Hesperian Health Guides

Evaluating Which Deformities Should Be Corrected and Which Should Not

HealthWiki > Disabled Village Children > Chapter 56: Making Sure Aids and Procedures Do More Good Than Harm > Evaluating Which Deformities Should Be Corrected and Which Should Not

PART 3 of this book, in addition to aids and equipment, also discusses methods for correcting joint contractures, which are discussed in Chapter 59. Just as you need to decide if a brace is appropriate, you need to decide whether correcting a contracture will actually help a child. Although many contractures increase difficulty for a child, some may actually help and should be left uncorrected. For example:

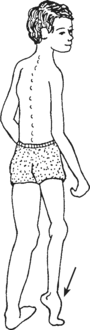

In a child with polio, the weaker leg is often shorter.

The foot hangs down and often develops a tiptoe contracture which, in effect, makes the leg longer. |

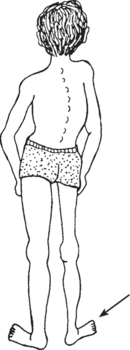

If we correct the foot contracture, the leg will, in effect, become “shorter.” This can cause tilting of the hips, a spinal curve, and more awkward walking.

contracture corrected |

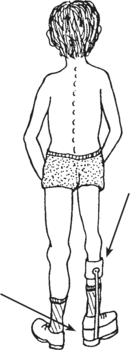

To correct the hip tilt and spinal curve, the child will need a lift on the shoe, and probably a brace too.

This usually makes walking more difficult, and the disability more noticeable, than before the contracture was corrected. |

Other examples of contractures that are sometimes more beneficial than harmful are finger contractures in persons with hand paralysis and tightness of back muscles in persons with spinal cord injury or muscular dystrophy.

Before deciding to correct any contractures or deformities, try to be sure that the correction will help the child to do things better.