Hesperian Health Guides

Safety at Mine Sites

HealthWiki > A Community Guide to Environmental Health > Chapter 21: Mining and Health > Safety at Mine Sites

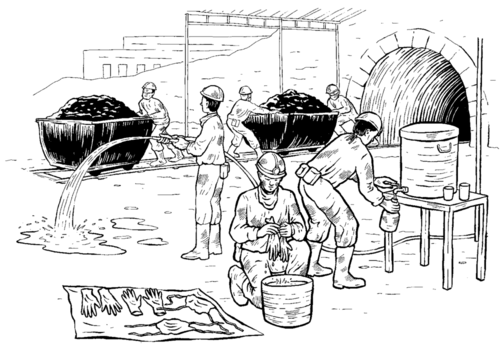

Workers and communities need the right to protect themselves from harm, information, and equipment and training to reduce exposure to harmful materials. Miners and communities often form safety committees to make sure conditions are as safe as possible. Safety committees can also prepare for emergencies with plans to transport hurt workers and evacuate anyone in danger.

Mine operators should provide protective equipment for all workers and maintain it in good condition. Mine operators should also make sure every mine operation has first aid supplies, and that all workers have access to them (see Appendix A). Most importantly, all workers should be trained about mining dangers, such as chemicals, using explosives, and landslides.

To make sure mining does as little harm as possible to the environment, communities and their allies should monitor water and air near mine sites for signs of pollution. People who may be exposed to toxic chemicals, excessive dust, or other dangers should be tested by health workers on an ongoing basis, and be given treatment at the first signs of health problems.

Contents

Organizing to improve miners’ lives

|

| Miners know that by working together, we can move mountains! |

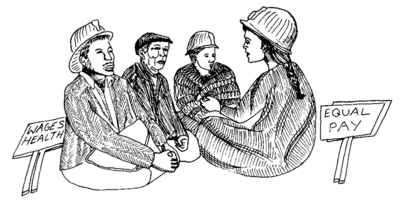

Miners around the world have improved their lives, safety, and health by forming labor unions and cooperatives, and by pressuring mining companies to obey laws and the government to enforce them. They have also organized campaigns to enforce international treaties to regulate mine health and safety. Miners and others have also used strikes, demonstrations, and blockades to stop mining operations when they are unfair, unsafe, or destructive to the environment.

Women miners organize a cooperative

In Bolivia, women collect scraps of gold, silver, and tin from waste piles dumped near the mines. Many women are forced to do this difficult work after their husbands die in mining accidents or from silicosis. The women work long hours, often in contaminated water, and with no protection. They earn very little money. In the past, they were not even recognized as workers by the government. They were like invisible people.

One day, a mining company began blasting a road through the waste dump where a group of women were working. The women climbed to the top of a hill to protest the destruction of their only source of income. They were not able to stop the blasting, but they continued to fight for their rights.

They formed a cooperative to demand more money from the companies who bought their scraps. The companies refused to pay more. But the government recognized their struggle and passed a law that made the companies pay the women when they missed work because of illness. This was a small step, but it was the first time the women’s work was recognized by the government. This small victory inspired the women and other mine workers to continue building cooperatives and unions, and organizing for justice.

Holding corporations accountable

Many mining operations are run by multinational corporations whose headquarters are in countries far from the mine site. This makes it difficult to pressure them for change. But people around the world have organized and forced corporations to change their practices and even to abandon mining projects.

Asbestos miners finally win in court

When Audrey was a child, she worked at a mine in South Africa for the Cape Mining Company of Britain. Her job was to step up and down on piles of asbestos powder so that it could be packed into bags for shipping. A supervisor watched her and the other children to make sure they never stopped working. If she stopped, he would whip her. Audrey became very sick from breathing in asbestos, and so did many other workers.

Thirty years later, Audrey joined thousands of other South Africans to sue the British company for causing her health problems. The company spent 3 years arguing that the South African courts should hear the case. Audrey and the people she worked with believed a South African court would not give them a fair trial against a big company that brought a lot of money into the country. Audrey and others traveled to other countries to tell people about their struggle and win support. Finally the courts agreed to hear the case in Britain, the home base of the asbestos company.

After almost 5 years of legal battle, the company gave up. They paid the miners tens of millions of dollars for the harm they caused. Today, most countries ban asbestos mining and many countries ban the use of asbestos altogether. Finally in 2008, South Africa went from being one of the world’s largest producers of asbestos to prohibiting the use or manufacture of asbestos or any asbestos product.