Hesperian Health Guides

Community solutions to make birth safer

HealthWiki > Health Actions for Women > Chapter 8: Healthy Pregnancies and Safe Births > Community solutions to make birth safer

Form an emergency health committee. A committee can be made up of midwives, nurses, doctors, husbands, pregnant women, teachers, and business owners who meet regularly to make sure services are available and adequate for pregnant women in the community.

|

Organize emergency transportation. Neighbors or business owners who own cars, trucks, or other vehicles take turns being available to take women to the hospital. Some communities have built bike trailers to carry pregnant women who need to go to the hospital. |

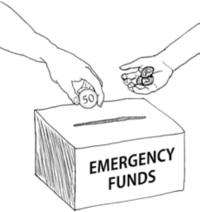

| Create an emergency loan fund. Each family contributes a small amount of money, so funds are always available to loan in an emergency. The emergency health committee decides how the money is used: to pay for medical care, fuel, transportation, or other things. The committee also decides when and how the money must be paid back to the fund. |  |

|

Safe motherhood houses. If a community is too far away from the hospital, or the road is bad sometimes, women will be safer during the last weeks of pregnancy if they have a place to stay closer to the hospital. If several communities can work together and get the support of the government health system, they may be able to pay for a small house or rent a room near a hospital in the city. Then pregnant women can go to the hospital quickly if there is an emergency. |

| Safe blood donations. One tribal leader in India had a relative who died when she could not get blood. The nearest hospital did not have a reliable blood supply. So this man encouraged community leaders in neighboring villages to donate blood and to organize yearly donation campaigns. The leaders asked local youth to lead these efforts. Now many people give blood. All the blood is screened for infections, so everyone knows it is safe. By doing this, these communities are helping save the lives of women who have heavy bleeding during childbirth. And because of this grassroots work, for the last 15 years, the hospital has always had a blood supply ready for any emergency. |  |

|

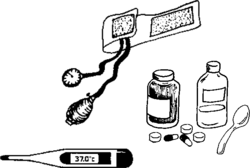

Community medicine kits. If anyone in the community knows how to treat some birth emergencies, then the community should buy some basic medical supplies and keep them in a safe place. Some examples of useful medical supplies are a thermometer, a blood pressure cuff, antibiotics to treat infection, medicine for seizures, and medicines for heavy bleeding after the birth, such as oxytocin and misoprostol. See A Book for Midwives or Where Women Have No Doctor for information about using these medicines. |

A man speaks out for access to emergency transport in Tanzania

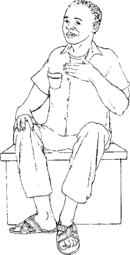

In a Tanzanian village, a 14-year-old girl named Teresia was pregnant. Teresia was not yet a fully-grown woman, and she had not planned on becoming a mother so young. The health center nurses knew giving birth could be dangerous for her and her baby because her pelvis was probably too narrow for the baby to fit through. They told her family she should give birth at the regional hospital in case she needed an operation. So her family saved money to pay for an ambulance. But when she went into labor, the price of gasoline had gone up, and the family did not have enough money to pay for the trip. The health center’s officer refused to let her ride in the ambulance, even though he knew her life was in danger. He scolded the family for waiting to go to the hospital, and said, "It is your responsibility if she dies." The village secretary, Abdallah Sadiki Aziz, heard of the problem and sold his bicycle to help buy enough gasoline for the ambulance, and he went with the girl and her family to the hospital. When they reached the hospital, Teresia had a Cesarean section, but her baby had died. Teresia never recovered from the birth and died a few weeks later.

Many months later, members of an organization called Women’s Dignity visited the village and talked with the local officers about safe motherhood. Abdallah spoke out, criticizing the local health officer for continuing to charge people who needed the ambulance service. Women’s Dignity invited him to a meeting with the district authorities where he explained how the officer had refused to help Teresia. Because of this, the officer in charge of the health center was transferred. Abdallah said, "The new clinical officer made sure that the ambulance is free of cost for pregnant women and small children with emergencies. The villagers are happy, and many have come to thank me for speaking out."

Abdallah was also invited to speak at Tanzania’s first Popular Tribunal on Girls’ and Women’s Lives. He was interviewed by reporters and spoke on national radio. People across the country learned what he had done, and about the dangers girls and women face every day giving birth. Abdallah says, "I don’t want to draw too much attention to myself, but I was glad I got a chance to tell district officials about Teresia’s case. I enjoyed speaking at the Tribunal, because I learned a lot about human rights, things I didn’t know before. I will use this knowledge to tell others in the village. But I don’t want people to think I am a troublemaker, especially not the health center staff. My wife, my children, and I rely on them when we are ill. However, if a similar problem happens once more, I would certainly speak out again, for the sake of the women of our village."

Change happens when people organize

Since Abdallah testified, there has been a wider push to promote safe motherhood nationally. Tanzania’s current policy, the National Road Map Strategic Plan, requires half of all health centers to provide comprehensive emergency birth and newborn services by 2015. Although these legal developments are promising, practices are slow to change. Safe motherhood advocates in Tanzania say women still pay bribes to get medical attention at health facilities and face constant shortages of basic birthing supplies and medicines. The laws are a step in the right direction, but now activists must continue to apply political pressure to uphold the new regulations.