Hesperian Health Guides

Make judicial systems work to stop violence

HealthWiki > Health Actions for Women > Chapter 6: Ending Gender-based Violence > Make judicial systems work to stop violence

Contents

Learn about legal protections

The laws, courts, police, and other authorities each play an essential role in controlling violence in a community. But information about how each part of the justice system deals with gender-based violence is often confusing. To more effectively fight gender-based violence, people need to learn about the legal protections that exist, and the gaps between how laws are written and how they are applied. Then we can work on getting better laws, and better enforcement, and changing attitudes.

A group can use the next activity to learn about the roles and duties of authorities to support victims of gender-based violence.

Activity

Group investigation about roles and duties of local authorities

Prepare ahead of time by learning as much as possible about the law. If possible, find someone with knowledge about the judicial system to support you and participate as a resource person. This process will work best if you can identify people from different local authorities who are open to talking with your group.

-

Who can you turn to? To begin this process, bring the group together and ask the group to discuss this question: "Who can you go to for help if there is an incidence of violence against women in your community?"

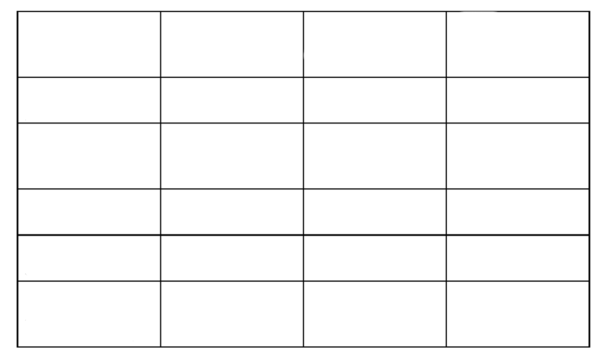

Make a grid like the one below on a large piece of paper that everyone can see. In the first column, write the different authorities that the group identified. Ask the resource person to add any that the group may have missed.

-

Explain that the purpose of the group investigation is to learn how each of the authorities acts to end gender-based violence by answering these questions:

- What does each authority do now to address violence against women and LGBT people?

- What do they not do? What are they not able to do? Why?

- What other things should they be doing to address this type of violence?

- Investigate! It may take several weeks for each team to collect the information they need through interviews and other research. For example, they may try to interview several people inside each institution to gain different points of view. They may also be able to interview women who have gone to different authorities for protection or seeking justice. Recent news stories and court records can help explain what authorities do and do not do.

- Once the groups have completed their investigations, convene a meeting for the teams to report back to the whole group. Be sure to allow for plenty of time for each team to present and for everyone to ask questions.

- To conclude, ask the group to reflect on what they have learned from this process, and what might be the focus for next steps towards making the justice system work better. For example, the group might want to focus on making more people aware of local authorities’ duty to respond to cases of violence against women. Or they might want to try to make it easier for LGBT people to report the crime to police. To develop a plan, it may be helpful to follow this discussion with the Make a power map activity.

Work with local courts and police

Judicial systems can become more supportive of women when judges, lawyers, court authorities, and police officers recognize that women and LGBT people are not treated fairly and that the authorities must act to defend and protect all people’s rights. Involving those authorities in efforts to improve the system often requires time, a variety of strategies, and many meetings. You may need to work with community leaders to find people in the judicial system who are most likely to listen and to support your proposals. You may also find that some authorities will not change and you must advocate for their removal.

Here are a few examples of ways that you can improve judicial systems:

Female police units. Women often feel uncomfortable or unwilling to speak with a male police officer to report rape or domestic violence. In the 1980s, women’s organizations in Brazil advocated for police units staffed entirely by women. The first all-female units were created in 1985, and many countries now use this model. Social workers often work alongside police to help women understand their rights, make decisions, and get health care and other services.

Police trained in gender-based violence. Community activists can also provide ongoing training on gender-based violence. Some police officers do not enforce laws against domestic violence or gay bashing. They may refuse to admit that violence happens, and they themselves might abuse women or threaten gay people. To change long-held attitudes and prejudices, police officers need opportunities to learn new perspectives.

Domestic violence courts. Women are often afraid to report an abusive partner to authorities, because they depend on the partner for food and shelter. If her partner is sent to jail, a woman may lose her home or other resources. If he is not sent to jail, he may hurt her even more. Women trapped in situations of domestic violence often report abuse but are unable to break free and leave abusive partners. This can lead to repeated court cases that do not end the abuse. In the United States, several local court systems have responded to this pattern by creating problem-solving domestic violence courts.

The problem-solving courts provide social services, such as housing aid and job training, as soon as a woman’s case is filed with the court. Women also receive training in planning for safety and creating escape plans for violent situations. (See Support survivors to escape domestic violence.) These courts also help keep women safe during and after the court proceedings by monitoring the behavior of their abusers. This approach speeds up court proceedings and enables survivors to leave the court system and their abusive relationships for good.

Restorative justice. When a community group helps survivors of domestic violence or gay bashing to confront and negotiate with their abusers, this is called restorative justice. Creating the conditions for this kind of community accountability takes time and training. It works best when there is strong community support.

