Hesperian Health Guides

A Behavioral Approach to Learning and Improved Behavior

HealthWiki > Disabled Village Children > Chapter 40: Ways to Improve Learning and Behavior > A Behavioral Approach to Learning and Improved Behavior

Contents

Step 1. Observe the circumstances of your child’s behavior.

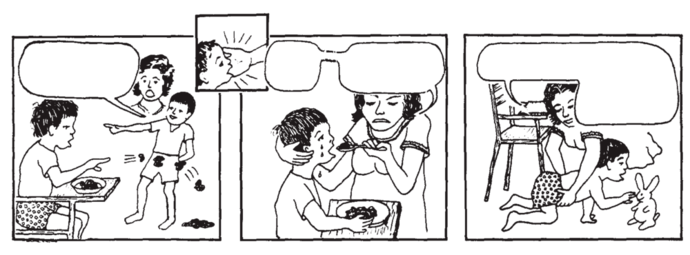

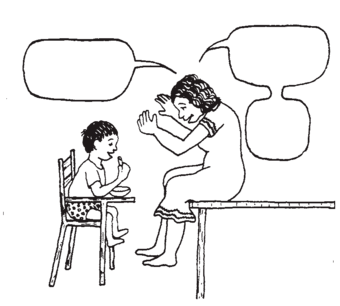

To help your child to behave more acceptably, start by carefully observing what is happening around and with the child when he begins his acts of disturbing behavior. Observe carefully for a week or two. To notice patterns more clearly, it helps to write down your observations. Try to make your records clear, specific, and simple. Take note of everything that might lead to your child’s acts of bad behavior, and what he seems to gain from it. For example, Raúl’s mother might write these notes:

MAH!

Here is your breakfast, Raúl.

MAH!

Marta and Pepe, please eat quickly. It is time for school.

Be still, Raúl!

I'm busy! MAH! | ||

| “I put him in his chair, and gave him food.” | “Then I got the older children ready for school.” | “He kept calling to me, but I was busy and told him to keep quiet.” |

Mama! Raúl's throwing his food again.

SMACK!

BAD BOY!

Now stop that crying and eat!

Raúl, don't ever throw your food again — or you'll

be sorry! Understand? | |||

| “Raúl began to throw his food!” | “I slapped him.” |

“He started crying. To quiet him, I fed him his breakfast.” | “Then I put him down to play with his toys.” |

Step 2. Based on your observations, try to figure out why your child behaves as he does. Look for answers to these questions:

- What happens that leads to or “triggers” his unacceptable behavior?

- Is his behavior partly due to confused or unclear messages from you or other persons?

- What satisfying results does his behavior produce that might make him want to do it again?

- Is the child’s behavior partly from feeling afraid or insecure?

By repeatedly observing what happened before Raúl began to throw food, his mother started to find some answers:

- “Raúl throws food most often when I leave him alone with it—especially when I am busy with the other children.”

- “My own messages to Raúl are confusing and contradictory. At the same time that I scold him, I also give him the attention and care that he wants—like feeding him as if he were still a baby.

- By throwing food, Raúl gets a lot of satisfaction.

POSSIBLE EXPLANATION FOR RAUL’S FOOD THROWING

| TRIGGERS | WHAT HE LOSES BY THROWING FOOD | WHAT HE GETS |

|

|

|

|

Step 3. Set a goal for improvement of the child’s behavior.

If the child has several different behavioral problems, it is usually best to try to improve one at a time. Be positive. Try to set the goal in terms of the good behavior that you want, not just the bad behavior that you wish to end. For Raúl, the goal might be “to learn to feed himself quietly” (not simply “to get him to stop throwing his food”).

Be sure that goals are possible for the child at his developmental level.

Step 4. Plan a way to help the child improve his behavior.

Consistently reward good behavior. Each time the child behaves as you want, immediately show your appreciation. Rewards can be words of praise, a hug, a special privilege (perhaps the chance to play with a favorite toy). Or give the child a bit of favorite food.

As much as possible, ignore rather than punish bad behavior. Rewarding good behavior rather than punishing bad behavior brings improvement with much less bad feeling for both parent and child.

Always reward good behavior and never reward bad behavior. This is the key to the behavioral approach.

