Hesperian Health Guides

Health promoters stop cholera

HealthWiki > A Community Guide to Environmental Health > Chapter 1: Promoting Community Environmental Health > Health promoters stop cholera

Day after day, people brought family members to the local health center in the town of Manglaralto. They were weak, trembling, feverish, and suffering from terrible, watery diarrhea and dehydration (loss of too much water in the body). The health promoters realized this was a cholera epidemic and many people would die if they did not act quickly to stop it.

Because cholera contaminates drinking water and passes easily from one person to the next, the health promoters knew that treating the sick people was not enough. To prevent cholera from spreading, they would have to find a way for everyone in Manglaralto and the nearby villages to have clean water and safe toilets.

The health promoters began to organize the villagers who were still healthy, and they asked local groups for help. They persuaded an organization that had partners in other countries to give money to start an emergency program to provide clean water and toilets.

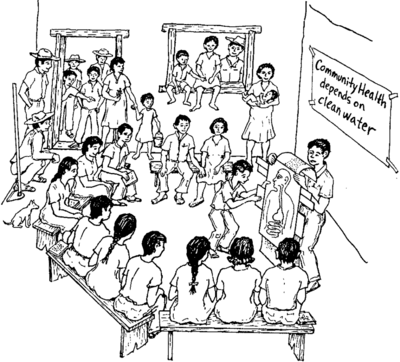

Calling their project Salud para el Pueblo ("Health for the People" in Spanish), the health promoters organized public health committees in every village. Committee members selected "village health educators" who were trained to teach people about water and sanitation (building and maintaining toilets and washing hands to prevent the spread of germs). In this way, the health promoters enabled the villagers themselves to take responsibility for important parts of the fight against cholera and for environmental health in their communities.

Contents

Working together for change

The first thing the village health educators did was teach people how cholera and other diseases that cause diarrhea can spread. Then they helped each household and each village make sure its water supply was clean. They also taught people how to stop dehydration, the main cause of death from diarrhea, by making a rehydration drink of sugar and salt in boiled water and giving it to children and anyone else who had diarrhea. They taught people in schools, churches, community centers, and public gathering places to prevent cholera by washing their hands and by building and using safe toilets. After a few weeks, the cholera had nearly disappeared.

But the health promoters knew they had more work to do to make sure cholera would not strike again.

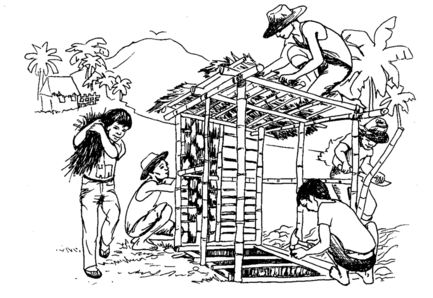

With help from local engineers, people came together to build piped water systems, to improve pit toilets in every village, and to make sure every household had enough water for bathing. The villagers themselves did the work, and learned how to clean and maintain the water systems and toilets. They also made sure animals were fenced in (to keep animal wastes out of the water supply) and that water containers were covered to prevent disease-carrying mosquitoes from breeding.

As this work went on, people from other villages joined in. Starting with 22 villages, Salud para el Pueblo reached 100 villages not long after it began. Soon there was no cholera in the entire region, and other illnesses had been reduced as well.

What made this health organizing successful?

Salud para el Pueblo was very successful at stopping cholera and moving on to solve other problems. This happened because the health promoters:

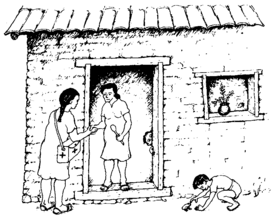

- worked with people in their homes. Salud para el Pueblo workers trained people house by house to keep their water supply clean. This helped the health teams learn about other problems and gain trust in the community.

- brought many groups together. Local organizations, local government, national and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the Ministry of Health all worked together. This made sure all of their resources and experiences were available to help stop the epidemic. Because they worked together, they avoided the problem of one organization doing the same job as another organization, or working against one another.

- valued people as the most important resource. They did not blame the villagers for the health problems, and they did not depend only on help from outside the communities. Instead, they used the peoples' own experience to work toward a common goal. They used games, puppets, songs, discussions, and popular education activities to bring people together to share their knowledge and abilities. These activities built self-confidence and motivation as the villagers saw how their own knowledge and participation solved serious health problems.

How the vision of environmental health began to grow

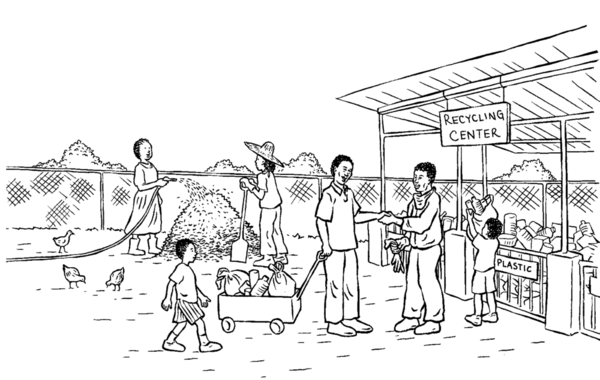

Over time, the health promoters also realized disease-carrying insects were breeding in trash and trash dumps. They held community meetings about the need to clean up the streets and to improve the dumps. Each village formed a group of "environmental health promoters" who organized work days for everyone to pick up trash. With help from an engineer, the environmental health promoters turned waste dumps into safe pits called sanitary landfills. Over the next few years, the promoters talked about starting a recycling program to reduce the amount of trash in the landfills. When an international agency donated a big truck to haul trash to the regional recycling center in the city, they were able to do just that. The money earned from recycling helped pay for gasoline and the costs of maintaining the truck.

