Hesperian Health Guides

Helping children after a caregiver dies

HealthWiki > Helping Children Live with HIV > Chapter 6: Helping children through death and grief > Helping children after a caregiver dies

Community spiritual and religious beliefs and customs related to death and burial can help children when there is a death in the family. Talking about your spiritual beliefs may comfort a child. Rituals bring people together for comfort, and help everyone understand what death and loss mean. Even when certain parts of a funeral or ritual do not make sense to a child, he will usually find comfort in watching how people mourn together and remember the person who died.

While no child should be forced to attend rituals and ceremonies, participating in some way usually helps a child deal better with death. If possible, discuss with the child what his customary role would be, and ask if there is another way he would like to participate, such as putting flowers on the grave, or making a note or picture to bury with the person or put on an altar. This can also help a child understand the death more.

If attending the funeral is not possible for the child, it can be helpful to arrange another way for the child to say goodbye. Have a separate memorial at home with music, drawings, and short speeches, or light a candle together while you talk about the person. Or you might invite people close to the child to join him in looking at things in a memory box and adding things to it.

Contents

Protect children’s resources

Often when parents die leaving behind very young children, their land and belongings are taken by other relatives or distributed according to tradition or a local leader’s decision. Talking with the family, local authorities, or a court can help protect the children’s rights.

Help children with grief

How children understand death and show grief changes with their age, and even children who are the same age show grief in different ways.

A child may act very upset, or may seem to feel nothing. She may ask a lot of questions, freely say how she feels, or she may say little. She may be shy, or play roughly, or have trouble sleeping or behaving well. She may even seem unwell, with headaches, belly aches, or other pains. While it is important to pay attention to these problems, what is more important is that you respond with extra attention and love, as much as you are able.

Grief and the changes that come with loss are very difficult for anyone, but especially children. Anger and misbehaving are common signs of grief. If you start by understanding that children act as they do because of grief, it will be easier to be patient and find ways to help them. With time and support, children will be able to grieve, grow and develop their skills and talents, learn self-confidence, and see that life goes on.

When a child is grieving:

|

I miss my friend who died so much, and it makes me sad. But I will be OK soon. |

|

Yes, you can play. I am here if you need me. |

|

|

|

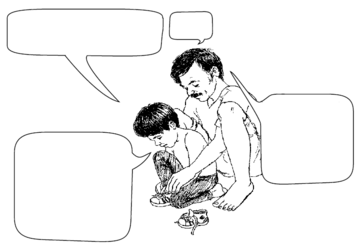

No Simon, I don’t think you’re bad — I think you’re just angry. Let’s go chop some wood. |

| |

|

|

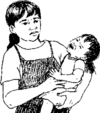

A child from birth to 2 years old

A child under 2 years old is deeply attached to his mother. He knows her face, voice, and smell, and is used to being held, fed, and loved by her. He feels safe when she is near. Losing a mother can be very hard on children this age, and they are too young to understand death. But babies can be strong and adaptable if a new, loving person cares for them.

|

|

|

Signs of distress:

- Distressed babies may cry more, be more difficult to comfort, or have more tantrums.

- The babies may become aggressive, hitting or throwing things.

- The babies may seem fearful, clinging more to caregivers, or withdrawing.

- You may notice changes in eating and sleeping, and in passing urine and stools.

- The babies may not make the progress you expect in learning to crawl, sit, talk, and walk.

How to support the child:

- Arrange to have one main caregiver, rather than several different ones, to help her feel secure.

- Cuddle, rock, and walk babies when they are upset. You can also comfort a baby with blankets and soft toys they are used to. Some babies like to be wrapped firmly in a light blanket or cloth. Being held is most helpful.

- Sing and talk to the baby, and repeat the baby’s sounds to him. Encourage older sisters and brothers to do the same.

- Try to feed the baby, and put her to sleep, at the same times each day.

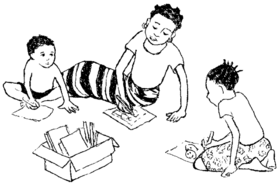

A child from 2 to 3 years old

A child this age does not understand that the person who died is gone and cannot come back. He may feel abandoned or rejected when a parent dies. Children this age are often difficult to calm. They feel everything strongly, but cannot understand why they feel the way they do. They often show grief and sadness in physical ways.

Children this age are best cared for by someone they were comfortable with and knew before the loss of their parents. Being with siblings and in a familiar place also helps.

