Hesperian Health Guides

Sustainable Use of Forests

HealthWiki > A Community Guide to Environmental Health > Chapter 10: Forests > Sustainable Use of Forests

Sustainable forest management means using and caring for forests in ways that meet daily needs while protecting the forests for the future. Sustainable methods are not the same everywhere. Each community needs to find what works best for them and for their forest.

Making a sustainable forest management plan helps a community decide how best to use their forest. It can also help resist threats to the forest by industry or the government. Sometimes, you can get a better price for forest products if you can show they were produced sustainably. But the most important part of a sustainable forest management plan is that it helps local people work together to use and protect forests.

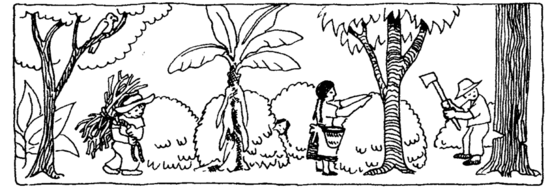

Some ways to both use and protect the forest at the same time include:

- Thinning vines, plants, and trees allows more sunlight into the forest, so that the plants you want can grow.

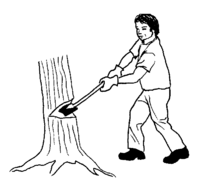

Thinning trees means cutting certain trees so the ones that remain grow wider and healthier. - Enrichment planting means planting new trees or plants under older trees or in small clearings when they do not grow back by themselves.

- Replanting after cutting is a way to make sure there will be new trees and seeds to replace the ones that were cut.

- Controlled burning can reduce brush that grows under trees. This releases nutrients into the soil, and kills pests that might hurt the trees. Controlled burns need careful planning because fires can easily burn out of control.

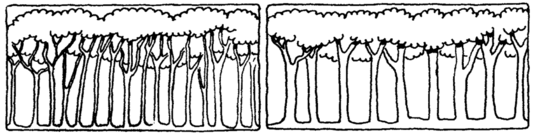

- Selective logging means cutting only some trees, while saving young trees and some healthy older trees to hold soil and provide seed for the future.

Selective logging protects some trees for the future, allowing forests to continue growing.

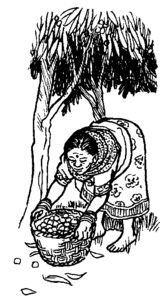

- Collecting and selling non-timber forest products rather than selling wood

is a way to care for the forest while also earning money.

- Paying ranchers to keep grazing animals out of the forest, and paying farmers not to cut trees on part of their land, can support healthy forests and prevent conflicts.

- Preserving wildlife corridors (areas of connected forest or wild land) lets wildlife live in and travel through an area.

- Planting green spaces, smaller areas of trees in places where most trees have been cut down, or where the forest is completely gone, is a way to improve the soil, water, and air even in populated cities and towns.

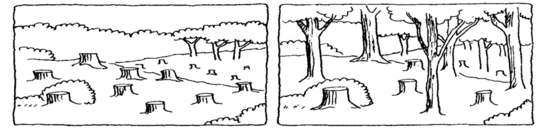

- Supporting natural regrowth of forests by limiting the use of areas where too many trees have been cut helps forests recover.

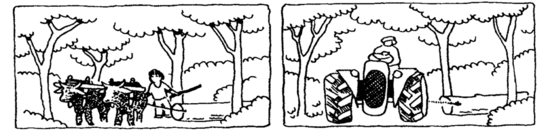

- Using animals to haul logs causes less damage than bulldozers or other heavy machinery.

Animals compact forest soil less than machines.

- Trimming bark and branches from fallen trees before taking them out of the forest causes less damage to other plants when the tree is hauled out. The bark and branches rot and make good soil.

- Ecotourism earns money by showing visitors the natural beauty of a forest, without having to cut trees or damage the environment.

There are many ways to use forests that keep them healthy for the future. Contents

Use everyone’s knowledge, consider everyone’s needs

This activity helps a community consider how to use and care for forest resources in ways that benefit everyone. It can be done with up to 25 people, divided into 3 smaller groups. It is important to include everyone who will be affected by decisions about forest use.

Time: 3 to 6 hours (or in more than one session, as long as you save the maps)

Materials: Pens, pencils, notebook paper, 3 big pieces of paper with maps of your area, and sticky tape. The maps can be roughly drawn, as long as people can recognize what they intend to show.

- Give 1 map to each group. Ask every person to draw pictures of what they do in the forest (cut firewood, graze cattle, gather fruit and plants, hunt, etc.) on their notebook papers.

- Within each group, every person talks about what they drew and what it means to them. 1 or 2 people then draw pictures on the big map to show where and how each person uses the forest.

