Hesperian Health Guides

Why knowing is good for a child

HealthWiki > Helping Children Live with HIV > Chapter 5: Talking with children about HIV > Why knowing is good for a child

Children who know they are HIV-positive are usually healthier and take better care of themselves as they grow older than children who do not know about their HIV. Children who understand a little about their HIV are often more willing to eat healthy food and take medications every day.

Children who know about a parent’s HIV, or that someone else they are close to has HIV, understand why that person might need more food or is sometimes tired or ill. And they may be able to learn ways to help, such as reminding the person to take their medicine.

Children can usually tell if something is wrong in their family, and will worry about what it is. Children who are not told about HIV will search for other reasons why someone is ill or gone, and they may blame themselves. Children who learn their HIV status (or that of a family member) from a sibling or neighbor often do not get the full information and support they need. Worry and other feelings can affect a child’s relationships with friends and family, and cause him to behave badly or get into trouble.

A child who understands HIV also may protect herself better from infection later on when she is exposed to sex or other ways HIV spreads.

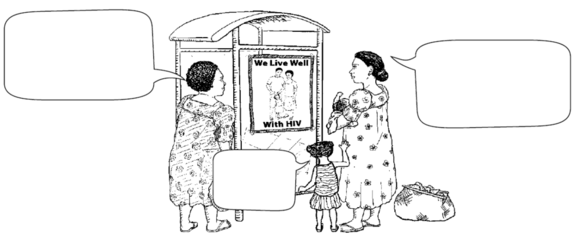

Talking with all children about HIV is important for fighting stigma, especially in communities where there is a lot of HIV. You may need to explain how illness can happen to anyone, or why it is wrong to blame people or avoid them because they are sick.

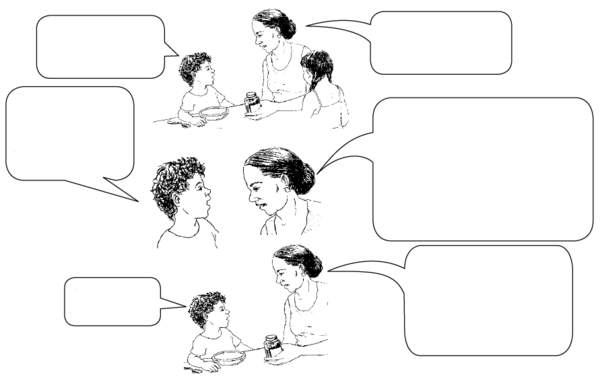

Children do not learn about HIV all at once, especially small children who cannot fully understand HIV. You may feel so afraid of disclosing your HIV status — or your child’s — to her that you wait too long to do it. It is better to think of disclosure as many conversations that happen over a period of time. At first, explain as much as your child is able to understand. As she grows, learns, and matures, you can tell her more.

Contents

Teaching a child from birth to 3 years old about HIV

Babies and small children cannot understand HIV, illness or death. But there are ways you can begin to make your home a safe place to talk about HIV, even for small children.

- Talk about medicines and be open about illness in the home. This can make taking medicine a normal part of life for children, even if they cannot understand what medicine does.

- Take your baby with you to the clinic and to community events about HIV.

Teaching a child from 3 to 5 years old about HIV

Children this age cannot understand HIV, but they can begin to understand illness. You can talk with them about avoiding germs and illness as you teach them to wash their hands before eating and after using the toilet.

Starting at about 4 years old, children can compare things that are different. They notice if they or someone in their family goes to the clinic more often than other people. They may wonder why they take medicine and others do not.

Young children can be told they (or others) have an illness, without saying it is HIV or explaining much more. Caregivers and health workers usually do not tell a child he has HIV until he is older and can understand better, including how and why to keep information private.

Teaching a child from 5 to 8 years old about HIV

Children this age are able to understand more about illness, death, and how our bodies work. They most likely have heard about HIV and AIDS, and perhaps ART, or medicine that people with HIV take every day.

