Hesperian Health Guides

Types of Seizures

Note: This information is for rehabilitation workers and parents because many doctors and health workers do not treat seizures correctly. With care, perhaps you can do better. However, correct diagnosis and treatment can be very difficult. If possible, get advice from a well-informed medical worker. Ask her help in using this chart. It is adapted from Current Pediatric Diagnosis and Treatment by Hay Jr., Levin, Abzug, and Bunik (Lange Medical Publishing), in which more complete information is provided.

| TYPE | AGE SEIZURES BEGIN | APPEARANCE | TREATMENT | ||

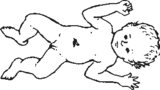

Newborn seizures (neonatal seizures) |

birth to 2 weeks | Often not typical of later seizures. May show sudden limpness or stiffness; brief periods of not breathing and turning blue; unusual cry; or eyes roll back; blinking or eye-jerking; sucking or chewing movements; jerks or strange movement of part or all of body. WARNING!: Make sure spasms are not from tetanus or meningitis. With cerebral palsy in the newborn, the baby is usually limp. Stiffness and/or uncontrolled movements usually appear months later, but the baby does not lose consciousness. |

Phenobarbital or phenytoin. Add diazepam if not controlled. (Seizures due to brain injuries at birth are often very hard to control.) |

||

|

|||||

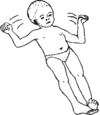

Baby spasms (infantile spasms, West’s syndrome) |

3 to 18 months (usually about 6 months) |

|

Sudden opening of arms and legs and then bending them, or repeat patterns of movement. Spasms often repeated in groups when waking or falling to sleep, or when very tired, sick, or upset. | Corticosteroids may be tried—but can be dangerous. Try to get help from an experienced doctor or health worker. Valproate or diazepam may help. | |

| Most children with these spasms develop cognitive delay. | |||||

| Fever seizures (Febrile seizures) | 3 months to 6 years (peak at 6 to 18 months) | Usually generalized seizures (see below) that happen only when child has a fever from another cause (sore throat, ear infection, bad cold, among others). Usually lasts less than 5 minutes but rarely can last up to 15 minutes. Often a history of fever seizures in the family. WARNING: Look for signs of meningitis. |

A child who has had fever seizures on several occasions should be treated for the cause of the fever. Lowering fever with paracetamol (acetaminophen) can prevent fever seizures from continuing. If the seizure lasts more than 5 minutes, use diazepam. Phenobarbital is rarely needed. | ||

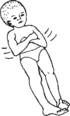

| Myoclonic seizures — sudden muscle jerks (Lennox-Gastaut syndrome) | any age but usually 2-7 years | Sudden violent spasms of some muscles, without warning, may throw child to one side, forward, or backward (drop attacks). Usually no loss of consciousness, or only brief. Many children also have generalized seizures. May be a history of baby spasms (see above) in earlier childhood. |

Difficult to treat. Try phenobarbital, with valproate. If no improvement, consider trying corticosteroids as in baby spasms, or other medicines with medical advice. Protect child’s head with headgear and chin padding. | ||

|

| ||||

| Blank spells or absences (childhood absence epilepsy) | 3-12 years |

Child suddenly stops what she is doing and briefly has an empty or blank look. She usually does not fall, but does not seem to see or hear during the seizure. These absences usually happen in groups and usually last 3 to 10 seconds. She may make unconscious movements, or her eyes may move rapidly or blink. These seizures can be brought on by breathing rapidly and deeply. (Use this as a test.) Often confused with psychomotor seizures, which are much more common. Unlike other seizures, the child may not experience a warning sign or aura, or confusion after the seizure. | Valproate or ethosuximide. Since many children also have ‘big’ seizures, add phenobarbital if necessary (or try it first if you think the seizures might be ‘psychomotor’ —see below). | ||

| Focal seizures (partial seizures) | any age | Movement begins in one part of the body. May spread and become generalized. Note: If seizures that occur in one part of the body get worse and worse, or other signs of brain injury begin to appear, the cause might be a brain tumor. |

Try carbamazepine. If seizures not controlled, try phenobarbital or phenytoin (or both). | |

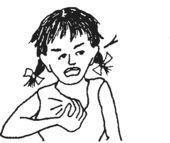

Mind-and-body seizures (psychomotor seizures) |

any age | Starts with warning signs: sense of fear, stomach trouble, odd smell or taste, hears or sees imaginary things. Seizure may consist of an empty stare, unusual movements of face, tongue or mouth, unusual sounds, or unusual movements such as picking at clothes. Unlike blank spells, these seizures usually do not occur in groups and they last longer. Most children with psychomotor seizures later develop generalized seizures. | Try phenobarbital first —then phenytoin, or both together, then carbamazepine, or both together, then carbamazepine, or all 3 together. Valproate may also be useful. Psychological counseling sometimes also helps. | |

ARHHH | ||||

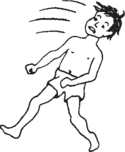

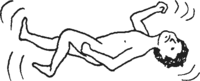

| Generalized or tonic-clonic seizures (also called big or grand mal) | any age | Loss of consciousness, often after a vague warning feeling or cry. Uncontrolled twisting or violent movements. Eyes roll back. May have tongue biting, or loss of urine and bowel control. Followed by confusion and sleep. Often mixed with other types of seizures. Often family history of seizures. | Try phenobarbital, carbamazepine, valproate. Combinations may be necessary. Phenytoin may be effective. | |

| ||||

| Temper tantrum fits (not epilepsy) | under 7 years | Some children in “fits of anger” stop breathing and turn blue. Lack of air may cause loss of consciousness briefly and even convulsions (body spasms, eyes rolling back). These brief episodes are not dangerous | No medical treatment is needed. Use methods to help the child improve behavior (see Chapter 40). | |

|

||||