Signs of distress:

|

| |

|

Wet again! |

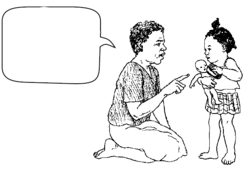

Where is Mama? I want Mama!

I’m sorry Kiki. Your mama has died. I know you miss her! |

|

||

|

|

|

How to support the child:

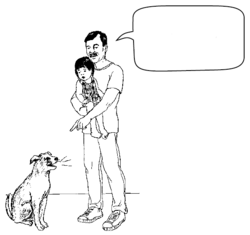

|

Don’t worry, Joy, he is a friendly dog. |

|

What is the dolly drinking, Kisha? |

|

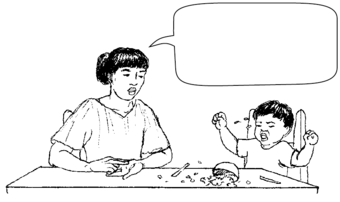

I see how angry you are that Papa’s gone. When you calm down I will help you eat. |

|

Did you pat the soil down? Good! |

Routines still help children this age. Try to wash or feed your child or have him nap at the same times each day.

A child from 3 to 6 years old

Children this age are able to communicate more, and want to talk with you about their thoughts and feelings. They also want to know more about what is happening in the family. Listen to them carefully to understand what they want to know, and answer simply and honestly, in ways they can understand. A little information may be all they want. They also still work out many feelings through actions and play.

Most children this age can understand how birth, life, and death are a pattern all around us and that all living things follow this pattern — plants, animals, and people.

Children this age have strong imaginations. They play games of sickness, doctor, and death, which can help them come to terms with difficulties.

They also believe in things that are not real, such as ghosts and monsters. These beliefs can make their fears very strong. Children this age also believe their thoughts and actions can make bad things happen.

Signs of distress:

- Sadness and crying. Longing for the parent and asking where she is, or about the death. A child who asks over and over again about a parent’s death may be worried you will die too.

- Running away from a new home to try to go back to the one they know.

- Fears — of the dark, of sounds, or of being alone.

- Acting younger than their age, for example, clinging to a caregiver or being less able to talk or understand simple directions.

- Bursts of anger at caregivers and playmates.

How to support the child:

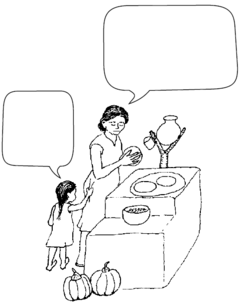

|

You miss your Mama’s cooking, don’t you? Let’s cook something together.

Stew? |

|

|

|

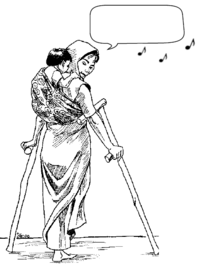

Listen! Remember how Mama loved this song? |

|

I was so mad at Papa I wished he was dead! Then he died.

Oh no, Peter! Your Papa died because he was very ill. You did not make that happen! |

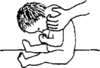

A child from 6 to 8 years old

Children this age can talk and think about complicated subjects. They may want to know more about why people become ill or die, and what happens after death. They may also wonder about their own health, and what it means if they take medicines or are HIV-positive.

They feel grief deeply and will continue to need lots of affection and help. Like younger children, they may worry they caused the parent’s death and need reassurance they did not.

Feelings may change quickly — sadness may become mockery at themselves or at others. Children this age are more able to talk about their feelings. Even so, it often helps when they can use toys, drawings, or play to let out and deal with their feelings.

Signs of distress:

- A distressed child may be sad, and long for the person who died.

- The child may be angry at caregivers or friends, play roughly with toys, show poor behavior at school, or be less willing to take medicine.

- The child may be afraid that he or his new caregivers will also die, and be reluctant to start new relationships.

- The child may not want to be alone, especially at night.

How to support the child:

- Explain family and community rituals, and support children’s participation as much as possible.

- Remember the person who died. Talk with the child about the person and look at photos or at things in a memory box. Children this age may be able to imagine the person with them in spirit.

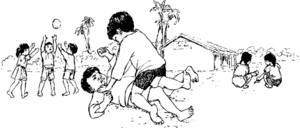

- Encourage children to play and be active when they are sad. Introduce them to new friends.

- Decide with the children what to do with the parent’s belongings.

