Hesperian Health Guides

Who designed the factories and the jobs?

HealthWiki > Workers' Guide to Health and Safety > Chapter 1: Working for a living and living well > Who designed the factories and the jobs?

It is the responsibility of the factory owner to make sure the workplace is safe, and that all jobs are safe jobs. If the boss does not have the expertise to do that (and most do not), he can hire occupational safety and health (OSH) professionals to oversee conditions in the workplace. Many factories have health and safety departments, and worker and management safety committees, to constantly monitor and hopefully improve workplace conditions. When the people in these positions are committed to protecting worker health, they can be a huge force for change.

But the global companies who contract the factories have already won the "race to the bottom." They usually do not leave local factory owners a lot of room to improve conditions, increase wages, or make changes. The brands have an iron grip on the global factory system. That is why it is so important for workers to make alliances with consumers who want a fair and sustainable system, and with governments and occupational safety and health professionals who want to protect peoples’ health and safety.

Chakriya’s story

Chakriya moved from the countryside into Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital city, to work in a garment factory. She quickly found a job at Song Industrial, a company that makes clothes for international brands. She and her baby son moved in with Veasna, a woman from her village, in a tiny room in the Canadia slum near the factory. The minimum wage Chakriya earned was barely enough to pay for food and rent. To send money to her parents and sisters, she had to work lots of overtime.

The minimum wage in Cambodia is not enough to live with health or dignity. This makes life very hard for workers and their families, but it is why the brands come to countries like Cambodia in the first place. International companies contract with Cambodian factories because they are the cheapest. When factories compete to offer the lowest price, rarely do they invest in protecting workers’ health and safety.

The factory where Chakriya worked was very hot. The air felt like an oppressive, steamy cloud that never moved. One day in a very busy week, Chakriya noticed a sweet, sickly chemical smell that made her head spin. Then she fainted. A truck took her and 2 dozen other workers who had fainted to the hospital. More than 2,400 Cambodian garment workers faint at work each year, but the industry says they don’t know why.

The factory owners blame the mass fainting spells on the workers, saying they are hysterical women who feed off each other’s mental health problems. But Chakriya doesn’t think the problem is in her mind. "We work too many hours and we are just too tired. Our salaries are not enough to buy food. And if we buy food, we cannot pay our children’s school fees. And there’s nothing left to send home to our parents."

One day, the boss called the workers together. Some foreigners spoke about how the ILO Better Work program had made an agreement with their factory to improve conditions. Soon the lighting and ventilation were improved, but the wages stayed the same. That was the last time Chakriya heard of Better Work and the only time the factory got any better.

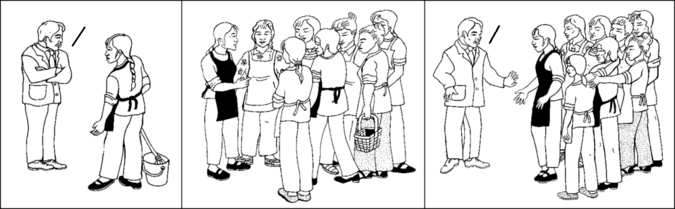

Chakriya had joined a union at her factory hoping that by acting together the workers could get higher wages and better conditions. The union joined a general strike over wages in 2010, and 68,000 workers stopped work for a week. The company immediately fired 160 active union members. The union organized workers to work slower, to refuse overtime, and to complain about the condition of their machines until the company rehired the union members. After 5 months, the fired workers got their jobs back. But the factory still didn’t increase wages.

At the end of 2013, the workers couldn’t take any more. They demanded that the minimum wage double, from $80 to $160 a month, a basic "living wage" that would let workers pay rent, eat nutritious food, and care for their families. But the government, pressured by the factory owners, only raised salaries to $95 – not enough! The workers walked out in a general strike that lasted almost a month.

This time the government responded violently. Police attacked workers, and killed 4. Many people fled to their villages because they were scared. Finally, hunger and repression drove the workers back to their jobs. 23 protesters were jailed for 5 months.

The struggle of Cambodian garment workers did not go unnoticed. International unions, the ILO, NGOs from Europe and the US, and even some responsible brands began to pressure the Cambodian government and factory owners to improve conditions. Most important, the Cambodian workers stayed united and strong, and in November 2014 they won another increase to the minimum wage.

Chakriya still earns too little and works too hard in bad conditions. But the gains she has made with her union, and the alliances her union has made internationally, have shown that getting organized and working together for change is necessary to make things improve.