Hesperian Health Guides

A Story to be used with the CHILD-to-child activity, "Understanding Children with Disabilities"

HealthWiki > Disabled Village Children > Chapter 47: Helping Teachers and Children > A Story to be Used with the CHILD-to-child Activity, "Understanding Children with Disabilities"

HOW TOMÁS AND OTHER CHILDREN HELPED JULIA GO TO SCHOOL

At age 7 Julia’s world was so small that you could throw a stone clear across it. She had seen almost nothing of her own village. No one ever took her anywhere. The farthest she had ever crawled was to the bushes just outside the small hut where she lived with her family.

Julia was the oldest of 3 children. Her family’s hut was at the far edge of Bella Village. The hut was separated from the main footpath by a long, steep, rocky trail. Perhaps for this reason, Julia had missed being vaccinated in her first year of life, when health workers had come to the village.

In the beginning, Julia had been a healthy baby, and quick. At 10 months of age she was already able to stand alone for a few seconds, and to say a few words, like ‘mama’, ‘papa’, and ‘wawa’—which meant water. Her face would light up in a big smile whenever anyone called her name. Her parents took great pride in her, and spoiled her terribly.

But at 10 months Julia got sick. It began like a bad cold, with fever and diarrhea. Julia’s mother took her to a doctor in a neighboring town. The doctor gave her an injection in her left backside. A few days later Julia got worse. First her left leg began to hurt her, then her back, and finally both arms and legs. Soon her whole body became very weak. She could not move her left leg at all and the other leg only a little. In a few days the fever and pain went away, but the weakness stayed, especially in her legs. The doctor in town said it was polio, and that her legs would be weak all her life.

Julia’s mother and father were very sad. In those days there was no rehabilitation worker in the village or in the neighboring towns. So Julia’s mother and father took care of her as best they could. In time, Julia learned to crawl. But she did not learn to dress or do much for herself. Her parents felt sorry for her, so they did everything for her. She gave them a lot of work.

Then, when Julia was 3 years old, a baby brother was born. This meant her parents had less time for Julia. Her little brother was a strong, happy baby, and her parents seemed to put all their hopes into the new child. They paid less attention to Julia, rarely played with her, and never took her out with them into the village. Julia had no friends or playmates —except for her baby brother. Yet sometimes, for no clear reason, Julia would pinch her baby brother and make him cry. Because of this, her parents did not let Julia hold or play with him often.

Julia became more and more quiet and unhappy. Remembering how quick and friendly she had been as a baby, her parents sometimes wondered if her mind, too, had been injured by her illness. Although the doctor had explained that polio weakens only muscles, and never affects a child’s mind, they still had their doubts.

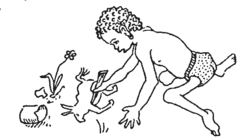

When Julia was 6 years old, a third child was born—a baby sister. This seemed to make Julia even more unhappy. She spent most of her time sitting outside behind the hut drawing pictures in the dirt with a broken stick. She drew chickens, donkeys, trees, and flowers. She drew houses, people, waterjugs, and devils with horns and long tails. Actually, she drew remarkably well for a child her age. But no one noticed her drawings. Her mother was busier than ever with the new baby.

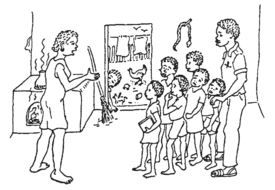

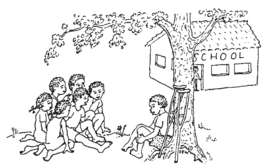

Julia was 7 years old when the village school teachers, guided by a health worker from a nearby village, began a CHILD-to-child program in the school. The first and second year children (who were in the same class) studied an activity sheet called “Understanding children with disabilities.”

Most of the children knew of only one child in their village with severe disabilities. This was Tomás. Tomás walked in a jerky way, with crutches. He had one hand that sometimes made strange movements. And he had difficulty speaking clearly, especially when he was excited. But Tomás did not seem to need any special help—or at least not anymore. He was already in the fourth grade of school and doing well. He had lots of friends. He managed to go anywhere and do almost anything for himself, if awkwardly, and nearly everyone treated him with respect.

Then one little boy remembered, “There’s a girl who lives in a house at the far end of the village. She crawls around on her hands and knees, and spends a lot of time just sitting outside. She always looks sad. I don’t know her name, but she looks old enough to be in school!”

“Let’s invite her to come to school with us,” said one of the children.

“But how,” asked another, “if she can’t walk?”

“We could bring her in a push cart!”

“No! The path from her home is too steep and rocky.”

