Hesperian Health Guides

Planning for Toilets

HealthWiki > A Community Guide to Environmental Health > Chapter 7: Building Toilets > Planning for Toilets

|

| A plan that leaves women or anyone else without toilets will not prevent illness in the community. |

Every person and every community has a way of managing human waste, even if it just means that people go into the bush or forest to urinate and defecate. Not all people in a village use the same method, and not every person disposes of their waste the same way all the time. Some people may want to change, while others may not. Whether it means building a new kind of toilet, improving access to safe toilets, or some other kind of change, almost every sanitation method can be improved.

Small, step by step changes are easier than big changes all at once. Examples of small changes that can have a big impact on health, safety, and comfort are:

- keeping wash water and soap near the toilet.

- adding a screened vent to a pit toilet to let air flow and also trap flies.

- adding a durable platform to an open pit.

When planning or making changes in the way human waste is disposed of in your community, keep in mind that every method should:

- prevent disease — it should keep disease carrying waste and insects away from people and food, both at the site of the toilet and in nearby homes.

- protect water supplies — it should not pollute drinking water, surface water, or groundwater.

- protect the environment — toilets that turn human waste into fertilizer (ecological sanitation) can conserve and protect water, prevent pollution, and return nutrients to the soil.

- be simple and affordable — it should be easy for people to clean and maintain, and to build for themselves with local materials.

- be culturally acceptable — it should fit local customs, beliefs, and needs.

- work for everyone — it should address the health needs of children, women, and men, as well as those who are elderly or disabled.

Sanitation decisions are community decisions

When decisions about toilets are made by the people who will use them, it is more likely that people's different sanitation needs will be met. And because household, neighborhood, and village sanitation decisions can affect people downstream, when neighboring communities work together, health can improve for everyone.

Community participation can make the difference between success and failure when a government or outside agency tries to improve sanitation.

The wrong toilets?

In 1992, the government of El Salvador spent over US $10 million to build thousands of toilets. These toilets were meant to turn waste into fertilizer, but they needed more care and cleaning than the old toilets people were used to. The government did not involve anyone in the communities to help build them, and there was no training in how to use them. So people did not learn how they worked.

After the project was finished, the government studied how the toilets were being used. They learned that many of the toilets were not being used well, and others were not used at all.

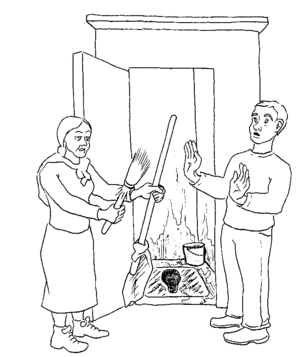

Someone must clean the toilet

No one likes to clean the toilet. But someone has to do it.

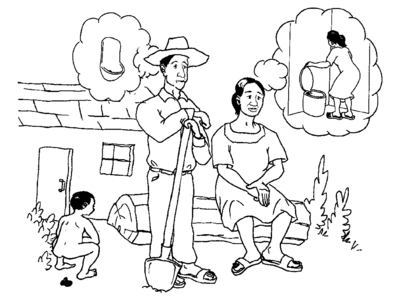

Often, the job of planning, building, and fixing toilets is considered men’s work or work for specialists. The less pleasant and more constant task of cleaning toilets often falls to women or people of lower social classes. It is unfair if tasks that are unpleasant always fall to women and poor people who usually do not make the decisions in the first place.

Sharing unpleasant tasks is a way to make sure the work gets done, though it often creates social conflicts.