Hesperian Health Guides

Helping children when caregivers are very ill

HealthWiki > Helping Children Live with HIV > Chapter 6: Helping children through death and grief > Helping children when caregivers are very ill

Contents

Illness in the family

Rebecca, June, and Sarah are sisters. Rebecca is 12 years old, June is 7, and Sarah is 3. They live with their mother, Anabel, in a town in Tanzania. Anabel has HIV and is becoming more ill. Sarah also has HIV. Her father died when she was 2.

As the oldest child, Rebecca has left school to take care of her mother and sisters. She is afraid her mother might die, and worries about how she and her sisters will survive.

June believes that caring well for their mother will make her well. She helps by looking after Sarah, but sometimes wishes she could play instead. When Sarah is difficult, June tries to be patient, but sometimes she becomes upset and yells at the little girl.

Sarah is too young to understand her mother’s illness or why June and Rebecca are sometimes upset with her. She herself was small and weak until starting ART a few months ago, and she still often acts younger than her age.

Anabel worries for her children’s future. Her mother lives nearby, but is very old. Her brother William lives far away in a big city and was very upset when he learned that she had HIV. Anabel does not know if he is willing to help her children. It is hard to think about this, but she knows she must.

Miriam, a volunteer from a local church, comes to see them once a week. Sometimes she brings food, sometimes she helps in other ways.

Hello Rebecca, hello June. How are you today, girls?

Hello Miriam. Sarah wet her bed twice this week, and we don’t know what to do!

And she won’t take her medicine. |

That must be hard. I have rice for you. Tell me how your Mama is today. |

Loss and grief begin before death

When a parent, or child, is very ill — whether from HIV, cancer, or another illness — everyone in the family feels distress, including the children. Like Sarah, a child may respond by misbehaving, wetting the bed, not eating, not speaking, or acting younger than her age.

Children do not decide to do these things on purpose. They just have no other ways to show their distress. For more ways to help children who show distress with difficult behavior, see Communication improves behavior problems.

To help children facing loss:

|

June, you swept the yard well. I am proud of you. |

I have some fresh vegetables for you today, Rebecca. And some plastic for Sarah’s mat |

|

|

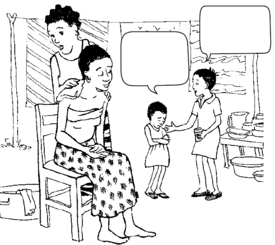

Sarah, your dolly seems happier than you do today. Can you tell me what is wrong? |

Ways to prepare a child for loss

Many families avoid talking with children about serious illness, thinking it protects them. But not talking with children may leave them afraid of what is happening, alone with their fears, and shocked by the death when it comes. Even a dying child may have these fears. Here are some ways to help children prepare to face a death in the family.

Tell children what is happening, in ways they can understand

Although it may be difficult, find ways to explain what is going on that the child can understand. Give a little information at a time, and make it easy for the child to ask questions. Let children know that any feelings they have are OK.

See Chapter 5: Talking with children about HIV, for ways to talk to children about illness and HIV. To talk with a child who worries he is dying, see How to support a dying child.

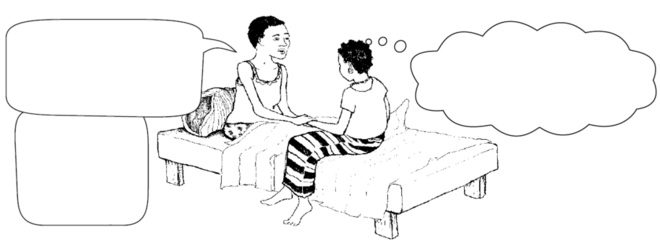

When a parent may die soon, prepare the child by talking about what will happen and where the child will live after the parent dies. If possible, it usually helps the child to be able to say goodbye and hear some last words.

Help children find ways to remember those they lose

When families share and write down their own stories, memories, and hopes for the children, it helps children feel connected to their parents later. Making a memory box together can also help families talk about illness with children and discuss plans for the future, if needed.

Sharing family memories helps most if it starts while the parent is still alive. However, even long after a parent’s death, sharing keepsakes or memories of a loved one can help children feel less alone, go through the grieving process, and strengthen their sense of who they are and where they come from.

How to make a memory box or book

Choose a safe container in which to store mementos, such as a bag, shoe box, or basket. Or make a book out of:

Put things in the book or box that hold meaning for your family — photos, events or dates, or memories about your children. Write family stories, history, or other things you want your children to know. If you cannot write, ask someone to write things for you. Include video or sound recordings if you can, and make copies for safekeeping. Encourage children to draw or tell stories about the times they want to remember and add them. Help children remember happy times. Let them decorate the box so they feel it is theirs.