- Bring the groups together for a discussion about what their big maps show. Are some parts of the forest used more than others? Do men, women, children and older people use the forest in different ways? Were there any surprises in the ways the forest is used?

- The facilitator leads a discussion about the health of the forest by asking questions like these: Does the forest provide the same resources now that it always did? Are there fewer birds, animals, and plants than there once were? Are there places where all the trees have been cut down? What happens now in those places?

- Have 1 or 2 people from each group mark their map using different colors or symbols to show places where the forest is healthy, degraded, or gone.

- Think about the different areas of forest and discuss what changes people want to see. Draw or write them on the map. Below are some

questions that can help

guide a discussion.

Make a forest management plan

After doing the activity above, consider these questions:

- What benefits and resources does the forest give us? What trees, plants and animals are used? How much is used in each season? Are there areas where these resources have grown scarce or have disappeared?

- How do we support the forest? Does the community plant trees, protect certain areas, or have other ways of making sure the forest stays healthy?

- Should some parts of the forest be protected from use? How will that affect people who use those parts of the forest?

- Should sustainable methods be practiced in some parts? What knowledge does the community have about caring for forests that can help to make these changes?

- What skills do we need to make sustainable forest management a success? If we do not have those skills, can we learn them? Will we need to rely on other organizations? How can we form strong alliances with organizations we trust to help us gain skills and knowledge?

- How can our community keep control over our forest projects? Well-organized communities that present a strong and clear message to outsiders about what they want usually receive greater benefits from sustainable forestry projects.

- How will we get our products to market? It is often more expensive to get products to national or foreign markets than to sell products locally. Local prices are lower, but the cost of selling is also lower.

- How much will our forest products be worth? If you wonder whether you are receiving a fair price for forest products, you may want to contact some fair trade organizations (see other resources on Nutrition, Food, and Farming).

- What changes will the new plan bring? Will the new management plan limit some people’s ability to use the forest? How will the community help them in return?

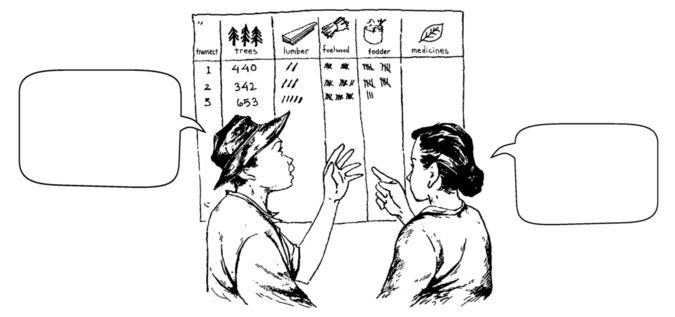

If we harvest too much wood this year, we may not have enough medicine trees next year.And we need to protect our firewood trees to last through the rainy season.

If we harvest too much wood this year, we may not have enough medicine trees next year.And we need to protect our firewood trees to last through the rainy season.Partnerships to protect the forest

Building partnerships with as many as possible of the groups that benefit from the forest helps make sure the forest is used in ways that meet everyone’s needs. Partnerships with people outside your local area can also help protect your rights.

Working together to protect the Amazon rainforest

The people of Amazanga did not always live where they do now. An oil spill forced the members of the Quichua tribe to move from their traditional land in the Amazon. When their new homes were threatened by deforestation and industrial farming, the villagers decided that managing their lands according to the traditions of their people – hunting, fishing, and gathering plants for food and medicine – was the best way to protect their lands.

But this required more land than they had. Amazanga demanded that the government grant them territory to live as their ancestors had lived. “We cannot live from a piece of land like a piece of bread,” they said. “We are talking about territory, and the right to live well from the forest.” When the government ignored their demand, they asked international environmental groups for help buying back their ancestral lands.

The villagers invited their international partners to take photographs and videotapes showing traditional ways of using the forest, and to share these with people in their home countries. After several years, Amazanga raised enough money to buy almost 2000 hectares of forest.

But buying this much land created suspicion among members of the Shuar tribe who lived nearby. When the Shuar claimed ownership of the same land, the people of Amazanga understood they had made a mistake. They had built partnerships with international organizations, but had failed to make agreements with their neighbors! The Shuar were so angry they threatened violence. After many meetings, the people of Amazanga and the Shuar agreed to share the forest according to shared rules. Because the Quichua and the Shuar have similar understandings of how to best use the forest, they were able to form an alliance.

They made the land a forest preserve and agreed to a forest management plan preventing the felling of trees and building of roads. The land was declared “patrimony of all the indigenous tribes of the Amazon” and protected for future generations. By reaching out to visitors from near and far, the people of Amazanga will protect the forest, preserve their culture, and help others to protect their own forest homes.This page was updated:05 Jan 2024