Hesperian Health Guides

Chapter 52: Love, Sex, and Social Adjustment

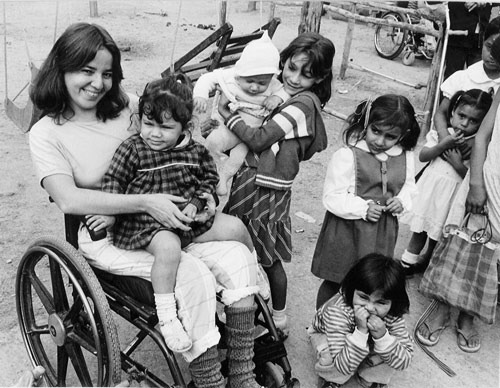

All this is fairly much accepted as “natural” and “normal” and “right” by most of the local villagers.

But things were not always this way. A few years ago, when PROJIMO had just begun, many people believed that a person with severe or even moderate disabilites should not and could not have a loving relationship, get married, or have children.

One evening in the spring, some years ago, an old woman watched a group of young couples listening to guitar players at the village square. One young man, who had a clubbed foot and used a cane, stood close to a young woman in a wheelchair. When the musicians started playing a romantic song, the couple gently put their arms around each other. The old woman was shocked. Angrily she pointed to the pair and cried, “Isn’t that disgusting! People like that have no right to behave like that! It’s not natural! They’re cripples!”

When PROJIMO first began, unfortunately the villagers were not the only ones who thought that people with disabilities should and could not get married or have loving relationships. Many young people with disabilities half-believed it themselves, and in their personal lives were often depressed, frustrated, or confused. While society told them one thing, their hearts and their bodies told them another. Most believed they could never be attractive to another person in a sexual way. Yet through adolescence, they felt increasingly attracted. Many had serious doubts about their own sexual ability. Some had discovered that they did, in fact, have fully developed feelings and functions. But they had no acceptable way to express them.

Some visiting advisers to PROJIMO were older people with disabilities who had learned to understand their own feelings and had formed loving relationships. Slowly, the young people at PROJIMO began to accept their own desires, needs, and dreams. More important, they began to discover they were not so alone, not as different from other people, as they had thought. Above all, they discovered that they were attractive to other persons. Soon the romances began.

At first, things sometimes got out of hand. The bottled-up feelings of the young people came flooding out. There were occasional mistakes and abuses. When the young people with disabilities discovered that the rules society had set for them were unfair, often their first response was to break the rules recklessly. But then, faced by the sometimes cruel results of their own hurry, passion, and inexperience, they discovered the need for a few precautions and guidelines determined by the group. They had been hurt often enough themselves not to want to cause additional hurt. And now with the spread of HIV, they are also aware they must have “safer sex” if and when they have sex.

Little by little, the PROJIMO team members have discovered their ability to live fuller lives and have more complete relationships than they had previously believed possible. Also, little by little, the local community has begun to accept this. For the first time, romances have begun to develop openly between villagers with and without disabilities. A new level of awareness and acceptance is slowly being achieved.

The personal and sexual needs of young persons

Every child has the same basic needs for food, protection, and love. The child who is treated consistently with love, respect, and understanding has a greater chance of becoming a loving, respectful, and understanding adult.

Every child has a need to be touched and held. Small children learn about themselves by exploring and touching different parts of their bodies. A child whose disability makes touching and exploring her body more difficult may have an even greater need than other children to be held and hugged.

Most societies have rules and taboos that attempt to limit and govern sexual behavior. And within most societies, young people (and old) usually find ways of getting around some of those rules, usually more or less secretly. The best answer to sex education is to talk openly and honestly about sexual themes, but also to look for informal and unsupervised ways for adolescents with disabilities to spend time with and share the “secrets” of other adolescents.

But it is also important to make sure that children with disabilities understand how to resist sexual abuse. Adults can take advantage of their power and trust and enter into sexual relations with children, especially children with disabilities. It should be explained to children that these kinds of “secrets” are not acceptable and that they should let others know about what is happening. See Helping Children Who Are Blind (Chapter 12) or Helping Children Who Are Deaf (Chapter 13) for ideas on how to prevent sexual abuse and ways to talk with children about this difficult topic.