Criminologist

Independent court systems. In four different cities in India, a group named Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan (BMMA) set up its own courts for women’s legal issues. In the past, divorce and child custody cases were either handled by the state system or resolved through the Sharia (Islamic law) courts run entirely by men. These courts rarely ruled in favor of women, who were often left without financial support for themselves and their children. BMMA is working to create national laws that strengthen existing protections for women under Islamic law, and also to provide legal support to women who decide to use the state court system.

Human rights laws can help

Under international human rights law, sexual violence committed as part of an attack against a civilian population is considered a crime against humanity. This means that the harm done to one group is an injustice to all people. Many groups use human rights laws when they demand justice from local courts and governments. (For more information, see Appendix A: Advocate for Women’s Rights Using International Law.)

Organize to bring justice for survivors

No matter how much you do to educate the police, set up alternative courts, and design systems for restorative justice, you will still need to mobilize support in the community. If you can organize the community to understand and take action on the problem of gender-based violence, you will have forged a powerful tool for bringing justice to survivors. With a strong grassroots base, you can, for example, mount campaigns against judges who consistently discriminate against women and LGBT people, forcing those judges to change or step down. You could also organize your community to pressure the health center to develop better protocols for documenting abuse.

|

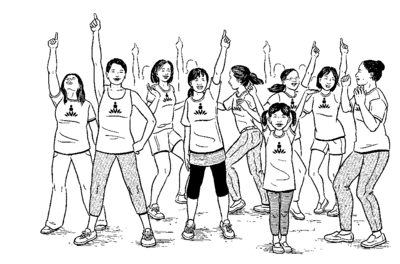

On February 14, 2013, women in Hong Kong joined with one billion people in 207 countries to rise and dance to demand an end to violence against women and girls. For more information about "One Billion Rising for Justice," go to: www.onebillionrising.org |

By connecting with global movements against violence, you can strengthen your organizing and get more media attention. V-Day, a global activist effort to end violence against women and girls, raises awareness and money and helps energize organizations fighting violence. The International Day Against Homophobia is another opportunity to join a large-scale, media-attracting event. Celebrated on May 17 — the anniversary of the day in 1990 that the World Health Organization removed homosexuality from their list of mental illnesses — this event helps people raise awareness of LGBT issues in their communities, workplaces, and families.

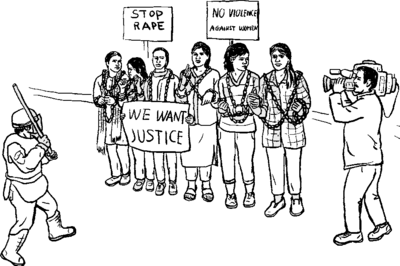

Protests in India demand an end to violence against women

In December 2012, a 23-year-old woman was attacked and raped by 6 men on a bus in New Delhi, India. A male friend who tried to defend her was badly beaten before he and the woman were both thrown from the bus. Strangers found them by the roadside and took them to a hospital. The woman died 2 weeks later from her injuries. News of the attack spread quickly around the city and the country. A few days later, thousands of demonstrators gathered in Delhi and other cities to protest the government’s slow response to the brutal rape and to demand an end to the widespread problem of sexual violence in India.

Women’s groups and other organizations in India have spoken out for years against rape and all forms of violence against women. But the massive protests — and police repression of them — attracted the news media’s attention to these problems as never before. Many protestors reported personal and family experiences of sexual harassment and rape. They were already angry at the police and the courts for dismissing their complaints and failing to punish attackers, but they had never felt they could speak out or demand justice.

Both men and women joined the protests to denounce common attitudes toward women rooted in the idea that women are men’s property to use as they wish. The protesters made it clear that women are not to blame for harassment and violence against them. One men’s group in Delhi showed solidarity with women by wearing women’s clothing for a day to call attention to the way that women are treated in public.

People around the world heard the protestors’ message. They demanded speedy arrests and trials for rape and sexual assault cases, stronger laws and enforcement for gender-based crimes, and safe public transportation for women.

International attention combined with local action created pressure for change. Several state governments strengthened rape laws and promised new services. The central government appointed a high-level committee to recommend changes to the law. Women’s groups were hopeful when most of their recommendations to the committee were included in the final report. But they were soon discouraged when the government passed an ordinance that ignored the report and failed to condemn all forms of gender-based violence. The ordinance was meant to calm protests, but instead it inspired new rounds of marches and rallies.

People in India continue to speak out about gender-based violence. The national and international media now report on more cases of rape and harassment. Organized groups continue to pressure the government to strengthen anti-rape laws and increase their enforcement. These actions replace a culture of silence about gender-based violence with a culture of voices demanding change.

Bringing attention to gender-based violence can be difficult, especially in places where it has been tolerated longer than anyone can remember. But when thousands of people take to the streets to denounce rape and sexual violence, it becomes an issue for the whole world, thanks to television, the Internet, and communication by mobile phone. Even when news reports are incomplete or one-sided, they can raise awareness and create an opportunity to discuss and debate how gender-based violence is addressed locally or nationally.