Hesperian Health Guides

Sanitation for Cities and Towns

HealthWiki > A Community Guide to Environmental Health > Chapter 7: Building Toilets > Sanitation for Cities and Towns

In cities and towns, health problems can spread very quickly. It is difficult to improve sanitation services in crowded cities and towns without a lot of help from governments, NGOs, and other partners. This book can offer only some guidelines to help think about possible solutions.

The main barriers to good sanitation services in cities are:

- physical. Often, sanitation is considered only after neighborhoods and settlements have roads, electricity, and water. Yet once a city is built, it is much harder to plan for and build toilets and sewage systems.

- economic. Sewage systems and public toilets are costly to build and maintain. If there is little government support, it is difficult to afford sanitation.

- political. Local governments may not want to deliver services to informal settlements and poorer neighborhoods. And there may be laws that prevent people from planning and building their own toilets and sewage systems.

- cultural. People and officials in cities often want flush toilets and costly sewer systems, making it difficult to agree on more sustainable and affordable alternatives.

Creative solutions for healthier cities

Any kind of toilet, including the ones in this guide, can be built and used in cities. And if sanitation services are combined with parks, urban farming, resource recovery and recycling, and clean energy, cities can become healthier and more pleasant places to live. When city governments work with neighborhood groups to come up with creative solutions, the result will be cleaner, healthier cities.

Urban community sanitation

Not long ago, Yoff was a typical West African fishing village outside of Dakar, the capital city of Senegal. Families lived in compounds connected by walking paths and open spaces. But as Dakar grew and swallowed Yoff, it became part of a large urban area with an international airport and a lot of automobiles.

As the town grew, many houses installed flush toilets connected to open pits where the sewage sat and bred disease. Other people, too poor to afford toilets, used open sandy areas. But with many people living close together, this quickly became a health problem.

A town development committee came together to solve the sanitation problem. They began by looking at the resources they had: strong community networks, skilled builders, and people committed to keeping village life. They also had some new ideas about ecological sanitation.

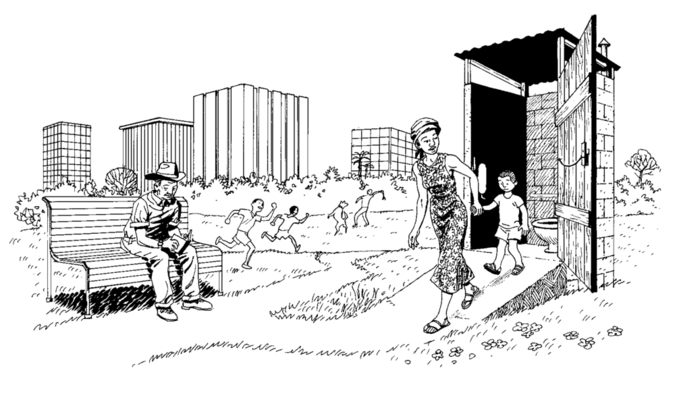

In the village, houses were grouped around open common areas where people could gather and talk. After talking to many villagers, the committee made a plan to use this open area for a sanitation system that would make the area more attractive, rather than uglier. Instead of promoting household toilets and underground sewage tanks, they would promote community ecological sanitation.

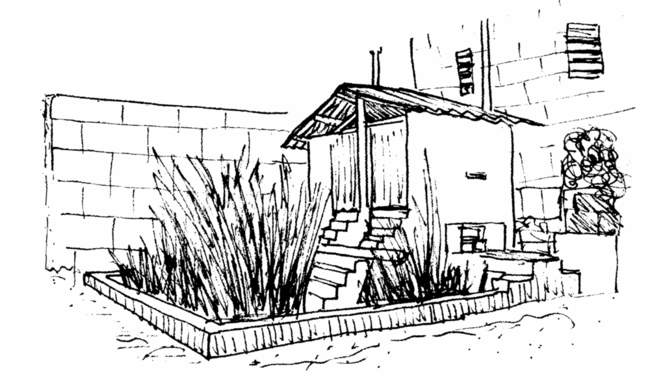

The committee worked with residents to build urine-diverting dry toilets. Each set of toilets would be shared by the whole compound. The urine would run through pipes into beds of reeds. The feces, after being dried out, would be used to fertilize trees. All of this would help to keep the village green. Local masons and builders were hired to construct the toilets and to maintain the common areas.

This urban sanitation project not only prevented health problems, it helped to preserve the way the people of Yoff wanted to live.