Making a memory box can help families speak about fears and sadness too. Sharing these feelings and preparing for the difficulties to come can bring families closer together.

| Things you might put in a memory box |

drawings

messages for the child

a journal, diary or recipe book

family hand prints

a comb

photos

a family tree, with clan names

a list of

birthdays

a ring, watch or bracelet

buttons

seeds from the garden ...or anything that can remind the child of the parent. |

Help children feel less alone

When anyone feels alone with their problems, it makes them feel worse. You can help a child feel less alone when facing a loss.

- Read or tell stories about other children who have lost parents or other loved ones. Hearing about what happens to other children, how they feel, and how they are able to go on with their lives, can help a child greatly.

- Help children keep up their activities with friends. A child’s grief will come and go, and doing the usual things with friends makes grief and changes at home easier to bear.

- Encourage relationships with other caring adults, especially those who will care for the child after the parent dies.

Planning for the future

When someone is seriously ill, it may be difficult to think about things such as legal documents, funeral arrangements, or where children will live. But planning for the future makes it much easier for children later. And knowing things are taken care of may give some peace to the person who is ill.

| Helping Anabel make plans| |

| Anabel says to Miriam one day, “Where will the children live when I am gone? I wish they could stay here.” Miriam asks, “What family do you have nearby?” “My mother,” says Anabel, “but she is old and barely gets on. My brother William might take them, but he lives so far away, and the girls would lose the house and land.” Miriam asks, “Would your brother help the girls stay here?” Anabel says, “Mmm, I will discuss this with him.”

You are very responsible, Rebecca. When I am gone, I know you will take care of your sisters.

How can we bear to lose Mama and our home too? We do not even know Uncle William.

Your Uncle William wants to help. He says you can live with his family in the city. Rebecca hates to think of her mother dying and the changes that will bring. Anabel says, “The city has good opportunities!” But Rebecca says, “We all like it here! Why must we move?” Rebecca knows June and Sarah will not want to leave either.

You need to go to school, Rebecca — you cannot take care of the girls alone. William would be a good father.

What about June? She is already so upset. Why can’t we stay here, in our own house?

I do not like to leave the girls here on their own. But perhaps if Mama Patrice came to live with them.

Would you be willing to take the girls later if needed?

And perhaps help with school fees?

I’m so sorry babies.

Mama, no! When William leaves, Miriam asks “Have you made a will yet, Anabel?” She has not, but realizes her girls will be more secure if she does. Miriam helps her write her wishes, and Miriam and a friend witness it.

|

Where should children live?

Traditionally, orphaned children are taken in by whichever family member is most willing and able to support the child. This makes sense and often works very well for the children.

Families facing this decision often think mainly of who has the resources to support another child. But it is also important to think of where the child will be most accepted, understood, and loved. A less well-off but loving caregiver may take better care of the child than someone who is resentful of the obligation, did not approve of the child’s parent, or will not protect the child from abuse or rape. Who will best help the child with her grief? Who will help her keep the good memories of her family alive?

Keep siblings together whenever possible. Losing a parent is hard enough, but losing the entire family to separation makes the loss much worse. If children cannot be in the same household, try to keep them near each other in the same community. Having a sibling close by helps each child cope better. Children do better when they continue to live with or near caring people they already know and trust.

When possible, involve children in decisions. Children may have opinions about where they should live, and their ideas should be listened to and considered. By taking children’s feelings and ideas into account, you can lessen their feelings of powerlessness. Give them as much information as possible and be honest. If you talk to them about their future and prepare them for what will happen, it will not make their worries go away, but it will lessen them.

Making this effort is important because sometimes children are treated badly by a new family or at an orphanage. Children may be forced to eat separately or be given less food than others. They may be treated more like servants than members of the family, or be made to feel unwelcome, unworthy, or like a burden. HIV stigma is often part of this.

Communities can support families more by helping them apply for aid they are entitled to, by recognizing and praising families that adopt children, and by teaching everyone about HIV so people have less fear and predjudice. Communities also have a role in preventing child abuse. See Chapter 14 for information.

Support the family to prepare for coming needs

- Help them start saving or find community support to pay for the funeral.

- Ensure that children are registered or have identity documents.

- Gather any land titles, other property ownership documents, and insurance policies. Make sure these and other important papers and family things are stored safely. Children should know where they are, and an older child should be able to access them.

- Make wills or guardianship legal and known to respected authorities in the community and the extended family on both sides. It may be emotionally difficult to do this while parents are healthy. But it will be more difficult to do when illness is severe and death is near.