Hesperian Health Guides

Chapter 56: Making Sure Aids and Procedures Do More Good Than Harm

HealthWiki > Disabled Village Children > Chapter 56: Making Sure Aids and Procedures Do More Good Than Harm

So mostly I suffered in silence. I took the arch supports out of my shoes and hid them whenever I could. But when I was caught I was punished. I was made to feel naughty and guilty for not doing what was “best” for me.

Several years later, as my walking continued to get worse, I was prescribed a pair of metal braces. They held my ankles firmly, but they were heavy, uncomfortable, and made me feel more awkward than ever. I hated them, but wore them because I was told to.

One holiday I took a long walk in the mountains. The braces rubbed the skin on the front of my legs so badly that deep, painful sores developed. I refused to wear them again.

It was not until many years later, long after I had begun to work with children with disabilities, that a brace maker and I figured out what kind of ankle support would best meet my needs. So now I use lightweight, plastic braces that provide both the flexibility and support that best suit me.

When I look back, I realize that the doctor did not know more about what I needed than I knew. After all, I was the one who lived with my feet! True, at age 10, I could not explain the mechanics and anatomy for what was happening. But I did have a sense of what helped me manage better and what did not. Maybe if the adults who were so eager to help had included me in deciding what I needed, I might have had aids that better met my needs. And I might not have felt so guilty and naughty for expressing my opinion.

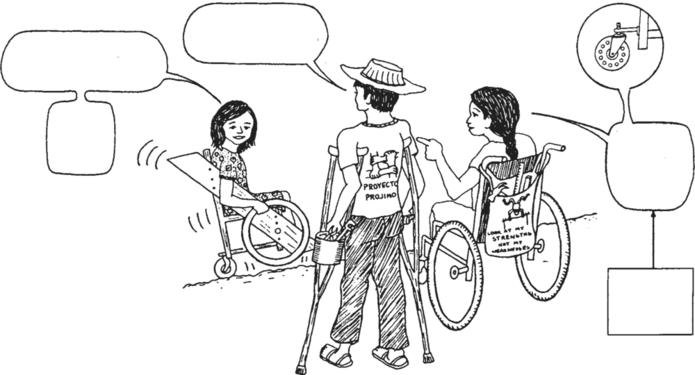

I learned something from these childhood experiences. I learned how important it is to listen to a child with disabilities, to ask the child at every stage how she feels about an aid or an exercise, and to include the child and her parents in deciding what she needs. The child and her parents may not always be right. But doctors, therapists, and rehabilitation workers are not always right either. By respecting each other’s knowledge and looking together for solutions, they can come closest to meeting the child’s needs.

Some of the best design improvements in aids and equipment come from the ideas and suggestions of the children who try them out.