“Then we’ll carry her! If we all help, it will be easy.’’

“Let’s go to her house this afternoon” “Good idea!”

That afternoon after school, 6 of the school children, together with their teacher, visited Julia’s home. Julia, who was out back, was too shy to come in. So they started talking with her mother.

“We want to be her friends,” they said. “And to help her go to school.”

“But she can’t go to school.” her mother said with surprise. “She can’t even walk!”

“We can carry her,” offered the children. “We’ll come for her every day and bring her back in the afternoons. It’s not far, really!”

“The whole class is ready to help out,” said the teacher. “And so am I.”

“But you don’t understand,” said her mother. “Julia’s not like other children. They’ll tease her. She is so shy she doesn’t open her mouth around strangers. And besides, I don’t see how school could help her”

The teacher tried his best to explain to the mother the great importance of school for a child like Julia. The children promised that they would all be friendly and help her in any way they could. But her mother just shook her head

“Do you think Julia would like to go to school?” asked the teacher.

Her mother gave a tired sigh. Then she turned to Julia, who was hiding outside the door but peeping in at the visitors. “Julia, darling, do you want to go to school?”

Julia’s eyes opened wide with fear. She shook her head in a terrified NO and disappeared behind the doorway.

“There, you see!” said Julia’s mother. “For Julia, school just wouldn’t make sense... Now I have a lot of work to do, please excuse me. But thank you for thinking of my poor little girl.”

“Please give it more thought,” said the teacher as he and the children went out the door. “And thank you for your time.”

“Have a nice day,” said Julia’s mother, and went back to work.

At school the next day the teacher met with the whole class to discuss their visit to Julia’s home.

“This CHILD-to-child stuff sounds so easy and fun when we pretend,” said one of the children. “But when we try to use it in real life, it ain’t so easy.”

“Isn’t!” said the teacher.

“Still,” said one little girl who had visited Julia’s home, “we have to keep trying. Did you see the way Julia looked at us? She was so scared she was shaking. But she was interested, too. I could tell. She looked so... lonely!”

“But what can we do? I don’t think her mother wants us to come back.’’

There was a long silence. Then one little boy said, “I’ve got an idea! Let’s talk to Tomás. He has a disability, too. But he’s in school and is doing fine. Maybe he can help us.”

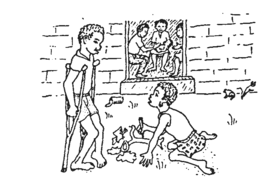

After school, several of the first and second year students waited for Tomás, who was in the fourth year. They told him about Julia, and what happened when they visited her home.

“How was it when you began school, Tomás?” asked the children. “Were you afraid? Did your parents want you to go? How did the other children treat you?”

Tomás laughed. “One question at a time!” He spoke slowly, with a twisted mouth and a sort of jerky speech that sometimes made him hard to understand. “Help me sit down under that tree.” Tomás moved forward on his crutches. The children helped him sit down. (He explained that his hips and legs wanted to stay straight when he wanted to bend them.) He sat leaning against the tree, and began to answer the children’s questions.

“Sure, I was afraid to go to school, at first,” said Tomás. “And my mom and dad didn’t want to send me. They were afraid kids would tease me or that it would be too hard for me. It was grandma who talked us all into it. She said if I couldn’t earn my living behind a plow, I’d better learn to earn it using my head. And I intend to.”

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” asked one boy.

“Maybe a health worker,” said Tomás. “I want to help other people.”

“Did other kids tease you when you started school?” asked the children.

Tomás frowned. “No ... not much. But they didn’t know what to do with me, so usually they didn’t do anything. They would stare when they thought I wasn’t looking. And they would imitate the way I talk when they thought I wasn’t listening. But when they thought I was looking and listening, they would pretend I wasn’t there. That’s what was hardest for me. They never asked me what I thought, or what I could do, or if I wanted to play with them. I felt lonelier when I was with the other children than when I was by myself!”

“But now you have lots of friends. You seem like one of the gang. What happened?”

“I don’t know,” answered Tomás. “The other kids just got used to me, I guess. They began to see that even though I walk and talk funny, I’m not really all that different from them. I think it helps that I do well in school. I like to read. I read everything I can find. Sometimes when kids in my class have trouble reading or understanding something, I help them. I like to do that. At first they gave me the nickname ‘Crabfoot’ because of how I walk. But now they call me ‘Professor’ because I help them with their lessons.”

“The first nickname was about what’s wrong with you,” observed one little girl. “And the second is about what’s right. I guess you showed them what’s most important!”

Tomás’ mouth twisted into a smile and his legs jerked with pleasure. “Tell me more about Julia,” he said.