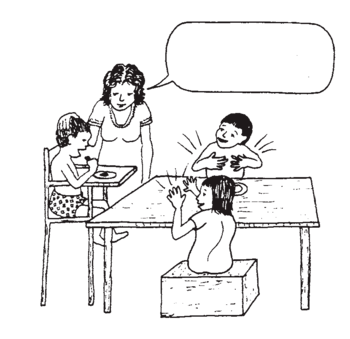

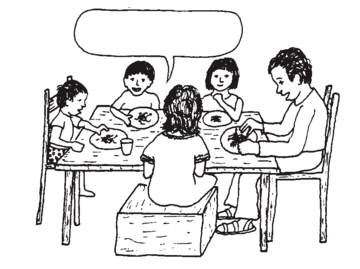

For example, whenever Raúl eats by himself, without throwing his food, the whole family can applaud and praise him.

| Raúl finds that good behavior brings rewards and attention. |  Good boy, Raúl. Now you can eat on your own like Marta and Pepe. |

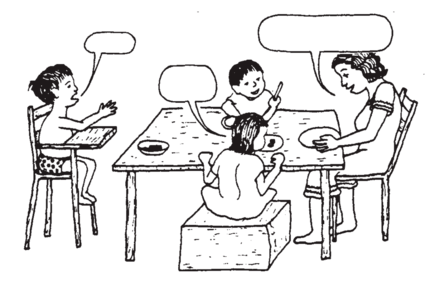

But whenever he throws his food, the family ignores him, except perhaps to say “I’m sorry you did that, Raúl,” or, “Once more and I’ll have to take your food away because I’m tired of having to clean up the mess.” (Make this a result, not a punishment.) Always do what you say you will do.

| He quickly learns that throwing his food now brings no reward. |  How was school today, Marta?

MAH!

Fine, Mama. |

ADDITIONAL GUIDELINES:

- Be consistent in how you respond to your child’s behavior. If you sometimes reward good behavior and at other times you ignore it, or if you sometimes ignore bad behavior and at other times either scold or do what the child demands, this is confusing. His behavior is not likely to improve.

- WARNING: When using this approach, at first the child may actually behave worse. When Raúl does not get his mother’s attention by throwing his food, he may try throwing his bowl too. It is very important that his mother not give in to his demands, but rather be consistent with her approach. Only if she is consistent will he learn that he gets more of what he wants with good behavior than with bad.

- Move towards the goal little by little, in small steps. If steps forward are small and clearly defined, often the child will learn more easily, and a beginning period of worse behavior can sometimes be avoided.

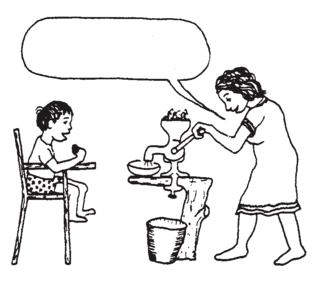

For example, it would be too much to expect Raúl to suddenly eat by himself quietly when mother is busy with the other children. Instead, mother can help him work toward this goal little by little.

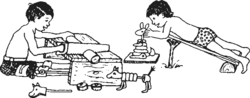

| A possible first step is for Raúl’s mother to give him his food after the other children have left for school. This way she can stay close to him as he eats it. | The next step might be for mother to do her work while Raúl eats, but to keep talking with him and praising him when he does well. | |

Good boy! I am proud of you!

Now take another bite.

Good for you!

|

Good boy, Raúl! What a big boy you are getting to be! |

In this way, Raúl will learn that eating by himself does not mean being left alone, but gets more attention from his mother than does throwing food.

Step 5. After the child’s improved behavior has become a habit, gradually move toward a more natural way of relating to the child.

| To help the child improve his behavior, the “behavioral approach” just described often works well. Your responses to your child’s acts are carefully planned and consistent. However, such a controlled approach to person-to-person relationships is not natural. Parents and children, like other people, need to learn to relate to each other not according to a plan, or because each action earns a reward, but because they enjoy making each other happy. |  Isn't it nice that we can all eat together now in peace! |

Therefore, the last step, after the child’s new behavior has been established, is to gradually decrease immediate rewards while sharing the pleasure of an improved relationship.

Setting reasonable goals—based on the child’s developmental level

Be realistic when setting a goal for improvement in behavior, or a new skill that you want your child to learn. First try to determine the child’s developmental level, and set a goal consistent with that level. (To determine the child’s developmental level, see Chapter 34, “Child Development and Developmental Delay.”)

