Hesperian Health Guides

Chapter 3: Serious mental illness

Examples of serious mental health illnesses include:

- severe depression

- bipolar disorder, when someone alternates between being very depressed and very keyed-up (manic)

- post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), when past traumatic events cause a person’s body to be in a constant state of alert or numbness

- psychosis, a disconnection from one’s surroundings and being in a different reality than others experience

- schizophrenia, a type of psychosis, which interferes with the perception of reality, the organization of thoughts, and the ability to have a full range of feelings

Our society’s lack of openness about mental health creates stigma and discrimination for people with mental illness. Some people won’t talk about it or even use the words “mental illness.” This does not help.

A basic understanding of mental illness can help you connect someone who needs support to a doctor, counselor, or community clinic, and to provide support yourself. Unfortunately, health systems in the US make getting respectful, helpful, and affordable care very difficult, if not impossible. Options are so limited that the choice can be between insufficient care or being locked up. Psychiatric drugs may work well for some people but create even more problems for others. Health insurance may sometimes cover costs of mental health treatment, but there can be long waiting lists and limited treatment options. People of color often find mental health providers to be culturally inappropriate and insensitive to the stress and trauma caused by racism. Too often, these barriers prevent us from getting the care we really need and instead we just accept what we can get.

The chances of getting quality and long-term care for mental health in the US are so bad that medical professionals, news media, and even politicians are seeing the situation as a crisis and calling for action. Progress so far is due to the many dedicated individuals and organizations working to reduce the inequalities and conditions that cause mental health problems and limit treatment. This momentum opens a space for you and your community to mobilize to address the most pressing mental health needs and help construct this movement for change.

Contents

Treatment with medicines

When they work well, psychiatric medicines can calm people, make them feel less anxiety, allow them to concentrate and feel productive, and ease distress in a variety of ways. But like other medicines, sometimes they have too strong of an effect, side effects causing new problems, or even the opposite effect of what is intended. Some people believe that these medicines are the only thing that allows them to lead a “normal” life. Others find the medicines harmful, saying that they deny them access to their feelings and their genuine self.

Medicines are sometimes used as a quick fix instead of full-time accompaniment, intensive talk therapy, or community building among people with mental illness. If integrating different approaches was better supported through funding, policies, and medical education, such treatments could lessen the use of psychiatric medicines and their unwanted effects. But when other treatment approaches lack social supports and are unavailable or unaffordable, patients and their families and friends are left with very difficult decisions.

When a mental health provider prescribes a medicine and the person agrees to use it, it may take some time to find the right medicine and best dose. It can also take time for the person to get used to the medicine’s effects. Which medicines are available or a person’s needs can change over time. Many people find it helpful to involve a close friend or relative while trying out medicines. This other person can check in about how the medicines are working, what side effects are happening, and what to do if a medicine does not work well.

Using psychiatric medicines does not change a person’s need for a supportive community, regular meals, exercise, and stable housing. If more people could live without worrying about these basic needs, it would prevent at least some serious mental health illness. Addressing them should always be part of helping people heal and have stability.

Community awareness and support

Mental illness is a community issue, especially because of stigma, discrimination, exclusion, and the lack of understanding that leads to people with mental health concerns being penalized, isolated, mocked, or feared. Similar to other types of disabilities, as a society, we need to make more room for people with mental illness to participate fully in social life, make contributions, and live in the least restrictive way that is safe.

Story of the new neighbor

A new neighbor moved into a house in a small rural town. He spent a lot of time on his front porch, so many people greeted him and exchanged small talk. Neighbors commented that he was a little mysterious, but perfectly nice. Then one night, he took a hammer and broke the windows of the cars parked near his house.

Someone called the police and he was arrested. Some of the neighbors whose cars had been damaged attended the court proceedings a few weeks later. They learned that their new neighbor had bipolar disorder and had stopped taking his medication, which led to his drastic change in behavior.

The man’s parents, who lived a few hours away, arrived to support their son. The parents had hoped that quiet, small-town life would be a good environment for him and help provide the stability he needed to stay on his medications. The townspeople decided to give their new neighbor a second chance and talked with him about how they could work together to prevent this from happening again.

He said he would be OK with having regular check-ins with two neighbors to see how he was doing. He agreed to give them contact information for his parents and his doctor. Understanding more about his situation and finding out what he found helpful and unhelpful, community members set the stage for ongoing support that would hopefully prevent another crisis, avoid the police, and keep him out of jail.

By talking about and preparing for mental health challenges as part of everyday life, we show anyone experiencing them that they are not alone, they will not be discriminated against, and they don’t have to hide their situation. This means establishing new habits in our communities and workplaces to make them more welcoming to people with mental health challenges—which at some point or another, includes all of us.

There are probably people in your life, community, or workplace who have, or previously had, a serious mental illness. They may be managing their illness so well that unless they tell you, you would have no way of knowing.

If someone in your workplace or community lets you know they have a mental health condition, you can ask if this is something the person wants others to be aware of, and if it causes them any barriers to full participation. Without assuming that they need help, invite them to let you know if there are any supports or accommodations that would be helpful.

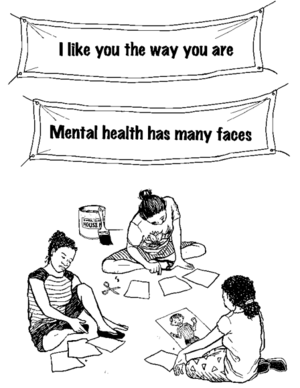

Community-based art to challenge stigma and create connections

Stigma in US society makes living with mental illness so much harder than need be. The multi-year NYC Mural Arts Project brought the experiences of people living with mental health conditions to New York City neighborhood walls while creating connections. Each mural involved a group process putting people with mental illness at the center of lively art-making workshops with friends, family, and neighbors. Each workshop series was hosted by a community-based group—a mix of schools, job readiness programs, public housing resident associations, and others.

To come up with mural themes, community sessions were led by a mural artist and one or more Mental Health Peer Support Specialists—people living with mental health challenges trained to support others in the same situation. They discussed community challenges, needs, and desires to craft the mural’s message while forging new relationships among participants. The result was people working side by side to break down stereotypes around mental illness, and neighborhood-enhancing murals that continue to raise awareness.