They told him all they could, and finished by saying, “We tried as hard as we could, but Julia’s mother doesn’t want her in school and Julia doesn’t want to go either. We don’t know what to do. Do you have any ideas, Tomás?”

“Maybe if I visit the family—with my parents. They can try to convince her parents, and I’ll try to make friends with Julia.”

The next Sunday, when Tomás’ father was not working in the fields, Tomás asked his parents to go with him to Julia’s home. They arrived in the early afternoon. Julia’s mother and father, together with the 2 younger children, were all sitting in the shade in front of the hut. Julia’s father was sharpening an ax while her mother picked lice from the children’s hair. They all looked up in surprise to see the boy on crutches approaching, followed by 2 adults.

The path near the hut was steep and rocky. A few meters from the hut, Tomás tripped and fell. Julia’s father ran forward to help.

“Are you hurt?” asked Julia’s father, helping him up.

“Oh no,” laughed Tomás. “I’m used to falling. I’ve learned to do it without hurting myself... We’ve come to talk to you about Julia. These are my parents.”

“Come in,” said Julia’s father. They all exchanged greetings, and everyone went inside.

While Tomás’ parents were talking with Julia’s, Tomás asked if he could speak with Julia.

“She’s outside,” nodded her mother, pointing to the back doorway. “But she doesn’t speak to strangers. She’s too afraid!”

“She doesn’t have to speak if she doesn’t want to,” said Tomás gently, yet loudly enough so that Julia could hear, if she was listening.

Tomás went out and found Julia bent over a drawing in the dirt. She glanced up at him as he approached, and then looked down at her drawing, but without continuing it.

There were several drawings on the ground of different animals, flowers, people, and monsters. Julia had just been drawing a tree with a big nest in it and some birds.

“Did you draw all these?” asked Tomás. Julia did not answer. Her small body was trembling.

“You draw very well!” said Tomás, admiring and commenting on each of her drawings. “And with just a stick. Have you ever tried drawing with pencil and paper?” No answer. Tomás continued. “I bet that nobody in school can draw this well!” Julia, still staring at the dirt, trembled and said nothing. Tomás also was silent for a moment. Then he said. “I wish I could draw like you do. Who taught you?”

Julia slowly lifted her head up and looked at Tomás, or at least at his lower half. She looked first at his turned-in feet and the tips of his crutches. Then she looked at his knees, which had dark calluses on their inner sides where they rubbed together when he walked.

“Why do you walk with those sticks?” she asked.

“It’s the only way I can,” he said. “My legs don’t like to do what I tell them.”

Julia lifted her head and looked up into Tomás’ face. Tomás tried to smile, but knew his mouth was twisting strangely to one side.

“And why do you talk funny?” asked Julia.

“Because my mouth and lips don’t always do what I want either,” said Tomás. And it seemed he had even more trouble speaking clearly than usual.

Julia stared at him. “Do you really like my drawing?”

“I do,” said Tomás, glad to change the subject. “You have a real gift. Real talent. You should study art. I’ll bet some day you could be a great artist.”

“No,” said Julia, shaking her head. “I’ll never be anything. I can’t even walk. Look!” She pointed to her small floppy legs. “They’re even worse than yours!”

“But you draw with your hands, not your feet!” exclaimed Tomás.

Julia laughed. “You’re funny!” she said. “What’s your name?”

“Tomás.”

“Mine’s Julia. Do you really think I could be an artist? No, you’re only joking. I’ll never be anything. Everybody knows that!”

“But I’m not joking, Julia,” said Tomás. “I read in a magazine about an artist who paints birds. People come from all over the world to buy his pictures. And you know something, Julia, his arms and legs are completely paralyzed. He paints holding the brush in his mouth!”

“How does he get around?” asked Julia.

“I don’t know,” said Tomás. “People help him, I guess. But he does get around. The magazine said he has been to several countries!’

Julia said, “Wow! Do you really think I could become an artist?”

Tomás looked again at the drawings in the dirt—and truly wished he could draw as well. “I know you could!” he answered.

“How do I start?” asked Julia, sitting up eagerly.

“First,” said Tomás, “you should probably go to school!”

“But how?” said Julia, looking at her legs.

“That’s easy,” said Tomás. “All the school children want to help. But you have to want to go.”

“I... I’m afraid...” said Julia. “Do you go to school, Tomás?”

“Yes, of course,” he answered.

“Then I want to go, too!”

Inside the house, Tomás’ parents were trying to convince Julia’s parents of the importance of sending her to school. They explained how they had had the same doubts about Tomás, and how much school had helped him.