Consider Erica, the girl who has tantrums (crying and screaming fits) whenever her mother puts her down. Erica has cognitive delay, which means she is developmentally behind for her age. Depending on her developmental level (not her age), her mother can plan steps to help her avoid tantrums:

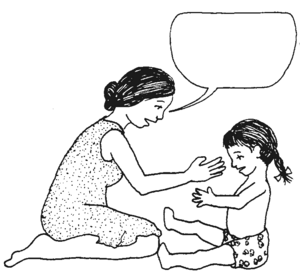

Suppose Erica is at the development level of a very young child. She has difficulty with hand control and no ability to play by herself, or to imitate (to copy) others. She will need to begin with very basic steps and clear, simple messages. Her mother can put her down briefly, then praise, talk, or sing to her as long as she does not have a tantrum. When she does have a tantrum, her mother should try to give her as little attention as possible, and never give in to her demands. She can pay attention and reward her during those moments when she stops screaming—if only to catch her breath. This way Erica will begin to learn that she gets more of what she wants through good behavior than through tantrums.

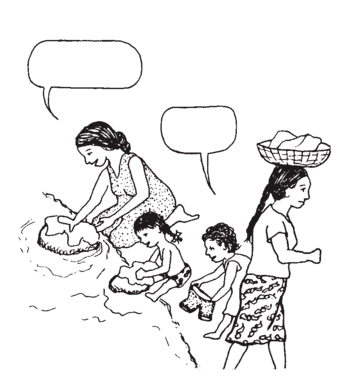

Now suppose that Erica is at a more advanced level of development. She likes using her hands and imitating her mother. Steps for improving her behavior can start from this level. Perhaps her mother can have Erica sit at the river’s edge and pretend to help her mother wash clothes. This way Erica will feel closer to her mother and will be less afraid of being left alone. Her mother can talk to her and praise her all the time.

Note: At this level, Erica will not be able to stay with one activity for very long. To avoid tantrums, her mother will need to keep the activities interesting by changing them often, and talking to her a lot. In all of this, other children can be a big help.

|

| Giving lots of attention, encouragement, and praise when he makes an effort is one of the best ways to help a child learn new skills. Photo by Sonia Iskov from Special Education for Mentally Handicapped Pupils |

Helping the child make sense of his world

The behavioral approach to learning and development that we have discussed is similar to what is called “behavior therapy” or “behavior modification.” However, we prefer to put the emphasis on improving communication to help the child make sense of the world around him. Instead of our changing the child’s behavior, we would rather help the child to understand things clearly enough so that he chooses to act in a way that will make life more pleasant for everyone. (This is the point of view in Newson and Hipgrave’s Getting Through to Your Handicapped Child, from which many ideas in this chapter are taken.) To achieve this, parents first learn to understand and change their own behavior in relating to their child. They look for ways to communicate with the child that are consistent and supportive, and that reinforce good behavior. A behavioral approach can often help children with cognitive or developmental delays, such as Raúl and Erica, to relate to other persons better and to learn basic skills more quickly.

The approach can be used at almost any age. It is often easier with younger children (developmental age from 1 to 4). Starting at a young age can prevent small behavioral difficulties from becoming big problems later. For the very young or child with severe cognitive delay, goals must be kept basic, and progress toward the goals must be divided into small steps. To master each step, much repetition may be needed with consistent praise and rewards for each small advance.

Children with physical disabilities and typical cognitive development sometimes also develop unacceptable patterns of behavior. A behavioral approach may help them also. The story below tells how this approach helped Jorge to behave better.

Jorge a 10-year-old who had polio that caused paralysis of his legs. He lives with his grandmother. He is noisy, rude, bad tempered, and whenever he plays with other children, it turns into a fight. Jorge has caused so much trouble in the classroom that his teacher recently told his grandmother he will throw Jorge out of school if he does not change. Both his teacher and grandmother have tried scolding him and whipping him, but it only seems to make Jorge’s behavior worse. As his grandmother says, “He loves to make people angry at him.”

Jorge is an intelligent 10-year-old whose legs are paralyzed by polio. He lives with his grandmother. He is noisy, rude, bad tempered, and whenever he plays with other children, it turns into a fight. Jorge has caused so much trouble in the classroom that his teacher recently told his grandmother he will throw Jorge out of school if he does not change. Both his teacher and grandmother have tried scolding him and whipping him, but it only seems to make Jorge’s behavior worse. As his grandmother says, “He loves to make people angry at him.”

Not long ago, Jorge’s grandmother took him to the village rehabilitation center to ask for advice. A rehabilitation worker helped her to observe both Jorge’s and her own behavior more closely to better understand why Jorge acts the way he does. She realized:

- When Jorge is quiet and well-behaved (which is not often), everyone ignores or forgets him.