When you teach children about HIV, tell them the truth about the virus and how it is spread, in simple ways they can understand. This level of understanding can help them protect and care for themselves and be more willing to take medicines.

Sometimes children this age who are HIV positive are not yet told they have HIV by name, but rather that they have a sickness in their blood. They may have seen or experienced stigma and can understand why HIV is often kept private.

Children this age can learn that you do not get HIV from hugs, bad luck, sharing food or toilets, being near someone with HIV, or witchcraft. Growing up in a home where HIV and medicine are a normal part of everyday life makes this easier.

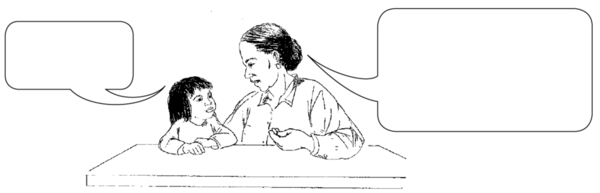

| A little germ |

Yesterday you asked me how long you must take medicine.

Yes, Mama?

I want to tell you more about why your medicine is so important.

You have something in your blood that can make you weak and ill if you do not take your medicine. It is a little germ and it weakens and tries to destroy the part of our blood that protects us from illness. Everyone has protectors in their blood. The protectors fight any germs that get inside you. This is how we stay healthy. Most people have lots of these protectors inside them. But you and I have this little germ that harms our protectors. Our medicine makes this little germ go to sleep. But it cannot ged rid of the germ completely. So we must take our medicine every day. When we do, we have many strong protectors in our blood. What do you think about that?

Aunt Salima and your teacher know about this too, so you can talk to them about it. But other people do not understand about this germ in our blood. So it’s better to speak only to Salima, Teacher Tang, or me about your medicine. OK? |

As children get older and start school, keep talking to them about HIV, about how it does and does not spread, how to stay healthy, and about the harm of stigma and what children can do to fight against it.

See Chapter 1 for more basic information about HIV, and Why stigma against people with HIV is so dangerous and Talking about stigma and privacy for more about stigma.

Teaching older children about HIV

As your child matures, you can explain more about how HIV affects the person who has it, how someone with HIV can stay healthy, how HIV spreads through sex, and how people can protect others from becoming infected.

Talking about HIV can be difficult, and talking with young people about sex can be even more difficult. If you have a strong and honest relationship with your child, these conversations will be easier. One way to have conversations with children is to read stories or news articles together, listen to the radio, or watch videos that talk about HIV. Personal stories about living with HIV or struggling to disclose to someone else are engaging and offer a lot to discuss.

In the past, another family member, such as an uncle or aunt, was often responsible for discussing sex with a young relative. This is not common now, though asking a counselor or health worker to talk with your child may help her. Young people need to prepare for the challenges they will face as young adults living with HIV, such as learning to care for themselves at school, pressure to have sex, and fear of rejection from friends and teachers.

When talking to a child or young person about sex, it is important to be honest, even if you are uncomfortable. If you speak untruthfully, and the child eventually learns the truth, they may not trust what you say to them in the future. Young people need accurate information about sex, relationships, and their health if they are to become healthy and responsible adults. You may feel it is important for them to wait before having sex. If so, try to explain why in ways they will understand.

If you do not know an answer to one of your child’s questions, tell him that you do not know. It is OK to ask for help from a nurse or someone at the clinic.

Let your child ask whatever questions he may have. Try to not react with embarrassment, judgment, or anger. If your conversation is difficult, you can suggest another adult they can talk to about sex.

Support older children to become more independent. Explain their medications and help them be responsible for taking their pills. Children ages 13 to 18 go through many intense changes and often need help developing systems to remember to take daily medicines.

Encourage young people to talk with their health worker about their medicines or lab tests so they can learn how to take care of themselves.

You may need to help your child decide whether to tell a friend or teacher about her HIV status. Help her think about if this person needs to know, and if the person is trustworthy. Discuss what might happen if the person tells others. Your child needs to learn to make these decisions on her own, and you can help her by having her think through the steps of making a decision.