By 1996, Salud para el Pueblo had built hundreds of toilets, installed many piped water systems, dug 2 sanitary landfills, started a recycling program, and began to help people plant community gardens.

Then in 1997 disaster struck. The rainstorms known as El Niño hit the coast of Ecuador. For 6 months there were strong winds and rain nearly every day. The winds tore up the trees, rain turned the hills to muddy landslides, and the valleys filled with raging brown rivers. The rivers overflowed and changed course, destroying whole villages. Toilets, water pipes, and years of hard work were washed away.

As the hills collapsed, the work of Salud para el Pueblo nearly collapsed with them. To better understand why this happened, we must look at the history of the region.

A hill with no trees is like a house with no roof

|

| before |

|

| after |

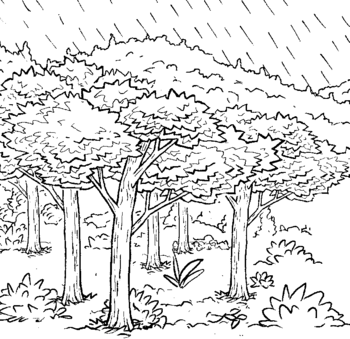

The hills and mountains on the coast of Ecuador were once covered in thick tropical forests. Mangrove trees grew where fresh water from the rivers mixed with salt water from the sea. The mangroves protected the coast from storms and were home to many kinds of fish and shellfish. Bamboo trees grew along the streams, keeping their banks from being worn down or washed away (erosion). Forests were filled with giant ceibo trees that gave shade. Their deep roots held water and soil. Carob trees grew on the steep mountain slopes, holding the soil in place and keeping the hillsides from falling down. Leaves from the trees enriched the soil when they fell to the ground.

The forests were home to people, and also to deer, birds, insects, lizards, and countless other animals. People built their houses out of bamboo and palm tree leaves. There were animals to hunt, wild berries to eat, and water and rich soil for gardens and small farms.

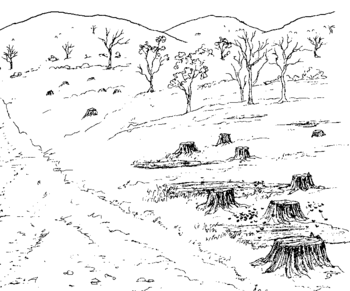

But over the last 100 years, many of the trees were cut down to make a railroad and to build houses. Then a company from Japan came and cut down most of the remaining trees, using the railroad to carry the wood to a port on the coast, and shipped it to Japan. Because tropical forest trees are very strong, they sold for a good price. When the trees were gone, the company left. The railroad fell into disrepair. Over time, it was abandoned.

Now, the mountains on the coast of Ecuador look like a desert. The hills are brown and there is no shade. In the dry season, the soil blows away and the air is full of dust. In the rainy season, the soil turns to mud and the hillsides tumble down. When the El Niño storms came in 1997, there were no trees to protect the villagers from their destructive force.

Finding the root cause of the problem

When they saw how the rains washed away whole villages — taking the new piped water systems and toilets with them — the health workers of Salud para el Pueblo realized they needed to do different kinds of work to prevent disasters like this in the future. Building water systems and promoting safe sanitation only solved one part of the problem.

There is a saying in the villages: a hill with no trees is like a house with no roof. This means trees protect the hills and prevent them from being eroded in the wind and rain, just as a roof protects the people in a house. The health workers began to see promoting tree planting and protecting natural resources was as important as promoting health — because they are one and the same!

With this in mind, the health promoters started a tree-planting project. But some villagers did not want to plant trees. One man named Eduardo refused to join the tree-planting project.

"Too much work," Eduardo said. "They just want us to work for nothing." He convinced some other villagers to go against the health promoters.

were the trees cut?

By asking "But why?" questions, Gloria helped the villagers look at all the ways their health problems were related to their environment. At the end of the discussion, most of the villagers agreed it was important to plant trees to prevent erosion and protect the soil. But Eduardo was still not convinced.

Learning to be an effective environmental health promoter

Gloria returned to the health center discouraged. "Even though they understand the importance of trees, they still will not do the work to plant them," she thought. "How can I convince them?" Just then, a bee flew into the room and startled her. Gloria shooed it away, and then saw it fly out the window and land on the red flower of a carob tree. This gave her a new idea.

The next day, Gloria gathered the villagers together again. She asked another question, and Eduardo was the first to answer.

The other villagers thought hard, and this is the conversation that they had:

Gloria said, "If we grow trees with flowers that bees like, we can start a beekeeping project and sell the honey. It will take only 1 year for the flowers to blossom." The villagers liked this idea. Even Eduardo agreed to try planting trees if he could learn how to produce honey.

Eduardo stopped Gloria as she was leaving. He told her, "When my grandson was sick with diarrhea we made him a drink from the pods of the carob tree. It cured him better than any medicine from the doctor. I think it would be a good idea to plant carob trees. Then we can make the curing drink and use the honey we produce to make it sweet."

Gloria returned to the health center excited about these new projects. After thinking about how the meetings had gone, she realized it would never work for her to tell the other villagers what to do. She had to learn to hear their ideas and understand their needs if she was to be an effective environmental health promoter.