“It’s not only what he is learning that’s important,” said Tomás’ mother, “but what it has done for him personally. He has more confidence—a whole new view of himself!”

“And we’ve come to look at him differently, too,” said Tomás father. “He’s a good student—one of the leaders in his class!”

Julia’s father coughed. “Even if all you say is true, Julia doesn’t want to go. She’s afraid. You see, the same illness affected her...”

His sentence was cut off by Julia, who came bursting in the back doorway on hands and knees. “Mama! Papa!” she shouted. “Can I go to school? Will you let me? Pleeeease?”

Her father’s mouth fell open for a moment. And then he smiled.

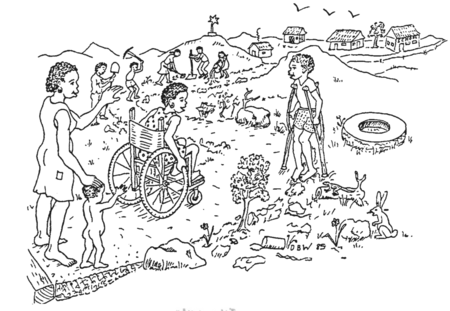

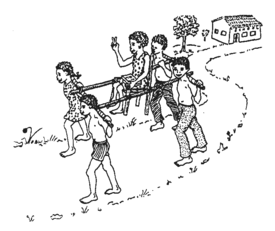

The next day Julia began school. The other children learned from Tomás that Julia was ready to go, and they worked hard Sunday evening making a ‘sitting stretcher’ for her. One of the children had seen a similar stretcher when an injured man had been carried down from the high mountains. It was a simple wooden chair, tied firmly between two poles. The children finished making it by sunset and the next morning arrived with it at Julia’s house. Tomás went with them to give Julia courage. He was so excited that he fell 3 times!

Julia was so frightened when she saw the children that she almost decided not to go. But when they brought her special chair to the door, she lifted herself onto it with her strong arms. And before she knew it, she was on her way—to school!

The first day of school went well. Everything was so new, and the children were all so friendly, that Julia almost forgot she was afraid. On the way home, she smiled and laughed as the children carried her.

Six months have now passed since Julia started school. Although she began 2 months late, she is already able to read and write letters and words as well as most of her classmates. But drawing is what she likes most. The other children often ask her to draw pictures for them.

Julia has made many friends. The children in her class who first looked at her as someone “special,” have now accepted her as one of their group. They include her in many games and activities, and treat her as just another child.

Some problems have arisen. At first, carrying Julia to and from school each day was fun. But after awhile, many of the children got lazy and stopped helping. This meant more work for those who were left.

The children got a new idea and asked their fathers for help. One Sunday a group of about 15 men and 20 children worked on improving the steep path from Julia’s house to the main walkway leading to school. They made the curves wider so that the trail would be less steep, removed all rocks, leveled the surface, and pounded the dirt into a hard, smooth surface.

One of the children’s father had a small repair shop in the village. Another was a carpenter. With the help of their children, these 2 craftsmen made a simple wheelchair out of an old chair, 2 casters, and some bicycle wheels.

Julia was excited when she saw the wheelchair. Her arms and hands were already strong, and with a little practice she learned to wheel her new chair up the long winding trail to the village.

“Now you can come and go to school on your own.” said Tomás. “How do you feel?”

“Free!” laughed Julia. “I feel like writing a declaration of independence!” Then she thought a moment and frowned. “I know I’m not completely independent—but that’s all right. We all depend on each other in some ways. And I guess that’s how it should be!”

“It’s being equal that counts,” said Tomás. “It’s knowing that you’re worth just as much as anybody else. Nobody’s perfect!”

Things also began to go better at home. As Julia’s self-respect grew, so did her parents’ appreciation of her. Suddenly both Julia and her mother realized that there were many things that Julia could do. She began to help with preparing meals, washing clothes, and taking care of her younger brother and sister. She treated them more lovingly and never pinched or made them cry (except, of course, when they deserved it!).

Julia’s mother wondered how she had ever managed to get along without Julia’s help. She missed her during the long hours she was at school. And when she realized she was going to have another baby, she thought Julia would have to stop going to school to help more at home.

Julia’s father shook his head. “No,” he said. “School is more important for Julia than for any of our other children —if she is going to learn skills to make something of her life. And besides,” he reminded his wife, “if we hadn’t sent her to school, she would probably still be sitting outside in the dirt. It took the schoolchildren to teach us what a wonderful little girl we have.”

Julia’s mother smiled and nodded in agreement. “You’re absolutely right,” she said. “The schoolchildren... and especially that wise little boy, Tomás!”