- As a result, Jorge feels unwanted, unloved, and useless. Starved for emotional human contact, he gets it by making people angry with him.

- Jorge’s bad behavior, therefore, brings him a lot of person-to-person contact, even though it is painful. The few times he tries to be good, he is made to feel unwanted and unneeded.

“I really do love him,” said his grandmother. “But I guess I don’t show it much. He makes me worry so much!”

To begin to behave better, Jorge needed to find out that friendly and helpful behavior can bring him closer to people than bad behavior. For this reason, the village worker—together with the grandmother, the schoolteacher, the schoolchildren, the rehabilitation team, and Jorge himself— helped figure out ways that would let the boy see that good behavior is better than bad behavior.

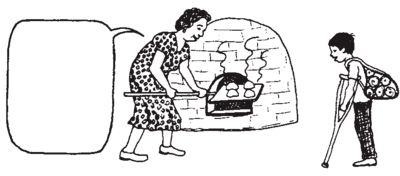

At home, grandma began to look for things Jorge could do to help her, and to show him how happy she was when he did them. She made a backpack, open at the sides, so that he could help bring firewood. Also, she learned to quietly turn her back when he misbehaved, and to let him know how happy she was when he would sit quietly doing his homework or shelling the maize.

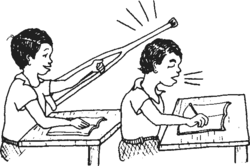

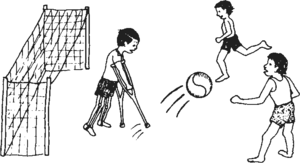

At school, the teacher discussed with the other children ways to include Jorge in their games. When they all played football (soccer), they let him be goalie. To everyone’s surprise, Jorge was an excellent goalie. With his crutches he could reach farther and hit the ball farther than anyone else. Soon all the children wanted Jorge to play on their team. At first Jorge started a few fights. But when he did, he was quietly asked to sit on the sideline. Soon he learned to stop hitting other children so that he could keep hitting the ball.

In the village rehabilitation center, the village worker invited Jorge to help make educational toys for children with and without disabilities. He helped Jorge get started and praised him for each toy Jorge completed. Soon Jorge learned to make the toys by himself and took great pride in his work. When he saw other children with disabilities playing and learning things with his toys, it made him very happy. He decided he wants to be a rehabilitation worker when he grows up.

“Time Out” or “non-reward” instead of punishment

The story of the way family and friends used the behavioral approach to help Jorge sounds fairly straightforward and simple. But in real life it is seldom that easy. “Bad” behavior may sometimes be so bad that it cannot be ignored.

In general, the best way to make bad behavior seem boring to the child and not worth the trouble is to give no rewarding response. At the same time, make sure to reward good behavior. This means everything satisfying stops as a result of bad behavior (instead of the usual situation where everything satisfying starts).

For example, when Raúl throws his food, instead of entertaining him by scolding and feeding him, his mother should remove both the food and herself for 3 or 4 minutes— making the situation as boring as possible.

Removing food may seem like punishment. But it is best to aim at making the situation less interesting rather than making it unpleasant. To make things less interesting, sometimes we may remove the child from the situation for a brief time. This is often called time out.

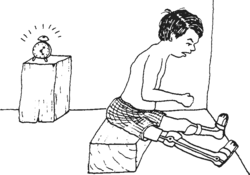

For example, when Jorge’s grandmother first began using the behavioral approach, to try to make her angry he would shout and hit the chickens with his crutches. But instead of her usual scolding, grandma now simply told him that if he did not quiet down she would ask him to take time out in the corner. Then, if he continued to make trouble, she would lead him to the corner and tell him that he would have to stay there for 5 minutes from the time he was quiet. She set an old alarm clock to ring in 5 minutes. At first Jorge would continue to shout from the corner, but each time he did, grandma would set the alarm to ring in another 5 minutes from the time he was quiet. Meanwhile she gave him no attention and continued her work.

In this way Jorge learned while he was in the corner that the only way to make life interesting again was to stop making a disturbance.

We should try to use time out as a “non-reward” and not a punishment. However, because time out is something an adult makes a child do, it can seem like punishment. Try to use it only when less forceful methods of avoiding rewards do not work. It is best to start with a time out period of no more than 5 minutes (less for a very young child). If the child does not behave better in 5 minutes, consider with the child adding another 5 minutes. Never leave the child in time out for more than half an hour, even if he has still not become quiet.