Hesperian Health Guides

Chapter 34: Child Development and Developmental Delay

makes doing and exploring things more difficult

In Chapter 32 we discussed some of the primary causes of mental slowness. Mostly we looked at disabilities that come from inside a child’s head— conditions where the brain has been injured, is too small, or for other reasons is not able to work as quickly as other children’s brains.

In this chapter we see how a child’s early development also depends on factors outside the child’s head—on the opportunities a child has to use his senses, mind, and body to learn about the things and people around him. We look at the stages or steps of typical child development, and at ways we can help or stimulate a child to learn and do things more quickly. Our concern is not only to help children who have cognitive delay, but those whose development is delayed for whatever reason.

Usually children whose minds take longer to develop also take longer in learning to use their bodies. They begin later than other children to lift their heads, roll, sit, use their hands, stand, walk, and do other things. They are physically delayed because of their delayed mental development.

In other children the opposite is true: certain physical disabilities make more challenging for them to develop the use of their minds.

For example, a child who is born with hearing loss and does not have cognitive delay will have difficulty understanding what people say, and in learning to speak. As a result, she is often left out of exchange of ideas and information. Because language is so important for the full development of the mind, in some ways she may seem delayed for her age. However, if the child is taught to communicate her wishes and thoughts through sign language at the age when other children learn to speak, the development of her mind will often not be delayed Chapter 31).

Enrique's Story

Enrique had a difficult birth. He was born blue and limp. He did not start breathing for about 3 minutes. As a result, he developed severe cerebral palsy. His body became stiff and made strange movements that he could not control. His head often twisted to one side and he had trouble swallowing.

Enrique’s mother loved him and cared for him as best she could. But as the years went by, he did not gain any control of his body. His mother kept him on the floor in a corner so that he would not hurt himself. He spent most of his young life lying on his back, legs stiffly crossed like scissors, head pressed back, looking up at the roof and the mud brick walls. By age 3 he had learned to speak a few words, but with great difficulty. By age 6 he spoke only a little more. He cried a lot, had temper tantrums, and did not control his bowels or bladder. In many ways he remained like a baby. A visiting nurse called him ‘retarded’. Still lying alone in the corner, Enrique grew increasingly withdrawn. At age seven—if his mother understood him correctly—he asked her for a gun to kill himself.

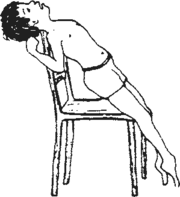

Soon after this, Enrique’s mother and his older sister took him to a team of village rehabilitation workers in a neighboring village. The workers realized that he would probably never have much control of his hands and legs. But he desperately needed to communicate more with other people and see what was going on around him, to be included in the life of his family and village. But how could he do this lying on his back? His mother had tried many times to sit him in a chair, but his body would stiffen and he would fall off or cry.

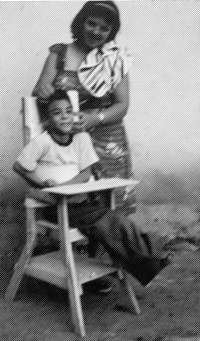

The village workers helped Enrique’s family make a chair for him, with a cushion and hip strap to help him sit in a good position. They taught his mother and sister how to help him sit in a way that would keep his body from stiffening so much.

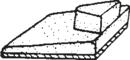

|

special cushion |  |

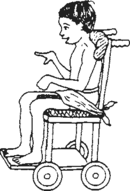

| Later, they added wheels to the chair. |

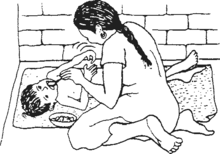

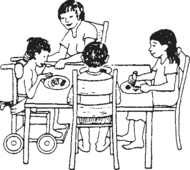

With his new chair, Enrique was able to sit and watch everything that was going on around him. He was excited and began to take more interest in things. He could also sit at the table and eat with the family (although his mother still had to feed him). Everyone talked to him and soon he began to talk more. Although his words were difficult to understand, he tried very hard. In time, he spoke a little more clearly. He also began to tell people when he had to use his toilet. He discovered he was no longer a baby, and did not want to be treated as one.

Every day Enrique’s sister and brother went to school. One day Enrique begged to go too, and they pushed him there in his chair. Soon he went every day, and began to learn to read. Enrique had begun to develop more control of his head. The village workers helped the teacher make a book holder attached to Enrique’s chair, and a head band with a wire arm so that he could turn the pages.

A happier and fuller life had begun for Enrique.

|

Enrique's sister helps position him in his new chair. |

Enrique’s story shows how development of the body, mind, and senses all influence each other. Enrique took longer to develop mentally because his mind did not have the stimulation (activity, exercise, and excitement) it needed to grow strong. He had almost no control of his body movements. However, his eyes and ears were good. When at last his body was placed so he could see and experience more of the world around him, and relate more to other people, his mind developed quickly. With a little help and imagination, he learned to do many things that he and his family never dreamed he could.

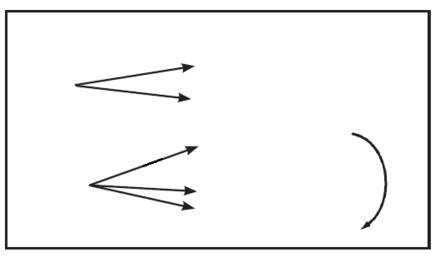

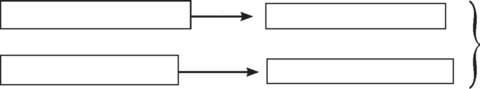

We saw how Enrique’s physical disability delayed his mental development. Similarly, a child with cognitive delay is often delayed in physical development. Development of body and mind are closely joined. After all, the mind directs the body, yet depends on the body’s 5 senses (sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell) for its knowledge of people and things. Therefore:

lead to

lead to

Each child, of course, has their own specific needs. Parents and rehabilitation workers can try to figure out and meet these needs. (An example is Enrique’s need for special positioning so that he can see and do things better.)

But all children have the same basic needs. They need love, enough good food, and shelter. And they need the chance to explore their own bodies and the world about them as fully as they can.

Early Stimulation

“Stimulation” means giving a child a variety of opportunities to experience, explore, and play with things around her. It involves body movement and the use of all the senses—especially seeing, hearing, and touching.

Early stimulation is necessary for the healthy growth of every child’s body and mind. For children without disabilities, stimulation often comes naturally and easily, through interaction with other people and things. But it is often more difficult for children with disabilities to experience and explore the world around them. For their minds and bodies to develop as early and fully as possible, they will need extra care and special activities that provide easy and enjoyable ways to learn.

The younger the child is when a “stimulation program” begins, the cognitive delay he will have when he is older.