- Be understanding if the child is clingy. Tell him where you will be when you part, and when you will be together again.

- Be honest with the child. Never make empty promises, especially if they ask you for something.

- If children are destructive or mean because of anger or frustration, try to support them in a loving way. Ask them to take responsibility for any harm they cause.

How school can help

School can be a place of stability and routine for children who have lost a parent, and a way to forget sadness at home. When teachers and students acknowledge a grieving child’s learning and new skills, it builds her confidence, self-esteem and hope. Heavy workloads on teachers can make it difficult to provide this support however, and many teachers are not comfortable talking to children about death. Teachers may not know that a child’s difficult behavior could be a sign of grief.

In communities with a lot of HIV, training teachers to better understand and support grieving children can help many children in need. In addition, someone may be willing to organize a support group at a school, where children who have lost a parent can share experiences and support each other. Schoolmates can be important friends. But sometimes when children’s parents die, those children are teased or rejected by other children. Teachers, families, and students need to work together to make this unacceptable and show that all children are worthy of acceptance, compassion, respect, and friendship.

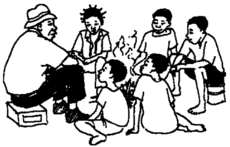

Storytelling

Storytelling can help children of almost all ages to understand, think, and talk about illness, death, and grief. Telling a story can be a way to explore a child’s troubles without using real names or real people. You can also use animals in place of people. See the story that follows.

Stories can help children with grief

After Anabel dies, Rebecca carries on as head of the family, with help from their grandmother. Rebecca feels they are doing OK, but June is taking her mother’s death hard. During all the months of illness, June thought her mother would get well. Now June is very upset and does not want to eat. And she has even less patience with Sarah. One day June’s grandmother decides to tell June a story, to help them talk together about how she feels.

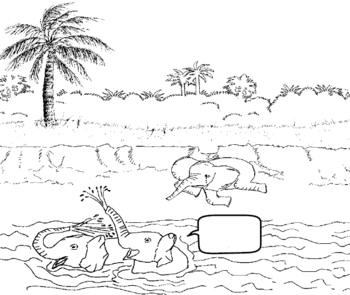

Sylvia loved to bathe and play in the river with her friends. But most of all, she loved eating tree bark! It was her favorite!

Most of the time Sylvia was a very happy little elephant. But one day she saw her mother taking medicine. Then she saw that her mother went to see the medicine elephant more than any other elephant in their herd.

Then her mother got very ill, and soon she could no longer walk and eat with the rest of the herd.

A little later her mother died.

This made Sylvia very sad and also very angry. She stopped playing in the river and refused to eat, even tree bark!

Sylvia’s papa said, “Baby, you must eat!” But she refused.

Sylvia’s friends called, “Come play!” But she refused.

Finally Sylvia’s wise old grandmother elephant asked, “My dear, what is troubling you? I see that you are not eating your favorite foods and not playing with your friends. Come tell me about it.”

After walking a while with her grandmother, Sylvia finally said, “I miss my mother. I hate that she is gone! When I think about her I don’t want to eat anything, not even tree bark!”

Grandma elephant took Sylvia in her trunk. She rocked her back and forth and said that she knew how it felt to be sad.

She talked about how sad she was herself when Sylvia’s mother died. Grandmother elephant had loved her too. They both cried a little.

But Grandma elephant knew that the whole family must still eat and care for each other and continue to live. She asked Sylvia what she liked to remember most about her mother. “Everything!” said Sylvia. Grandma elephant remembered how Mama elephant played splashing games in the river with Sylvia, and this made them both smile.

After talking for awhile, Sylvia and her grandma began to feel better. They walked back to the herd. That night Papa elephant gave Sylvia tree bark for dinner. And she ate it all up!

Sylvia still feels sad and misses her mother, but she thinks about what Grandma said and that usually makes her feel a little better.

Even if you provide lots of love and support to a child, he may still struggle a lot after someone’s death. It is common for a child (or anyone) to keep feeling very sad and even angry for a long time. Holidays can be worse as can any time something reminds them of the person who died. Many months later, children may misbehave or feel the same strong sadness they felt right after the death. This is to be expected.

But if a child continues to have a lot of trouble more than a year after the death of a close family member, you may want to get more help. This could come from a clinic, a social worker, a community organization, an HIV support group, or a religious congregation. Get support from your community. You and the child do not need to struggle alone.