milk or food to prevent stomach ache. | ||

| If paracetamol or ibuprofen alone does not lessen pain, using both together may help. For how to do this, see Helping Children Live with HIV. | ||

| For the infection: | ||

| ||

| less than 3 months | 125 mg, 2 times a day | |

| 3 months to 3 years | 250 mg, 2 times a day | |

| 4 to 7 years | 375 mg, 2 times a day | |

| 8 to 12 years | 500 mg, 2 times a day | |

| After 3 days, if the child’s ear pain and fever are not improving or if symptoms are worsening, stop giving amoxicillin and give the treatment below instead. | ||

| If ear pain and fever are not improving or symptoms are worsening after 3 days: | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| If the child is allergic to penicillin: | ||

|

| |

| or | ||

|

||

| 1 month to 1 year | 125 mg, 2 times a day | |

| 2 to 5 years | 250 mg, 2 times a day | |

| 5 to 12 years | 500 mg, 2 times a day | |

| Do not give more than 1 g (1000 mg) in 24 hours. | ||

| or | ||

| ||

| 1 to 2 months | 62.5 mg, 2 times a day | |

| 2 months to 1 year | 125 mg, 2 times a day | |

| 1 to 8 years | 250 mg, 2 times a day | |

| 8 to 12 years | 500 mg, 2 to 3 times a day | |

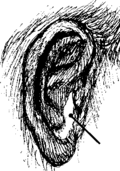

If there is fluid draining from the ear, wipe it away, but do not stick anything in the ear to clean it. Encourage the child to rest and drink a lot of liquids. The child can bathe, but should not put his ears under water or swim for at least 2 weeks after he is well.

If you think the child may have a complication, take him to a hospital. If you suspect meningitis, give medicine immediately.

| To treat long-lasting or repeated (chronic) ear infections (discharge for 2 weeks or more) | |

|---|---|

|

|

| If antibiotic ear drops are not available: | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

Repeat the same treatment if infection and discharge occurs again. A health worker or doctor can teach parents to clean out the discharge with cotton wool before each dose of ear drops.

Keep all water out of the ear. Carefully dry the ear two times daily with cotton wool or gauze for several weeks (until it remains dry).

When the ear drum bursts, sometimes an operation is needed to repair it. This is done by a specially-trained health worker in a hospital, usually when the child is at least 10 years old.

Preventing ear infections

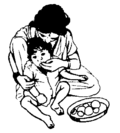

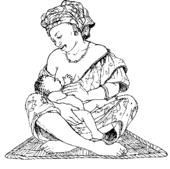

To prevent ear infections, breastfeed babies—for up to 2 years if possible. Breast milk helps a baby fight infection. Breastfeeding also helps strengthen the muscles that keep the tubes between the throat and middle ear open.

Other ways to prevent ear infections

- If a baby has to be fed from a bottle or a cup, keep his head higher than his stomach as you feed him. Otherwise the milk can flow from his throat into the tubes and into his middle ears, helping to cause infection.

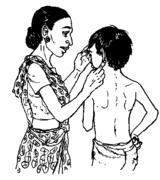

- Teach a child to wipe his nose instead of blowing it. If he does blow his nose, he should do it gently.

- When your child has a cold, find out if he also has ear pain. As much as possible, keep your child away from people with colds.

- As much as possible, keep children away from smoke, including smoke from stoves and cooking fires. Smoke can make the tube between the throat and middle ear swell and close. Then fluid builds up in the middle ear and it can get infected.

- Make sure children have enough nutritious food to eat. Malnourished children are more likely to develop infections, including ear infections. These last longer and are more likely to cause serious health problems than when children have enough to eat.